"Minor stories" and style

The essence of "shōsetsu" and news nishikie

By William Wetherall

First drafted 24 January 2010

Last updated 11 February 2010

Stories big and small

"Minor stories" in Han times

|

Takabatake Ransen as "writer of minor stories"

Tsubouchi Shoyo

"Divine-marrow of minor-stories"

|

Romances and novels

|

Didactic versus real

|

Fiction taxonomy

Meiji writing

Bakincho

|

Gazoku setchu

|

Genbun itchi

|

Kikuchi Dairoku . . .

&

. . . Hugh Blair

|

Tomasi on Kikuchi

|

Wu on Kikuchi

Sources

Writing and rhetoric

|

Takabatake 1875

|

Tsubouchi 1885-1886

Stories big and small

Forthcoming

"Minor stories" in Han times

Forthcoming.

Takabatake Ransen as "writer of minor stories"

That Tentendō styled himself this, on this particular print, is significant because his first work of fiction, Kaika hyaku monogatari, had come out in May 1875, a month or so before the Tonichi article on which this print is based. For details, see TNS-876 Mysterious incidents.

Within a decade, by the early 1880s, the translator, writer, and critic Tsubouchi Shōyō began using the term 小説 (shōsetsu) -- which goes back to at least the Han period of China -- to translate the English word "novel" (ノベル) and explore its implications for Japanese literature. See "Minor stories" and style: The essence of "shōsetsu" and news nishikie for details.

The journalist and gesaku writer Takabatake Ransen (

Tentendō refers to himself as a writer of "minor stories" in his by-line on TNS-101, TNS-1046, and TNS 1054.

Takabatake Ransen (1838-1885), when signing one of his news nishikie As a Sino-Japanese term, "shōsetsu" was not to be equated with with the English term "novel" or its equivalents in other European languages for another decade (see Tsubouchi Shōyō (1859-1935) on "small-talk" below).

As Tentendō used the term, it most likely meant "reports about happenings and topics of conversation in town" -- as Kōjien (5th edition, 1998) digests a passage from the Yìwénzhì (藝文志) or "Bibliographic record" chapter of the Hànshū or "Book of Han" -- a history of the Early Han period (circa 206 BC to AD 25) compiled and supplemented during the Later Han period (circa 25 to 220).

The Han passage, as also cited in Kōjien, begins with the phrase 小説家者流 (xiăo shuō jiā zhĕ liú), meaning "those [who are] of the small-talk-house [school, speciality (of writing)] are flowing [spreading, popular]".

The Han expression "small-talk-practioneer" (小説家) -- also used by Tsubouchi (see below) -- is now the standard term for "novelist" or "fiction writer" in Chinese (xiăo-shuō-jiā), Korean (소설가 so-sŏl-ga,), Japanese (shō-setsu-ka), and Vietnamese (tiểu-thuyết-gia).

Tsubouchi Shoyo

Forthcoming.

Tsubouchi Yūzō (坪内逍遥 1859-1935)

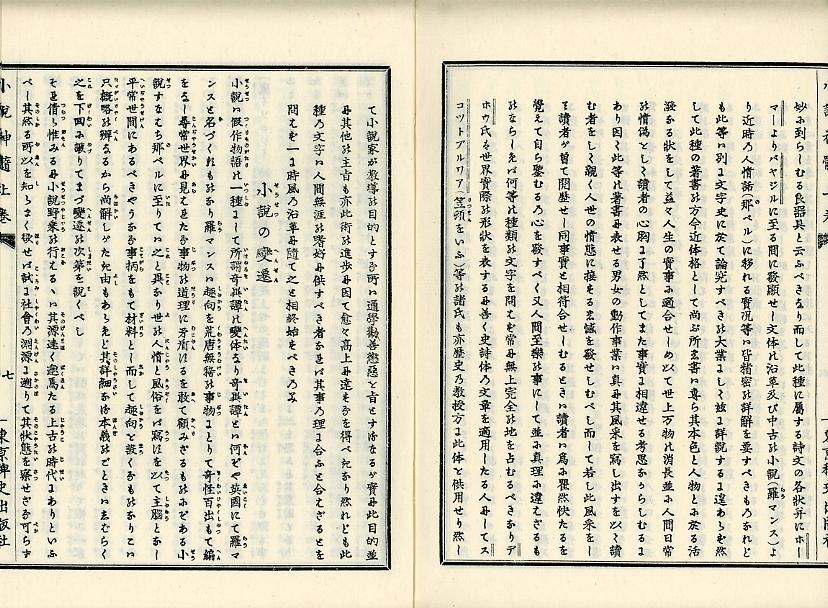

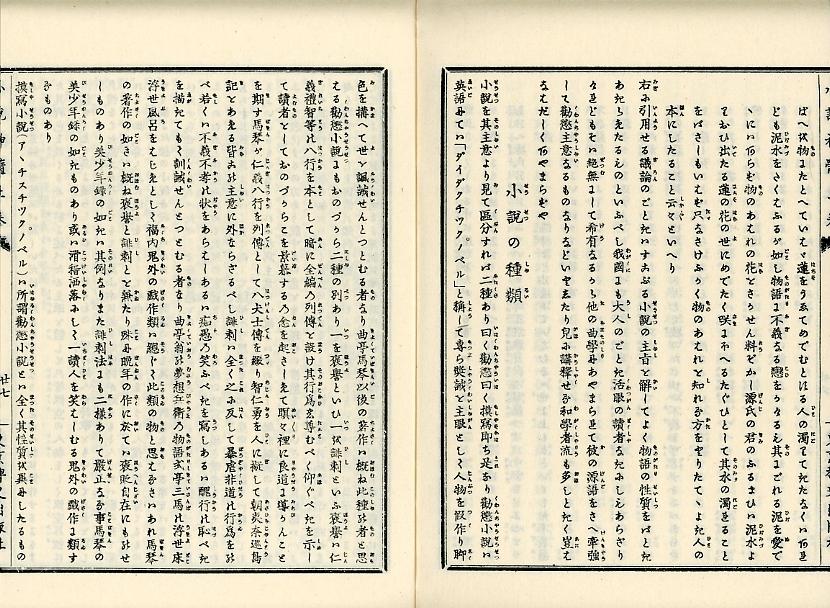

The images were scanned from the 1976 facsimile of the 1885-1886 edition.

