TNS news nishikie

Taiwan Expedition prints

By William Wetherall

First posted 1 September 2005

Last updated 20 January 2007

Implications of cherubs and seals for Taiwan Expedition prints

Taiwan Expedition prints

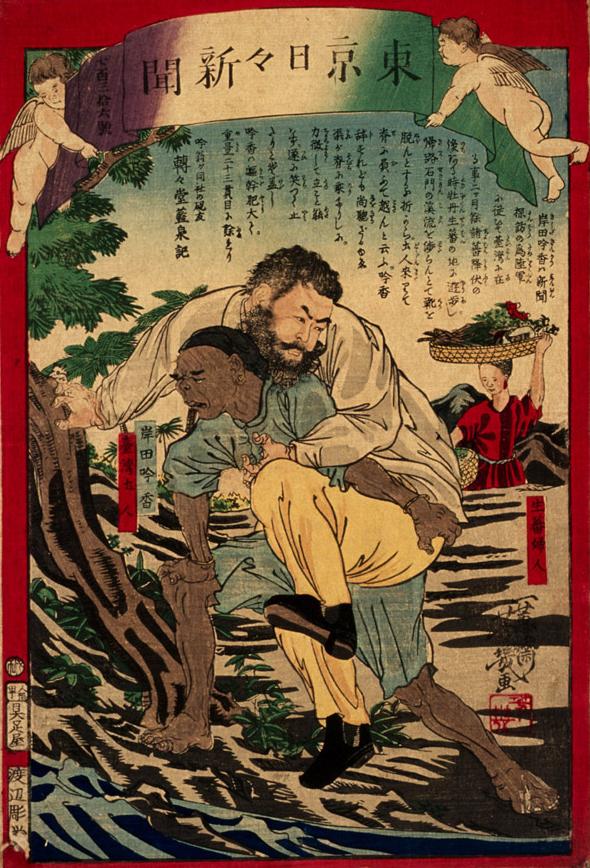

Kishida Ginko (TNS-736)

|

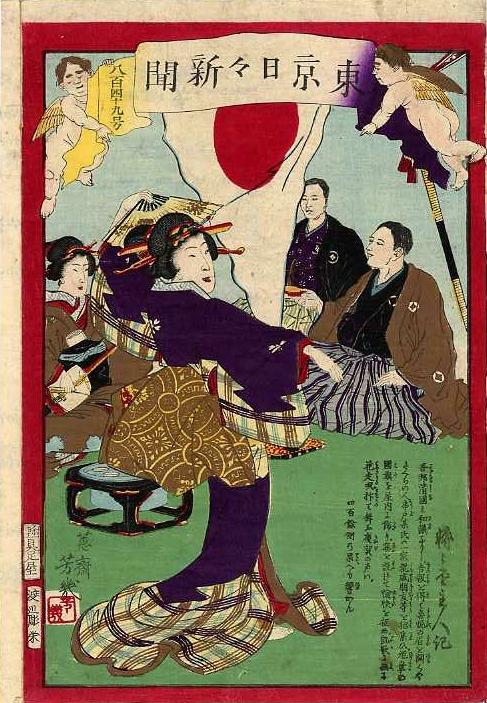

Botan girl (TNS-726)

|

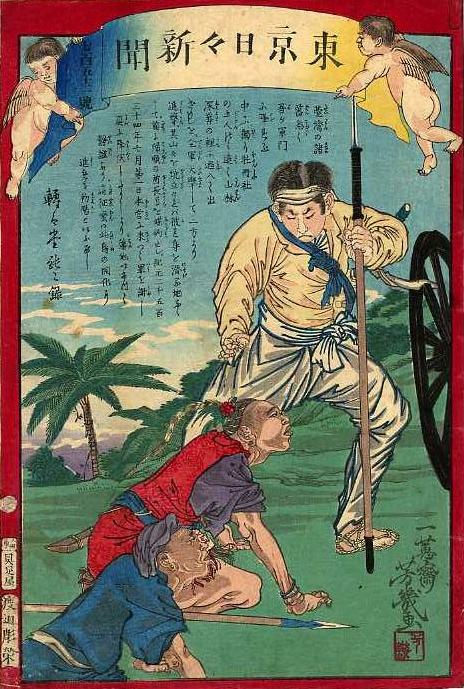

Natives sumbit (TNS-752)

