| Almanac of news nishikie and related topics | |||||

| Introduction | Newspapers | News nishikie | Other nishikie | Who's who | Glossary |

Newspapers that figured in the birth, growth, and demise of news nishikie are presented here. Of particular interest are Tokyo nichinichi shinbun and Yubin hochi shinbun, which were sources of stories for many news nishikie, not only those that used their names. A few newspapers are listed only because they involved some of the drawers and writers who were instrumental in producing the most important news nishikie.

|

平仮名絵入新聞 Hiragana eiri shinbun Hiragana illustrated news |

|

|

Small-news (koshinbun) paper Started by Ochiai Yoshiiku, Takabatake Ransen, Nishida Densuke, and Okada Jisuke. First published every other day.

One issue -- 1 sen. |

|

| 1875-4-17 | First issue published. |

| 1875-9-2 | Renamed Tokyo hiragana eiri shinbun and becomes daily. |

| 1876-3-2 | Renamed Tokyo eiri shinbun. |

| 1889-3 | Ceases publication. |

|

Hiragana eiri shinbun made reading more enjoyable for the masses by featuring more illustrations. Yoshiiku did the drawings while Takabatake did the writing and editing. The paper was aimed at readers who wanted kanji with furigana and illustrations. It carried serialized stories by popular fiction writers including Takabatake. The launch of the paper has every appearance of being a decision by Yoshiiku and Takabatake to "newspaperize" the "illustrated news" idea that had been pioneered by the nishikie edition of Tokyo nichinichi shinbun. During the first few months after the launch of Hiragana eiri shinbun, Yoshiiku and Tentendo continued to crank out the Tonichi nishikie. The masthead of Tokyo eiri shinbun, as the paper finally came to be called, was modeled after the cherub-born banner of Tonichi's nishikie. This is almost certainly Yoshiiku's declaration that, as far as Japanese newspapers were concerned, this was his design. Yoshiiku was familiar with illustrated newspapers. In producing a series of woodblock prints about Yokohama in 1860, he is known to have made reference to copies of The Illustrated London News, whose first issue came out on 14 May 1842. (Newspark 2001:63,2-2) Tokyo nichinichi shinbun publicized the new paper eight times beginning with its 16 April 1875 issue. The ads stated that the paper, as its name implied, would generally use hiragana and not unfamiliar kanji expressions, and would have illustrations in every issue, for the benefit of women and children. (Tsuchiya 1975:22-24) See Morality and Censorship for a discussion of how women and children figured in the moral pretext for publishing other newspapers and news nishikie. (WW) |

|

|

警察新報 Keisatsu shinpo Police news |

|

|

Small-news (koshinbun) paper Started by Jono Denpei, Nishida Densuke, and Tatebe Kokichi. One issue -- 1 sen. |

|

| 1884-10-4 | First issue. |

| 1886-10 | Reborn as Yamato shinbun. |

| Keisatsu shinpo, like Hiragana eiri shinbun, is thought to have been started as a "small-news" (koshinbun) sister of Tokyo nichinichi shinbun, a "large-news" (oshinbun) paper. Apparently Jono, Nishida, and Tatebe remained affiliated with Nipposha, which published Tonichi. The new paper didn't last long, however, and by October 1886 its founders had revamped it into another small-news paper called Yamato shinbun. (Newspark 2001:83) (WW) | |

|

女新聞 Onna shinbun Women's news |

|

|

Small-news (koshinbun) paper |

|

Onna shinbunAt least 120 issues of Onna shinbun were published between June 1888 and mid 1890 at weekly or five-day intervals. Very little is known about the paper, which was produced by men. |

|

Onna shinbun nishikie supplementSee Kenjoden |

|

|

Published by Onna Shinbun Sha. Issues first came out about once a week and later every 5th day. |

|

| 1888-6 |

1st issue, Meiji 21-06. Publication reportedly began in June 1888. June 1888 had 4 Sundays and 6 "50 days". |