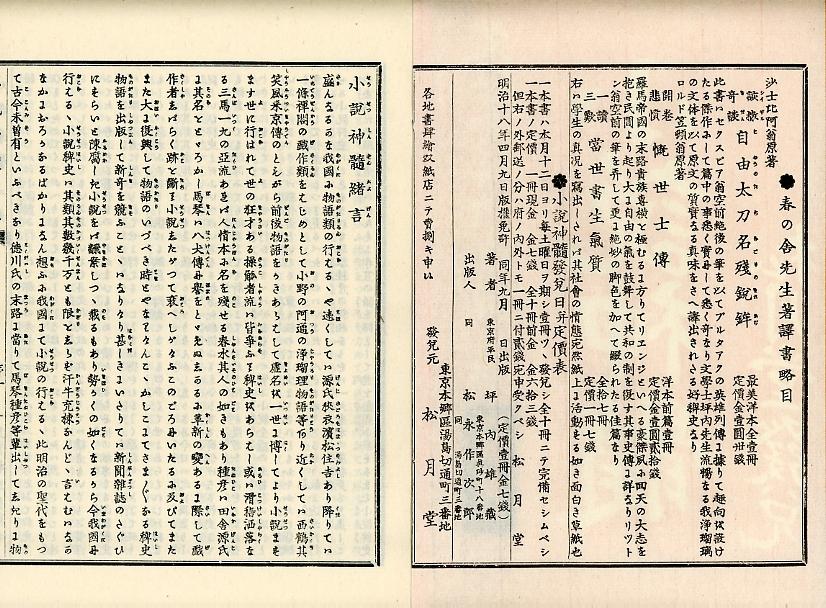

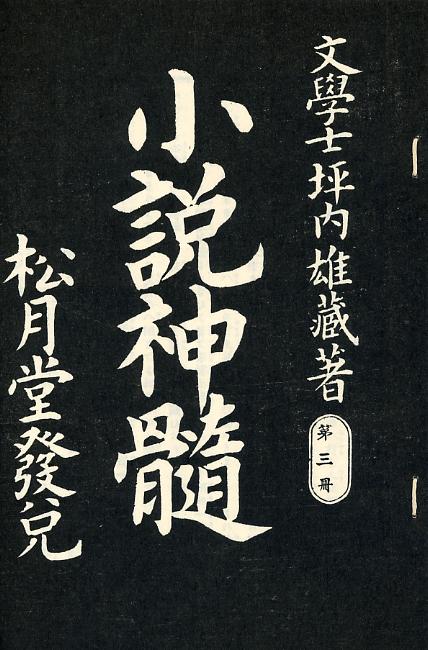

"Divine-marrow of minor-stories"

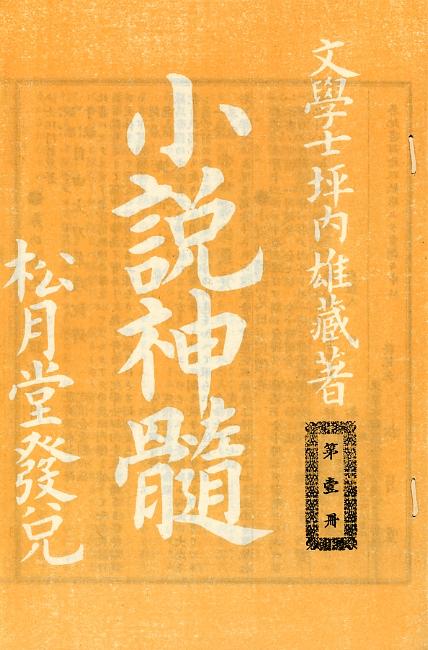

A decade after Tentendō called himself a "writer of small-talk" and shortly after Takabatake died, Shōgatsudō began publishing a pamphlet version Tsubouchi's Shōsetsu shinzui (小説神髄) or "Minor-stories divine-marrow", parts of which had appeared in various magazines and journals as early as 1883. which had began publishing the writing his famous essay . The title of the essay, published in nine booklets between September 1885 and April 1886essay was published The report

The title means "The soul of the novel" -- since Tsubouchi explicitly used "shōsetsu" (小説) to translate "novel" (ノベル noberu).

The term 神髄 appears to be inspired by the expression 精神骨髄 (seishin kotsuzui) or "spirit-deity bone-morrow", in the following phrase at the end of Chapter 1, in a long citation from a work by Kikuchi Dairoku (see below) (page 7a, see image below).

|

小説家が教導の目的とする所は通學勸善懲惡を旨とするなるが . . . 。 Where minor-story-practioners make teaching-and-guidance [instruction] their eye-target [object, aim], [they] usually make the encouragement-of-good and chastisement-of-evil [moralization] [their] intention [purpose, principle], but . . . . |

I have, of course, intentionally translated the passage very structurally, in order to show its strict parallel phrasing. A more interpretive rendering would be "Novelists, when aiming to instruct, usually resort to moralization".