|

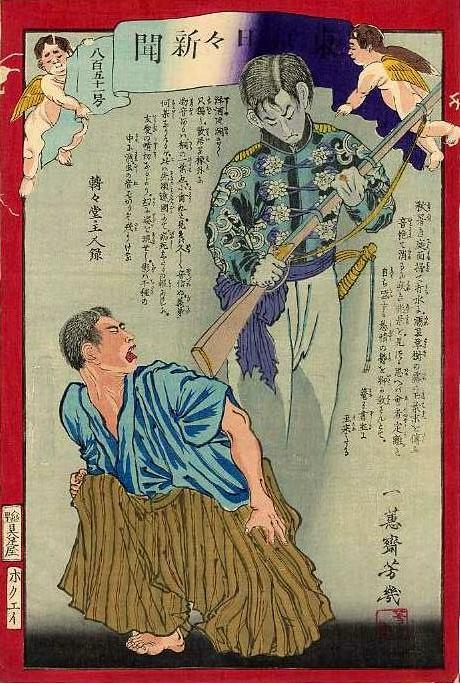

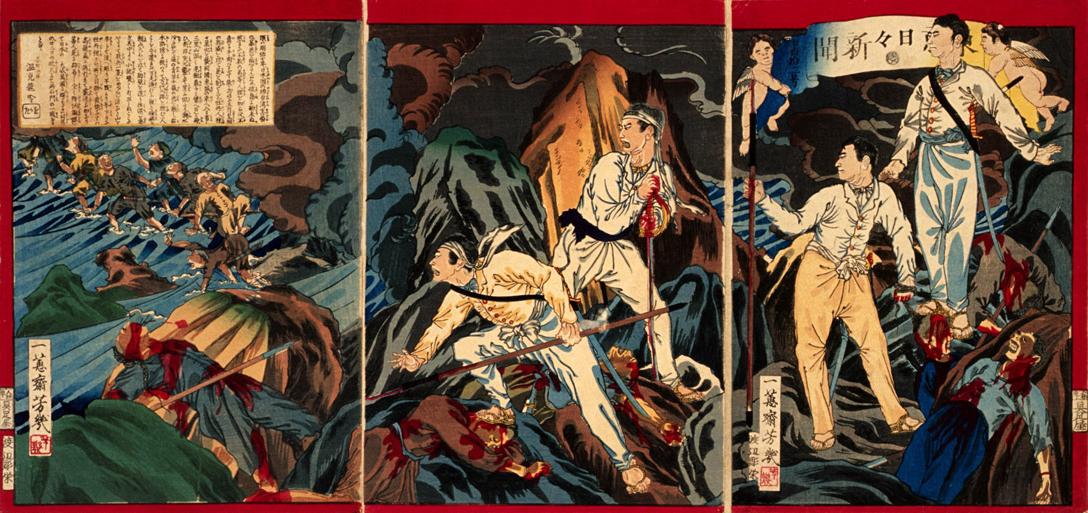

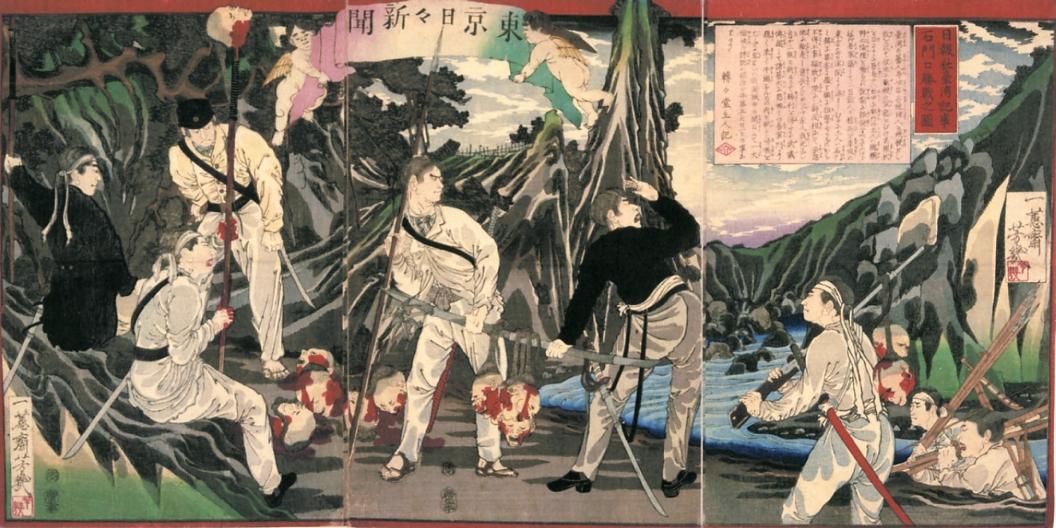

Battle at Stonegate (TNS-712, TNS-9002)

|

Celebration and grief (TNS-847, TNS-849, TNS-851)

Strike while it's hot

Implications of cherubs and seals for Taiwan Expedition prints

If this hypothesis is correct, then the Taiwan Expedition prints were published in the following order.

1. TNS-736 (Cherub 1, 1874-09)

This print, published in September, shows Japan's first overseas war correspondent Kishida Ginko in the war zone, being ported across a river by a Taiwanese man. Kishida accompanied Saigo Tsugumichi's expedition to Taiwan, in order to gather news for Tokyo nichinichi shinbun. The Tonichi nishikie series on the expedition was not published until his return. And the series began with a print that featured the reporter who fed the broadsheet with eye-witness accounts of the war.2. TNS-726 (Cherub 1, 1874-10, 卍)

This print, published in October, shows a Botan girl wearing kimono, to symbolize native acceptance of Japanese culture.3. TNS-752 (Cherub 1, 1874-10, X)

This print, also published in October, shows two native men kowtowing in a gesture of offering their allegiance to Japan.4. TNS-712 and TNS-9002 (Cherub 2, 1874-10, X)

Both of these prints, published in October, are triptychs depicting two phases of the Battle of Stonegate. They may have been published together. Or TNS-712 might have been published first, as it shows the battle in progress. Then the unnumbered print, shows the results of the battle, would have been published. The unnumbered print, rarely seen, shows Japanese soldiers carrying heads they had severed and taken as trophies. Some heads are hanging from poles in rope slings like water melons. One is skewered on the point of a lance carried like a regimental flag.5. TNS-847, TNS-849, and TNS-851 (Cherub 2)