| 1888-7 | July 1888 had 5 Sundays and 6 "50 days". |

| 1888-08 | August 1888 had 4 Sundays and 6 "50 days". |

| 1888-09-23 |

15th issue, Meiji 21-09-23 (Sunday) Particulars on Kenjoden / Kesa Gozen nishikie furoku distributed with the issue. September 1888 had 5 Sundays and 6 "50 days". The 23rd fell on the 4th Sunday. |

| 1889-11-15 |

Issue 83, Meiji 22-11-15 (Friday) Data from Japan Archives image. November 1889 had 5 Sundays and 6 "50 days". |

| 1890-01-20 |

Issue 95, Meiji 23-01-20 (Monday). First of 24-issue lot offered by Nagumo Shoten NLT 2016. January 1890 had 4 Sundays and 6 "50 days". 15 Nov 1889 (Issue 83) to 20 Jan 1890 (Issue 95) spanned 14 "50 days". Issue 83 to Issue 115 spanned 13 issues (14 days - 1). Paper probably not published on 31 December 1889. |

| 1890 [5-20] |

Issue 120, Meiji 23 [05-25 (Sunday)] <Estimated>. Last of 24-issue lot offered by Nagumo Shoten NLT 2016. Lot included issues 95-116, 119, 120 (last viewed March 2019). |

|

絵入新聞 西國戦争日誌 Eiri shinbun / Saigoku senso nisshi Illustrated news / Western provinces war daily journal |

|

| See article Saigoku senso nishi: A chronicle of disturbances heralding Seinan War. |

|

新聞誌 Shinbunshi News record |

|

|

Yokohama's first Japanese-language newspaper Published by Joseph Heco with the help of Kishida Ginko and Honma Senzo. Place of publication -- Heco's residence Foreign Settlement No. 141 in Yokohama. |

|

| Genji 1-6-28 | 1864-7-31 -- First issue. |

| Genji 2-3 | Circa 1865-4 -- Changed named to Kaigai shinbun (海外新聞) [Overseas news]. |

| Keio 2-10 | Circa 1866-11 -- Discontinued publication. |

|

Shinbunshi carried general news, but also news about gold and other markets overeas, some shipping news, and advertising from shops run by foreigners. It was basically intended to promote trade and commerce in Yokohama. The paper was hand-written for the first nine months, and was printed from woodblocks after changing it was revamped as Kaigai shinbun. It was published twice a month and ran for 26 issues. Its cover featured sketches of sailing ships in Yokohama bay, Mt. Fuji, and the Port of Yokohama seen from the sky. Foreign Settlement No. 141 is now 141-banchi in Yamashitacho, Naka-ku, Yokohama. A monument has been erected on Kaiteibyo dori street in China Town in commemoration of the "Birthplace of the Japanese Newspaper" (Shinbun Hassho Kinen Hi). |