The images were scanned from the 1976 facsimile of the 1885-1886 edition.

Romances and novels

Forthcoming.

|

The terms "romance" and "novel" appear in both Chapters 1 and 2 in Booklet 1 as 羅らうマンス (raumansu) and 那のベル (noberu). Elsewhere in his essay, too, Tsubouchi generally glossed 羅 as "rau", though the taxonomic chart in Chapter 4 (see below) shows "rou".

Toward the end of Chapter 1, Tsubouchi cites parts of pamphlet called 修辭及華文 (Shūji oyobi kabun) -- literally "Cultivated-speech and elegant-writing" -- meaning "Rhetoric and belles lettres" -- which he describes as a translation by Kikuchi Dairoku (菊池大麓 1855-1917). The work he refers to was published in March 1879 by the Ministry of Education.

Kikuchi, when still a boy, had gone to England to study, then returned to Japan, then gone back to England in 1870 to attend Cambridge, from which he graduated and returned to Japan in 1877. The 1879 booklet was a Japanese version of parts of Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres, a work by Hugh Blair (1718-1800), first published in 1783, the year Blair retired from his position as Chair of Rhetoric and Belles Lettres at the University of Edinburgh.

Tsubouchi introduces his last citation from Kikuchi under the heading "historical songs (epic poems)" -- 歴史歌れきしうた (委ヱピツク保ぽエム) -- rekishi-uta (wepitsuku poemu) > rekishi-uta (epikku poemu). The citation begins with the following statement (SZ-1 6a, Bunko 34).

|

時の新古を論ぜず國の東西を問はず凡そ記事の本色ハは必ず其詩史の精神骨髄たるなり Toki no shinko wo [o] ronzezu kuni no tōzai o towazu oyoso kiji no honshoku ha [wa] kanarazu sono shishi no seishin kotsuzui taru nari Not talking about the new-or-old of a time [regardless of time, in all times], and not asking about the east-or-west of a nation [irrespectrive of nation, in all nations], generally the original-colors [true qualities] of recorded-matters [accounts, chronicles] surely have been the spirit-deity bone-morrow [essence] of the lyrical-histories [historical songs, epic poems]. |

Just as there had been developments and changes of style from Homer to Virgil, there were transitions in later genres -- such as, in Kikuchi's words as cited by Tsubouchi (SZ-1 6b, Bunko 34):

|

・・・中古の小説 (羅らうマンス)より近時の人情話 (那のベル)に・・・ . . . chūko no shōsetsu (raumansu) [rōmansu] yori kinji no ninjō-banashi (noberu) ni . . . . . . from the minor-stories of middle-antiquity [medieval times] (romances) to the human-feeling-tellings of recent-times (novels) |

At this point, Tsubouchi is merely citing something Kikuchi has published as a translation. What Blair wrote and meant is not particularly important here (but see below). More significant is how Kikuchi has characterized "minor stories" about the past as "romances" (羅らうマンス raumansu > rōmansu) and "human-feeling-tellings" set in contemporary times as "novels" (那のベル noberu).

Kikuchi's style of introducing English terms in parentheses following the Sino-Japanese phrases that define them is a familiar device is peculiar in that he uses kanji to phonetically transliterate the initial syllable of the exotic word but katakana to represent the rest of the word.

Chapter 2 -- "Changes-and-movements of small-talk" (小説の變遷) -- begins with the declaration that "minor-stories" (小説せうせつ) (seusetsu > shōsetsu) are a kind of "made-up tale" (假作物語つくりものがたり) (tsukuri monogatari), an anomally (變体へんたい) (hentai) of so-called "tales of the unusual" (奇異譚 きいたん) (kiitan). He then says that "tales of the unusual" are called "romances" (羅らうマンス) (raumansu > rōmansu) in England (英國ゑいこく) (Weikoku > Eikoku), and then elaborates on "romances" as a genre.

Tsubouchi then declares that "minor-stories, that is, novels" (小説せうせつすなはち那のベル) (seusetsu sunahachi noberu > shōsetsu, sunawachi noberu) differ from romances, and elaborates on these differences. Later in the same chapter he writes "a novel, that is, a minor-story of true-formation" (ノベル即ち真成の小説) (noberu sunawachi shinsei no shōsetsu) -- which turns out to mean that a "true [accomplished] novel" is a fictional story with a plot, the unfolding of which is faithful and realistic with regard to its depictions of human emotion and behavior.

Didactic versus real

Forthcoming.

|

Didactic versus real

Booklet 3 of Tsubouchi's "Shosetsu shinzui"

At the start of Chapter 4, Tsubouchi equates "kanchō shōsetsu" with "djidakuchikku noberu" (didactic novel).

The idea that a novel is a "true" vignette of life is developed in Chapter 4, "Varieties-and-types of small-talk" (小説の種類), in which Tsubouchi differentiates two kinds of stories, those which (1) "kanchō" (勧懲) or "encourage and chastise", and those which (2) "mosha" (摸写) meaning "imitate and copy [real thing].

Tsubouchi goes on to observe that a "kanchō shōsetsu" (勧懲小説) is called a "didactic novel" (ヂダクチック・ノベル djidakuchikku noberu) in English -- and gives the rest of the first paragraph to a description of the characteristics and types of this genre. He names a number of Japanese authors and titles of maily so-called "gesaku" (戯作) or "frivolous [capricious, zany] works" -- the term most commonly used to label the often comic or jocular fictional stories that were popular from about the middle of the Edo period and well into the Meiji era.