This group of prints had to have been published in late November or even December, as they are based on stories that were not reported in the broadsheet until early or mid November.

This order makes sense in terms of how the Taiwan Expedition eventually "came to Japan" as it were. Of course it was reported in bits and pieces in the broadsheets. But it took some time for eye-witnesses to return to Japan to give more detailed and personal accounts.

Background of Taiwan Expedition prints

Forthcoming.

1. Native carries Kishida

TNS-736, showing Native carries Kishida, was based on a story in the M7-07-07 (7 July 1874) issue of Tokyo nichinichi shinbun, the broadsheet. The Tonichi story was an article from the No. 22 issue of Taiwan shinpo (台湾信報) [Taiwan news], a bulletin Kishida Ginko posted from Taiwan. He was still in Taiwan at the time, and the dateline of the article read "17 June, Checheng Headquarters" -- referring to Saigo Tsumumichi's expeditionary headquarters on the coast of the Hengchun peninsula at the southern tip of Taiwan. (Ono 1972:152)

Yoshiiku was known for his ability to capture character in portraits. His caricature of Kishida in TNS-736 is in fact a very easily recognizable likeness of this much photographed and worldly man -- who helped Hepburn edit the first Japanese-English dictionary in Shanghai in the late 1860s, promoted business with China, and became a Tonichi reporter in 1873.