|

|

東京絵入新聞 Tokyo eiri shinbun Tokyo illustrated news |

|

| Name of Hiragana eiri shinbun from March 1876. |

|

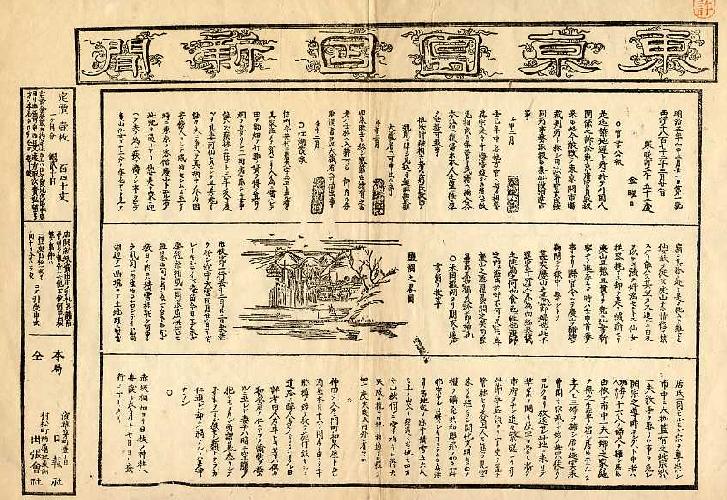

東亰日日新聞 (東亰日日) [東日] Tokyo [Tokei] nichinichi shinbun (Tokyo [Tokei] nichinichi) [Tonichi] Tokyo daily news 東京 (Tokyo, Tokei) was commonly written 東亰 (Tokei, Tokyo) until about the middle of the Meiji period. The character 東 is considered a popular alternative of 京 though careful writers would graphically differentiate them. The Sino-Japanese Go (Wu = pre-Tang), Kan (Han = Tang, Chang'an), and To (Tang = Song, Yuan, Ming, Yuan, Qing) readings of both characters were kyō (kiyou, kiyau), kei, and kin. |

|

|

Large-news (oshinbun) paper Tokyo's first daily paper Started by Jono Denpei, Ochiai Yoshiiku, Nishida Densuke, and Hirooka Kosuke. One issue -- 140 mon (of copper). |