The term "kanchō" (勧懲) is more fully expressed as "kanzen chōaku" (勧善懲悪), meaning "encourage [reward] good and chastise [punish] evil" -- which defines didacticism. Tsubouchi is swimming against the strong current of didacticism that characterizes most fictional and even non-fictional writing at the time -- even the stories on news nishikie.

Woodblock publishers justified their publications, including news nishikie, as serving the cause of moral instruction. The promotional flyer announcing the forthcoming TNS nishikie series explictly stated that one of its objects was "to teach the path of encourgement and chastisment [moral judgment] to children and women" (童蒙どうもう婦女ふじよに勧懲かんちようの道ミちを教おしゆる dōmō fujo ni kanchō no michi o oshiyuru). Two Osaka news nishikie series even included "kanzen chōaku" (勧善懲悪) in their titles.

The "novel" as "art"

For Tsubouchi, only stories that attempted to portray people as they really felt and acted as human beings, in actual social situations, qualified as "true" fiction. Those that did not attempt to be realistic, but reduced reality to questions of acts viewed as good or bad, that people ought or ought not do, were contrivances that lacked artistic qualities.

Tsubouchi -- thoroughly exposed to conventional genres of Japanese story telling -- written, performed, and sung -- was a student and translator of English romance, poetry, and drama. Having acquired a taste for the more recent modes of English fiction, he found plenty to fault in Japanese story telling, especially of the popular gesaku genre.

In his serialized essay, Tsubouchi went to great lengths to argue why gesaku and other such stories failed as true reflections of the human condition and thus could not be regarded as "art". The essay, in fact, begins with this declaration.

|

小説の美術たる由を明らめまくせば、まづ美術の何たるをば知らざる可らず。 When illuminating the reasons small-talk [the novel] is beautiful-technique [art], first we must know what is beautiful-technique [art]. |

術 (technique, method, means, way [of doing something]; strategy, scheme, design; trick, magic) is qualified by 美 (beautiful, aesthetic, attractive, pleasing, fine). As such the term 美術 has long been translationese for "art" or "fine art" -- i.e., an "art" or "craft" distinguished by the excellence of its execution.

The better-known gesaku writers of the day included Takabatake Ransen (1838-1885) -- who had signed most of the non-fiction stories he wrote for the TNS nishikie as Tentendō. Takabatake died the year Tsubouchi's essay began to be published.

Tsubouchi Shōyō (坪内逍遥 1859-1935) had graduated from Tokyo Univeristy in 1883 and became a teacher, translator, and writer rather than government employee. In 1880, while still a student, published a somewhat excised and embellished translation of Sir Walter Scott The Bride of Lammermoor. The translation was titled "Shunpū jōwa" (春風情話), meaning "Spring-wind affection-story" or "Spring romance" and, according to Ryan, "written in the metered poetic Japanese narrative style popular in the early nineteenth century" -- and otherwise presented in a manner suggesting similarities with Japanese love stories, with illustrations depicting characters in Japanese garmets (Ryan 1967:41-43).

From 1882, Tsubouchi began writing political allegories, which appeared in the illustrated newspaper Eiri shinbun and other periodicals. By 1884 he had published translations of Scott's narrative poem The Lady of the Lake and Shakespeare's Julius Caesar. By the middle of 1885, when he began writing Shōsetsu shinzui, he had added a translation of part of Edward Bulwer-Lytton's Rienzi, Last of the Roman Tribunes -- titled "Gaiseishi den" (慨世士傳) or "The life of a man who deplores [the state of] the world" -- which Ryan simplifies to "Biographie of a patriot" (Ryan 1967:44-49). All these English writers and other appear in his essay on the essence of the novel.

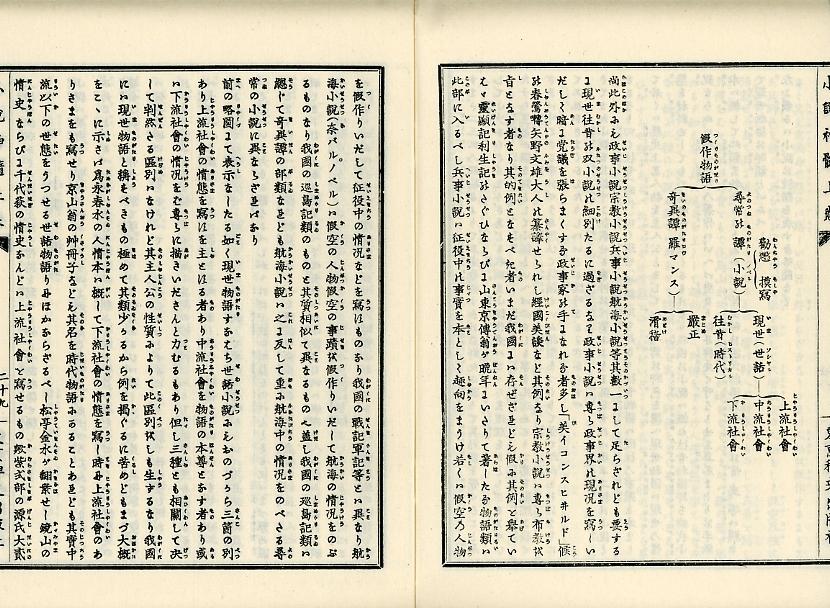

Tsubouchi's fiction taxonomy

Tsubouchi taxonomy (genesis) verus typology (attributes)

|

假作物語つくりものがたり 1. 尋常よのつねの譚ものがたり (小説ノベル) 勸懲くわんちやう 1.1 現世いま (世話ソシャル) 1.11 上流社會じやうりうしゃくわい 1.2 往昔むかし (時代ヒストリカル) 2.0 奇異譚 きいのものがたり (羅ロウマンス)

|

Meiji writing

Forthcoming.

