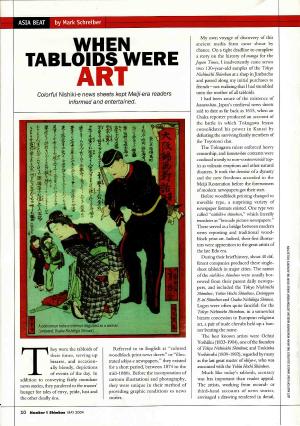

When tabloids were art

Colorful nishikie news sheetskept Meiji-era readers informed and entertained

By Mark Schreiber

An earlier version of this article appeared as part of the cover story ofNumber 1 Shimbun [Foreign Correspondents Club of Japan], May 2004, pages 10-11.

This article is posted for historical interest only, as it contains some statements which are not supported by evidence. See review of original article in Bibliography (Schreiber 2004a). For a more accurate overview of news nishikie, see "News nishikie: An arranged marriage that didn't last".

Graphic tabloidsRegarded today as art, they were the tabloids of their times, serving up bizarre, and occasionally bloody depictions of events of the day. In addition to conveying fairly mundane news stories, they pandered to the masses' hunger for tales of envy, pride, lust, and the other deadly sins. Sometimes quaintly referred to in English as "colored woodblock print newssheets" or "illustrated ukiyo-e newspapers," news-related nishikie were published for a short period, between 1874 to the mid- or late-1880s, depending on their definition. Before the incorporation of cartoon illustrations and photography, they were unique in their method of providing graphic renditions of stories in the news. This voyage of discovery, as it turned out, came about completely by chance. On a tight deadline to complete a story on the history of manga for The Japan Times, I inadvertently came across prints of two editions of the Tokyo nichinichi shinbun at a shop in Jimbocho, which I bought and passed on to friends -- not realizing that I had stumbled onto the mother of all colored tabloids. Evolving news mediaI was well aware of the existence of kawaraban woodblock news sheets dating back as far as 1615, when an Osaka reporter produced an account of the battle in which Tokugawa Ieyasu consolidated his power in Kansai by defeating the surviving family members of the Toyotomi clan. The Tokugawa rulers, however, enforced heavy censorship of most news, and subsequent kawara-ban contents were confined mostly to reports such non-controversial topics as volcanic eruptions and other natural disasters. It took the demise of a dynasty and the new freedoms accorded in the Meiji Restoration before the forerunners of modern newspapers got their start. Before woodblock printing changed to movable type, a surprising variety of news formats existed, including small booklets. One type was called nishikie shinbun, which literally translates as "colored picture newspapers". They served as a bridge between modern news reporting and traditional woodblock print art, and the men who drew them had been apprenticed to the great woodblock drawers of the late Edo era. Some 40 different news nishikie titles are known. They were producted by woodblock companies, though some the mastheads of some, like Tokyo nichinichi shinbun and Yubin hochi shinbun, derived from the newspaper affiliate from which they took their stories. Others, especially in Osaka, which did not have newspapers at the time the news nishikie began in Tokyo, had their own mastheads. The news nishikie mastheads were often quite fanciful. The masthead of Tokyo nichinichi shinbun, reflecting the influence of European art, featured a pair of nude cherubs holding up a banner bearing the name of the affiliate paper. Nishikie productionThe best known drawers of the times were Ochiai Yoshiiku (1833-1904), one of the founders of Tokyo nichinichi shinbun, and Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892), regarded by many as last great master of ukiyo-e, and famous for his graphic violence, who was associated with the Yubin hochi shinbun. The two drawers engaged in bitter rivalry. Much like in today's tabloids, accurate reporting was of less importance than the graphic appeal of the accompanying illustrations. The drawers, working from second- or third-hand accounts of news stories, envisaged a drawing that was rendered in realistic detail, often exaggerated to the point that some were quite gruesome! After sketching out a master, the design would be traced over wood panels, and then carved out onto a series of "hangi" (wood blocks) by assistants using special gouges and chisels. Each block printed a single color. The names of the illustrators and woodblock carvers appeared on each sheet. Clearly more comfortable adhering to their traditional style, the drawers depicted most subjects (whom they almost certainly never saw) clad in kimono, with males still sporting the chonmage topknot, as opposed to the zangiri (western hair style) that had gradually begun to catch on from following issuance of the Danpatsurei Edict in 1871. New aniline dyes from Europe permitted more lively colors than traditional woodblock inks. Printed on single sheets of washi, they sold for between 1.6 to 2 sen (a sen is 1/100 of a yen), half or even less the price of a regular newspaper. The larger versions tended to take portrait-style (i.e., vertical) format of nearly B4 size, whereas the smaller versions, many in landscape-style (horizontal), were closer to B5. Variety of storiesWhat sort of news did they report? In organizing some 750 examples of the genre on a CD-ROM, Dr. Reiko Tsuchiya, currently associate professor of Sociology and Media History at Osaka City University, categorizes them according to 16 different themes, such as heroic policemen apprehending thieves; touching acts of filial piety; love suicides; accounts of duels and vendettas; marital discord; crimes of passion; matters involving foreigners; and ghostly apparitions and other weird tales. These stories were usually, but not always, extrapolated from the original newspaper articles, although they occasionally reverted to traditional legendary figures and popular stories. The illustrated versions typically appeared at intervals of from several days to two months after the first newspaper appearance, and instead of carrying a date were numbered in series. Dispatches from the war between the sexes was an especially popular theme, as attested to by this particularly gruesome incident, depicted by Shigehiro in a Osaka nichinichi shimbun nishikie dated 1875.

According to Tsuchiya, news contents were not national but tended to focus on events in the region where the newssheets were sold. She believes this regularity and localization make nishiki-e shimbun, though said to have been bought as gifts, the first periodicals in Japan to present news through a visual medium. Why did such a popular medium die out so quickly? The Seinan War of 1877-78, instigated by Kagoshima's Takamori Saigo, created a hunger for accurate and timely news. While nishiki-e shimbun did enjoy a brief revival during the war, ordinary newspapers became accepted as the standard medium of obtaining news, and the genre metamorphosed into a form of entertainment. Today, its closest descendants are the tabloids and magazines with short features illustrated by scandalous photographs. |