|

| 1872-3-29 | First issue (Meiji 5 Jinshin 2-21). |

| 1874-6 | Absorbed Kankyo Tokyo nichinichi shinbun. |

| 1911-3-1 | Absorbed by Osaka mainichi shinbun but retained name. |

| 1936-12-26 | Absorbed Jiji shinpo. |

| 1943-1-1 | Renamed Mainichi shinbun / Tokyo. |

| 1951-10-1 | Absorbed Yukan mainichi shinbun. |

FoundingTokyo nichinichi shinbun was published in 1872 by Nipposha (日報社), a company founded the same year by gesaku writer Jono Denpei (1832-1902), woodblock drawer Ochiai Yoshiiku (1833-1904), lending library manager Nishida Densuke (1838-1910), and Hirooka Kosuke (1829-1918), a colleague of Nishida's. The first issue of the paper came out on the 21st day of the 2nd month of the 5th year of Meiji (29 March 1872). Tonichi continued to publish under its own name after it was bought by Osaka mainichi shinbun in 1911. Both papers were merged in 1942 and from 1943 they became Mainichi shimbun. Tokyo nichinichi shinbun seems to have been conceived during the 10th month of Meiji 4 (October or December 1871), at a lending library owned by Tsuji Den'emon. The bookstore sponsored art promtion parties [興画会 kyogakai] attended by gesaku writers, woodblock drawers, and others (Soma 1941:6, and Ono 1972:9 following Soma, have 狂画会 [kyogakai] or "mad-art parties"). Things had quieted down after the initial confusion of the restoration, and they talked about how to make money. Someone suggested starting a newspaper. Present during this conversation were Jono Denpei and Nishida Densuke, who had helped Fukuchi Gen'ichiro publish Koko shinbun in 1868, and Ochiai Yoshiiku. These three men -- and Hirooka Kosuke, another Koko shinbun veteran -- brought out the first issue of Tokyo nichinichi shinbun on the 21st day of the 2nd month of Meiji 5 (29 March 1872). The first issue was printed with two colors on one side of a sheet of mulberry washi known as minogami. It reported a few government announcements and an account of a murder. (Ono 1972:8) The gesaku writer Takabatake Ransen (1838-1885) joined Tonichi in the third month of Meiji 5 (April or May 1872). In April 1873, Yoshiiku started Hiragana eiri shinbun, Japan's first illustrated newspaper. Ransen became its editor -- then moved to Yomiuri shinbun in December. The writer Hokiyama Kageo, and the colorful journalist Kishida Ginko (1833-1905), also joined the Tonichi staff in 1873. Woodblocks to Moveable TypeThe first issue was printed on one sheet from woodblocks. The second and subsequent early issues were printed on a press using both lead and wood moveable type. An acquaitance in the neighborhood, on the advise of Kishida Ginko, had imported a moveable-type press from Shanghai, where Kishida had lived while helping Hepburn edit his dictionary. Problem was, there wasn't a lot of type, so Yoshiiku and his friends made due with what they had, throwing in kana whenever they didn't have kanji. This resulted in an "atrocious layout" (muzan-na shimen) which required careful reading to understand. (Okitsu 1997:10-11) Fukuchi Becomes Chief EditorIn 1874, Fukuda Gen'ichiro (1841-1906) resigned his post at the Ministry of Finance and joined Tonichi as its chief editor, turning down an offer from Tonichi's rival, Yubin hochi shinbun. Fukuchi was not a stranger to Tonichi's founders. They were same men who had helped him publish Koko shinbun in 1868, a venture which culminated in Fukuchi's arrest, making him the first Japanese journalist to be jailed for his thoughts and actions. Fukuchi's friendship with Jono went back much further. Living up to his reputation, Fukuchi immediately began reforming Tonichi along his lines of thinking. Its status as an official mouthpiece of the government created a bit of a problem for him. Though close to many of the most powerful people of the times, and politically ambitious, as a polemicist he believed in editorial independence. In the early 1880s, the major newspapers, most of them already supported by political patrons, began to align themsevles with one of the political parties that formed to debate issues involved in the drafting of the constitution. In 1884, Fukuchi's loyalist gradualist (conservative, go-slow) leanings moved him to affiliate Tonichi with the Constitutional Imperial Party -- Rikken Teisei To (立憲帝政党), literally "constitution-formed imperial-government party -- of which he was a leading member. Like many southwesterners (Saigo Takamori and Eto Shinpei), Fukuchi had backed the imperial restoration, and he continued to favor the idea of imperial sovereignty mediated by an elite oligarchy. Though a reformist who advocated a free press, Fukuchi also believed in safeguarding the imperial polity while wading very slowly into the uncharted waters of liberal democracy. This made him somewhat of a minority at a time when many political leaders, intellectuals, and journalists were pushing for reforms that would have weakened the principle of imperial sovereignty, and the powers of the ruling oligarchy that gained its legitimacy through the imperial system. Founders LeaveAfter Fukuchi threw Tonichi's support to the Constitutional Imperial Party, all of the paper's founders decided it was time to move on. The reasons they quit are not entirely clear. The paper was having all kinds of problems. It was losing its privileges with the government, and circulation was down. Jono, Nishida, and Yoshiiku may have felt a bit cramped by Fukuchi's style. Perhaps they just wanted some fresh air. Jono and Nishida immediately started a paper called Keisatsu shinpo (Police bulletin), which reported police news. It quickly folded, but the never-say-die Jono resuscitated the paper as Yamato shinbun, a paper of popular tastes which did quite well. Jono hired Yoshitoshi to draw illustrations for the revamped paper and produce a nishikie supplement called Kinsei Jinbutsu Shi. Jono started writing again, and some of his stories were serialized in the paper (it helps when you're the boss). Yoshiiku went into business and continued to produce a few woodblock prints. Fukuchi RetiresFukuchi himself, fed up with politics, quit Tonichi in 1888 to design and build the Kabukiza. He spent the rest of his life writing plays and fiction, translating works from English, and hanging out with old literary friends, including Jono. During 1901 and 1902, the last years of Jono's life, Fukuchi regularly contributed to Jono's Yamato shinbun. Realizing a long-cherished dream, Fukuchi was elected to the Lower House of the Diet in 1904, though the Russo-Japanese War, and his failing health, prevented him from having any impact. He died of a kidney condition in 1906. (Huffman 1980:187-188) SourcesOno 1972, Huffman 1980, and Takahashi 1992a, and Tsuchiya 1995, 2000, and 2001 all have information about Tokyo nichinichi shinbun. They vary somewhat on details but tell the same story. Okitsu 1997 includes a lot more detail on the people involved and has more vivid reconstructions of what probably transpired between them. (WW) A very brief and sketchy history of the Tokyo nichinichi shinbun from 1872 to 1943 is posted by Waseda University Library in both Japanese and English. |