Bakinchō

Ryan observes that "Tsubouchi wrote Gaiseishi den in the same style he had employed in Shumpū jōwa" and reiterates that "this literary style most closely resemles in its poetic qualities Western narrative poetry" (Ryan 1967:49-50). Ryan then more explictly describes this style like this (Ibid., 50, [bracketed] remarks in original).

|

When used in fiction, it was known as Bakin-chō after its most famous exponent, the early nineteenth-century novelist Takizawa Bakin (1767-1848). [Note 25] The most striking characteristic of the style is the repetition of phrases of seven and five syllables arranged in various combinations; it is therefore also frequently referred as shichigo-chō [seven-five rhythm]. The style remained very popular throughout the nineteenth century and was still widely used in the late 1880s. It soon was to become a major source of controversy among writers and critics who associated it with many of the weaknesses they considered inherent in contemporary Japanese fiction. [Note 25] Bakin's life and works are described by Leon M. Zolbrod in Takizawa Bakin: Major Edo Author. [Bibliography: Ph.D. disseration, Columbia University, 1963.] |

Takizawa Bakin (滝沢馬琴), born Takizawa Okuni (滝沢興邦), was better known as Kyokutei Bakin (曲亭馬琴), the name he used as a popular gesaku writer.

Tsubouchi's first and best known novel was Tōsei shosei katagi (当世書生気質), or "Character of today's students", published in 17 booklets from June 1885 to January 1886 (Ryan 1967:53-55), published in . . . .

RESUMEGazoku setchu

The term "gazoku setchū" (雅俗折衷) is used to describe the electic "elegant-vulgar bent-to-middle [compromise]" style developed by some writers of fiction in the late Tokugawa and early Meiji periods.

Practioners of this style sought to mix the "higher" literary expression of classical Heian literature with the "lower" vernacular expression of the times in which they lived. Their achieved this amalgamation by narrating their stories in a semblance of more classical if sometimes lighter prose, while writing dialog as it was spoken, in raw colloquial, hence sometimes very coarse, speech.

Tsubouchi devotes an entire chapter to "style" (文體, 文体 buntai), in which he differentiates "three styles" (三體, 三体 santai) -- "refined" or "elegant" (雅が ga), "course" or "vulgar" (俗ぞく zoku), and "refined-course bent-to-middle" or "compromise of elegant and vulgar" (雅俗折衷がぞくせつちう gazoku setchiu > setchū). (SZ-5 3b, Bunko 102)

He further divides the "compromised" or "electic" style into two categories, (甲) or (A) "readying-book" (稗史よみほん yomihon) style, and (乙) or (B) "grass-pamphlet" 艸冊子くさざうし kusazaushi > kusazōshi) style (SZ-6 11b, Bunko 115). The former were mostly historical tales with some illustrations, while the latter were not limited to historical stories and generally had more illustrations.

Tsubouchi speaks of the "salty-plum of the elegant-vulgar compromise" -- in which "salty plum" (塩梅あんばい anbai) is a metaphor for the "seasoning" or "flavor" or "condition" or "manner" or "bound" achieved by a "moderation" or "temperance" of salt and plum vinegar (SZ-6 12a, Bunko 116).

Genbun itchi

At the start of the Meiji period, kanbun had long been considered the medium of serious prose, whereas Japanese was used mainly for stories meant to entertain. Writing in the language (if not exactly the manner) that people actually spoke was seen as facilitating the objects of compulsory education and other nation-building projects. Writing in Japanese also gained in prestige as a medium for serious discourse and fiction.

The public use of kanbun had all but disappeared by the end of 19th century. Education in kanbun classics remained strong in public schools until the end of World War II, after which it began to lose its status. By the end of the 20th century, kanbun literacy had all but vanished.

The abandonment of kanbun came about as a result of the a movement called "genbun itchi" (言文一致) or "speech-writing unification [agreement, accord, congruence, consistency]" (my translation) movement that began during the Meiji period. The object the movement was to bring the styles of writing closer to those of speech.

The movement contributed not only to the demise of "kanbun" (漢文) or "Chinese writing" in favor of writing in Japanese, but also to the vernacularization of Japanese writing. The writer to most clearly demonstrate the possibilities of a newer, more realistic writing style was novelist and translator Futabatei Shimei (二葉亭四迷 1864-1909), who was strongly encouraged and influenced in his efforts by his friend Tsubouchi.

Massimiliano Tomasi observes, as do many others, that "The four major varieties were kanbun 漢文 (Sino-Japanese), wabun 和文 (classical Japanese), sōrōbun 候文 (epistolary style) and wakan konkōbun 和漢混交文 (a style characterized by a combination of Chinese and Japanese elements)" (Tomasi 1999, page 333, note 1; essentially the same observation is made in Tomasi 2004, Chapter 7, note 1, pages 105 and 185).

Kikuchi Dairoku

The most important study of rhetoric in the Meiji period was Bijigaku (美辭學、美辞学 Bijigaku) by Takada Sanae (高田早苗 1860-1938) writing as Takada Hanpō (高田半峰). Published in two volumes in Meiji 22 (1889), it followed several studies by other writers, beginning with Kikuchi's work a decade earlier.

It was Kikuchi's work, however, that inspired Tsubouchi's efforts to classify genres of fiction and define what was essential to quality contemporary fiction.

Takada, like Kikuchi, was a politician and educator. Both men went on to serve terms as the Minister of Education, Kukuchi in 1901-1903 and Takada in 1915-1916, and were heads of universities, Kikuchi of Kyoto Imperial University, Takada of Waseda University.

Kikuchi, the first Japanese to graduate from Cambridge, having studied phyics and mathematics, is best remembered in Japan as a mathematician and author of a geometry textbook. His grandson, by his eldest daughter, was the socialist politician Minobe Ryōkichi (美濃部亮吉 1904-1984), Tokyo's governor for 22 years (1967-1979) and a national House of Councilors parliamentarian the last four years of his life.

Takada married the eldest daughter of Maejima Hisoka, who was instrumental in nationalizing Japan's postal system and launching Yūbin hōchi shinbun.

Hugh Blair

Numerous editions of Blair's work, some with commentary, were available at the time Kikuchi wrote his study. The original collection runs several hundred pages, whereas Kikcuhi's study, published in two small folio volumes, dealt mostly with what Blair had to say about "fictitious history" -- referring to "romances" and "novels".

In the last 13 of his 47 lectures, Blair named and defined four categories of writing -- historical writing, philosophical writing, fictitious history, and poetry. The first three of these final chapters are titled as follows.

Chapter XXXV. Comparative Merit of the Ancients and Moderns -- Historcial Writing

Chapter XXXVI. Historial Writing

Chapter XXXVII. Philosophical Writing -- Dialogue -- Epistolary Writing -- Ficticious History

The 10 chapters following these concern various categories of poetry, the last two of which were Tragedy and Comedy as forms of Dramatic Poetry.

The following text is a cut-and-paste of extracts of Blair's lectures, posted as part of a hypertext presentation called Hugh Blair 1718-1800, prepared by Michigan State University graduate students Gloria Nixon-John and Annie Ransford for a course on rhetoric. Ellipses and brackets as received.

|

Lecture XXXVII. Philosophical Writing -- Dialogue -- Epistolary Writing -- Fictitious History Of philosophy the professed design is instruction. With the philosopher, therefore, style, form, and dress are inferior objects. But they must not be wholly neglected. The same truths and reasonings, delivered with elegance, will strike more than in a dull and dry manner. Beyond mere perspicuity, the strictest precision and accuracy are required in a philosophical writer; and these qualities may be possessed without dryness. Philosophical writing admits a polished, neat, and elegant style. It admits the calm figures of speech; but rejects, whatever is florid and tumid. . . . Among the ancients, philosophical writing often assumed the form of dialogue. Plato is eminent for the beauty of his dialogues. In richness of imagination, no philosophic writer, ancient or modern is equal to him. In epistolary writing we expect ease and familiarity; and much of its charm depends on the writer. Its fundamental requistes, are nature and simplicity, sprightliness and wit. The style of letters, like that of conversation, should flow easily. It ought to be neat and correct, but no more. [Fictitious history] . . . includes a very numberous, and in general a very insignificant class of writings, called romances and novels. Of these, however, the influence is known to be great, both on the morals and taste of a nation. Notwithstanding the bad ends to which this mode of writing is applied, it might be employed for very useful purposes. Romances and novels describe human life and manners, and discover the errors into which we are betrayed by the passions. Wise men in all ages have used fables and fictions as vehicles of knowledge; and it is an observation of Lord Bacon, that the common affairs of the world are insufficient to fill the mind of man. He must create a world of his own, and wander in the regions of imagination. All nations whatwoever have discovered a love of fiction, and talents for invention. . . . Interesting situations in real life are the groundwork of novel writing. Novels furnish one of the best channels for conveying instruction, for painting human life and manners, for showing the errors into which we are betrayed by our passions, for rendering virtue amiable and vice odious. The effect of well contrived stories, towards accomplishing these purposes, is stronger than any effect that can be produced by simple and naked instruction. . . . The trivial performances which daily appear under the title of lives, adventures, and histories, by anonymous authors, are most insipid, and, it must be confessed often tend to deprave the morals, and to encourage dissipation and idleness. |

Tomasi on Kikuchi and Tsubouchi

Massimiliano Tomasi makes the following statement about Kikuchi Dairoku's Shūji oyobi kabun (Tomasi 2004, page 65, Notes and Bibliography, underscoring mine, [square brackets] mine, <angular brackets> based on Tomasi).

|

By the end of the second decade of the Meiji period, several books on rhetoric had already been published, but these mostly dealt with oratory and did not consider the study of rhetoric as a field concerned with writing and literary criticism. However, one work, Kikuchi Dairoku's Shūji oyobi kabun [< Rhetoric and belles lettres, 1879 >], had already sought to address rhetoric in those very terms. Kikuchi (1855-1917), a mathematician, had been commissioned by the Ministry of Education to translate "Rhetoric and Belles Lettes," a piece that had appeared in William and Robert Chambers' encyclopedia, Information for the People (1867). This work was in turn largely based on Bain's English Composition and Rhetoric. [Note 1]

|

Tomasi further remarks about the importance of Kikuchi's work generally, and as a source of inspiration for Tsubouchi Shōyō particularly (page 67, underscoring mine, [square brackets] mine, <angular brackets> based on Tomasi)

|

. . . Thus except for Shōyō's Shōsetsu shinzui (The essence of the novel, 1885-1886), which was, strictly speaking, not a treatise of rhetoric, more than ten years would pass before rhetoric was once again addressed as a field of study concerned with literature and literary criticism. It is not a coincidence that Shūji oyobi kabun has been considered by many as an essential step toward the modernization of Japanese literature. Already at the beginning of the twentieth century, . . . . Shūji oyobi kabun has thus enjoyed substantial recognition among scholars, some of whom have gone so far as to regard it as the beginning of Japanese literary criticism. This is especially so in light of the influence it is said to have exerted on Tsubouchi Shōyō's theory of the modern novel. It is well known that Shōyō (1859-1935) acknowledged Kikuchi's translation in a piece published in 1925. [Note 7] While it is possible to speculate that this acknowledgment may have been the very reason for Shūji oyobi kabun's later fortune, some scholars have discussed at length the clear influence of Shūji oyobi kabun over Shōsetsu shinzui.