|

|

やまと新聞 Yamato shinbun Yamato news |

|

|

Small-news (koshinbun) paper |

|

Yamato NewsYamato shinbun was founded in 1886 by Fukuchi Gen'ichi and Jono Denpei. Jono, who had written several stories for the Eimei nijuhasshuku and collaborated with Yoshitoshi on other works, employed Yoshitoshi as an illustrator for the paper. Yoshitoshi also drew a monthly nishikie supplement called Kinsei jinbutsu shi (Accounts of recent-age personalities). Jono's young son Ken'ichi, later the Nihonga drawer Kaburaki Kiyokata, took an interest in art from about this time. His father also put him to work as an illustrator for the paper, and he about the time of Yoshitoshi's death in 1892, Ken'ichi became a student of one of Yoshitoshi's understudies, Mizuno Toshikata. |

|

Yamato News nishikie supplement |

|

郵便報知新聞 Yubin hochi shinbun Postal dispatch news |

|

|

Large-news (oshinbun) paper First newspaper delivered through postal system Founded and edited by Konishi Gikei (小西義敬) with the backing of Maejima Hisoka (前島密 1835-1919), and published by Ōta Kin'emon (太田金右衛門). Began as a pamphlet (sasshi) of hanshiban paper which, when folded, was about 6 by 9 inches, roughly the size of a large digest, and was published five times a month. Later it became a daily. |

|

| 1872-7-15 | First issue (Meiji 5-6-10). |

| 1873 | "Hochisha" company founded. |

| 1894-12-26 | Yubin hochi shinbun became just Hochi shinbun. |

| 1942-8-5 | Joined with Yomiuri shinbun, which was renamed Yomiuri hochi, as result of wartime government-mandated newspaper mergers. |

| 1946-5 | Published as part of Yomiuri shinbun. |

| 1946-12-15 | Hochi group left Yomiuri and launched new paper called Shin Hochi. |

| 1948-9-1 | Name of paper restored to Hochi shinbun. |

| 1949 | Floundered and returned to Yomiuri fold. |

| 1949-12-30 | Reborn as Yomiuri-affiliated sports sheet called Supootsu Hochi, which today is published and distributed nationally. |

|

See Hochi early issues for further details, images, and samplings of stories. |

|

|

読売新聞 Yomiuri shinbun Yomiuri news |

|

|

Small-news (koshinbun) paper |

|

| 1874-11-2 | First issue. |

| Present | Still publishing under same name. |

Yomiuri KawarabanThe writing of kawaraban (瓦版) in kanji meaning "tile print" is deceiving and most likely reflects a folk etymology related to a place name. News sheets in Japan probably go back to the late 16th century though the earliest extant example of a so-called kawaraban is dated 1615. Such one-off sheets were not, in fact, called kawaraban until the middle of the 19th century. Moreover, a kawaraban printed from a clay block has not yet to been found. All known kawaraban have been printed from woodblocks. Until the Bakumatsu period, kawaraban were called yomiuri, denoting the fact that the news was read and sold. The Yomiuri Shinbun, Japan's highest circulating daily today, in fact originated as a kawaraban news sheet. The etymology of kawaraban is thought to be either a place in Kyoto (Kawara) where yomiuri-like stories were published, or an allusion to kawarake, an unglazed earthenware, in the sense that yomiuri news sheets were materially rather plain publications. (Nakae 2003:70) Yomiuri vendors read the newsprints aloud to sell them. Just think of a newspaper vendor who hawks papers shouts "Read all about it, read all about. Kerry tromps Bush by a landslide. Read about it. Read all about it." (WW) |

|

Yomiuri NewsForthcoming. |

|