|

Something is odd here -- because it is clear that Tsubouchi had directly acknowledged Kikuchi Dairoku by name, and Shūji oyobi kabun by title, in 1885, in Shōsetsu shinzui, when substantially quoting the pamphlet edition of Kikuchi's translation (see above). The influence of the terminology and even the classification scheme in Kikuchi's translation on Tsubouchi is also transparent.

Hui Wu on Kikuchi

Studies of "rhetoric" by Japanese during the Meiji period, based on European, particularly English theory and practice, inspired similar studies in China, according to Hui Wu, a professor of English in the Department of Literature and Languages at The University of Texas at Tyler, and the editor of Once Iron Girls: Essays on Gender by Post-Mao Chinese Literary Women (Rowman and Littlefield, 2009).

Wu is also the author a 2009 essay on of the following essay Rhetoric Review, which earned her the 2009 Theresa J. Enos 25th Anniversary Award for year's best article in the journal.

Hui Wu

Lost and Found in Transnation: Modern Conceptualization of Chinese Rhetoric

Rhetoric Review

Volume 28, Issue 2 (April 2009)

Pages 148-166

An Internet abstract of this article reads like this.

|

Why do the Chinese relate rhetoric only to stylistic devices in writing? This question, which has puzzled scholars for decades, is finally answered. Modern Chinese rhetoric began to form in the late 1800s when Chinese students learned Western rhetoric from their Japanese professors, who translated it into "the study of beautiful prose," subsequently severing it from oratory. In the early twentieth century, scholars returning from Japan and the US integrated Japanese theories and Anglo-American figures of speech into Chinese literary and literacy traditions despite nativists' protests and appropriated them into a canon of aesthetics only for writing studies. |

Wu comments on the title of Kikuchi's work as follows (pieced together from web teasers).

|

Their [Chinese students in Japan] professors included Takada Sanae, Shimamura Hogetsu, and Igarashi Chikara. Takada was the author of Bijigaku, the first Japanese work that translated rhetoric into "study of beautiful prose" [Note 2] . . . |

Sources

Forthcoming.

Writing and rhetoric

Tomasi 2004

Massimiliano Tomasi

Rhetoric in Modern Japan

(Western Influences on the Development of Narrative and Oratorical Style)

Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2004

x, 214 pages, hardcover

Tomasi's book is nicely reviewed by Dennis C. Washburn in The Journal of Japanese Studies, Volume 32, Number 1 (Winter 2006), pages 195-199.

In an earlier monograph, Tomasi wrote on the so-called "genbun itchi" (言文一致) -- which he dubs or "unification of the spoken and written language".

Massimiliano Tomasi

Quest for a New Written Language: Western Rhetoric and the Genbun Itchi Movement

Monumenta Nipponica (Sophia University)

Volume 54, Number 3 (Autumn 1999)

Pages 333-360

Substantial parts of this article inform "Rhetoric and the Genbun Itchi Movement", Chapter 7 in Tomasi 2004 (pages 105-128).

Wu 2009

The following essay by Hui Wu, on the development of "rhetoric" in China, via England and Japan, earned her the 2009 Theresa J. Enos 25th Anniversary Award for year's best article in Rhetoric Review, a journal on rhetoric and composition published by the Department of English at The University of Arizona, where she had been teaching.

Hui Wu

Lost and Found in Transnation: Modern Conceptualization of Chinese Rhetoric

Rhetoric Review

Volume 28, Issue 2 (April 2009)

Pages 148-166

Takabatake Ransen

Forthcoming.

Takagi Gen

The scholar most active in studies of Takabatake Ransen today is Takagi Gen, a professor at Chiba University who specializes in the popular "minor stories" of 19th-century Japan.

高畠藍泉

怪化百物語

高木元 (校注)

解説:高畠藍泉の時代

ページ353-392 (解説:431-453)

(日野・他 2004)

Takabatake Ransen

Kaika hyaku monogatari

[One-hundred tales of [civilization as] mystification]

Takagi Gen (rectification and annotation)

Kaisetsu: Takabatake Ransen no jidai

[Commentary: Takabatake Ransen's era]

Pages 353-392 (Commentary: 431-453)

(In Hino et al. 2004)日野龍夫、中野三敏、小林勇、高木元 (校注)

Hino Tatsuo, Nakano Mitsutoshi, Kobayashi Isamu, Takagi Gen (rectification and annotation)

開化風俗誌集

Kaika fūzokushi shū

[Civilization (Enlightenment) manners-and-customs journals anthology]

新日本古典文学大系:明治編1

Shin Nihon koten bungaku taikei (SNKBT)

[New Survey of classical literature of Japan]

Meiji-hen 1

[Meiji compilation No. 1]

東京:岩波書店、2004

Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2004

8 (目次、凡列), 443 (本文) ページ、函

8 (contents, notation), 443 (text) pages, boxed

For more about Takabatake Ransen as a writer, see particularly TNS-876 Mysterious incidents and TNS-876 Mysterious incidents on this website.

For web versions of Takagi's transcription of Kaika hyaku monogatari and his article on Takabatake's life, and other features related to "minor stories" in 19th-century Japan, see Takagi's website, Fumikura (Text Archives).

Tsubouchi Shoyo

Numerous monographs and books have been written entirely or significantly about Tsubouchi Shōy"ō. Three have been most useful for my purposes.

Shosetsu shinzui pamphlet facsimiles

The original nine booklets (冊), representing two volumes (巻 kan), were published between 1885 and 1886. The nine booklets were apparently first sold as two bound volumes as early as 1876.

The following facsimile edition seems to have been first printed as early as 1968 and as late as 1985.

坪内逍遥

小説神髄

精選 名著復刻全集

東京:近代文学館、昭和51年2月1日 (第7刷)

総発売元:ほるぷ

全九冊 (上巻、下巻)、函Tsubouchi Shōyō

Shōsetsu shinzui

[Divine marrow of minor stories]

Seisen:Meicho fukkoku zenshū

[Complete collection of reprints of select famous works]

Tokyo: Kindai Bungaku Kan, 1976 (7th printing)

[Repository of recent-era literature]

< Museum of Modern Japanese Literature >

Production and sales: Horupu

9 booklets representing two volumes in one box

The publishing particulars of the above facsimile edition are as follows.

東京府平民:坪内雄蔵

Tōkyō-fu heimin: Tsubouchi Yūzō

[Tokyo-prefecture commoner Tsubouchi Yūzō]

東京本郷區湯島切通町三番地:松月堂

Tōkyō Hongō-ku Yushima Kiridōshichō 3-banchiThe cover bills Tsubouchi Yūzō as a "man of letters" (文學士 bungakushi). Tsubouchi's address was also in Hongō-ku. The publisher's name was Matsunaga Sakujirō (松永作次郎).

Publication dates

All nine booklets were published under the same "publication license" (版権免許 shuppan menkyo) of Meiji 18-4-9 (9 April 1885).

Actual publication (出版), however, did not begin until September and was not completed until the following April. All volumes show the colophon on the inside of the front cover, except Booklet 3, which shows it in the back (and exceptionally shows a day as well as month).

Vols 1-2, M18-9 [September 1885]

Vol 3, M18-9-26 [26 September 1885]

Vol 4 M19-3 [March 1886]

Vols 5-9 M19-4 [April 1886]Pagination

The 9 fascicles (冊 satsu), or string-bound pamphlets, are paginated as two volumes (巻 kan). Each contains around 10 folios (丁 chō), or folded leaves, each numbered in the middle where the leaf is folded so as to have a first (front) and second (back) page. Front matter and main text are paginated separated.

Vol 1: 2 (序), 1 (上巻目次), 1-10 (本文)

Vol 2: 11-20

Vol 3: 21-30

Vol 4: 31-40

Vol 5: 1 (下巻目次), 1-9 (本文)

Vol 6: 10-19

Vol 7: 20-29

Vol 8: 30-39

Vol 9: 40-48

National Institute of Japanese Literature edition

The National Institute of Japanese Literature has published, in one volume, what appears to be a copy of the two-volume bound edition in the possession of Yamanashi University Library. I have not seen a physical copy of this publication. However, judging from images of several pages shown on Amazon.co.jp, the typography is the same as that of the above pamphlet facsimile edition -- as one would expect to see in an edition produced by consolidating the pages of a run of thinner pamphlets into a thicker booklet.

坪内逍遥 (つぼうちしょうよう) < Tsubouchi Shōyō

小説神髄 (しょうせつしんずい) < Shōsetsu shinzui >

東京:国文学研究資料館、2007-3-25

Tokyo: National Institute of Japanese Literature, 2007

リプリント日本近代文学 88 [Reprint Japan recent-era literature 88]

所蔵:山梨大学附属図書館 [Ownership: Yamanashi University Library]

販売:平凡社 [Sales: Heibonsha]

印刷:オンデマンドジャパン [Printing: On Demand Japan] 総ページ202 [202 general pages]

Iwanami bunko editions

Among popular editions of Shōsetsu shinzui, the longest seller has been Iwanami Shoten's paperback edition, first published in the 1930s. The edition in print today continues

小説神髄

東京:岩波書店、1988-2-4 (第17刷)

268ページ、岩波文庫

第1刷 (1936-10-15)

解説:柳田泉、ページ 5-14 (昭和十一年夏八月)

岩波文庫創刊60年記念リクエスト復刊 (第2回)

Tsubouchi Shōyō

Shōsetsu shinzui

[Divine marrow of minor stories]

Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1988-2-4 (17th printing)

268 pages, Iwanami Bunko (paperback)

1st printing (1936-10-15)

Commentary: Yanagida Izumi (1894-1969), pages 5-14

Commentary dated 1936, Summer, August

Republished with other volumes in commemoration of

60th anniversary of Iwanami Bunko (1927-1987)

Marleigh Ryan

The most important works about Tsubouchi in English are the following two volumes by Marleigh Ryan.

Marleigh Grayer Ryan

Japan's First Modern Novel: Ukigumo of Futabatei Shimei

(Translation and Critical Commentary)

New York: Columbia University Press, 1971 (second printing)

[Copyright 1965, first printed in book form 1967]

xvi, 381 pages, softcoverMarleigh Grayer Ryan

The Development of Realism in the Fiction of Tsubouchi Shōyō

Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1975

133 pages, hardcover