2. Taiwan botan girl

TNS-726 tells the story of the Taiwan Botan Girl, as reported in the 26 June issue of Tonichi. The Tonichi story was based on an article by Kishida in the No. 17 issue of Taiwan shinpo, in which he reports having seen the girl on or about 4 June in Checheng, said she was 12 or 23 years old, and like a monkey. Another story about the girl, in the 29 June edition of Tonichi (TNS-729), ran a portrait of her and described her character. Sponsors had arranged for her to come to Japan and on the ship she learned to use chopsticks.

In Tokyo she was placed in the care of a family and given the name "Otai" since apparently she didn't know the her mother's or father's names or even her own. By September she was able to respond to people, presumably in Japanese.

The 17 November issue of Tonichi reported that on the 13th she had left on a ship for Nagasaki enroute back to Taiwan, having been the merciful care of one Japanese benefactor or another for five months. The 30 December issue (TNS-893) reported she had arrived back in Taiwan on 24 November. (Ono 1972:152)

Yoshiiku made an attempt to portray the girl as she probably looked. As one of the founders of Tonichi and an illustrator, he may have drawn the likeness of the girl that appeared in the paper. In any event he would have seen the portrait in the paper, and he also might have seen the girl when she was in Tokyo, or gotten an account of her appearance from Kishida, who by then was probably back in Japan.

3. Taiwan natives submit

TNS-752 shows how Taiwan Natives Submit to a Japanese soldier after their defeat, at least in Yoshiiku's imagination, as reported in the 25 July 1874 issue of Tonichi. The article originally appeared in the No. 25 issue of Taiwan shinpo. The gist of Kishida's report was that Saigo's punitive expedition had largely achieved its mission.

Despite the overall accuracy of Kishida's reports, and the relatively small scale of the fighting and low casualty rates on both sides (about 7 Japanese and 30 Taiwanese were killed in the Battle at Stonegate), in Tokyo there were rumors Saigo's forces were engaged in a major war with the Chinese army, that over half of his soldiers had died from poison arrows, or had been done in by poisonous snakes, and that Saigo himself had been killed by savages. However, the expedition, which included about 2000 soldiers, was not prepared to fight disease, though, and by the time it returned to Japan, about 500 hundred had succumbed to Malaria. (Ono 1972:153; death figures from other sources)

Here is a translation of the text accompanying Yoshiiku's depiction of kowtowing natives, written by Tentendo Dondon (Takabatake Ransen), as translated by Robert Eskildsen, a professor of Japanese history at Smith College, who is writing a book on the Taiwan Expedition (Robert Eskildsen, "Of Civilization and Savages: The Mimetic Imperialism of Japan's 1874 Expedition to Taiwan", in The American Historical Review, Volume 107, Issue 2, April 2002, pages 388-418; page 37 of web edition; brackets and contents are Eskildsen's).

All the savages of Taiwan have surrendered to our forces, but among them the savages of only the Botan [Butan] tribe fled deep into the mountains and did not come out, [so] the entire army attacked in mass from three directions, setting fire to the mountains so that they had no place to hide. The chiefs who had already submitted [kijin] acted as intermediaries, and on the first day of the seventh month of the year 2534 of imperial rule [kigen] [1874], [the Butan] came to the headquarters to apologize for [their] transgressions, and they surrendered in earnest. Thereafter the savage land became completely tranquil. It must be said that this expedition to punish the savages is the first stage in advancing the enlightenment [kaika] of the island.

4. Battle at Stonegate triptychs

TNS-712 and TNS-9002, both triptychs, present two very different accounts of the Battle at Stonegate, a natural pass in the Mutan mountains that rise from the coast of Hengchun, where Saigo's troops collided with Mutanshe villagers.

In TNS-712, which I have dubbed Yoshiiku's Stonegate 1, Yoshiiku depicts the battle that he imagined raged at Stonegate, as reported in the 10 June 1874 issue of Tonichi, extracted from an article in the No. 13 issue of Kishida's Taiwan shinpo. The article appears to have been Kishida's first report of fighting. Kishida had gone by sea to Nagasaki from Shinagawa in Tokyo. He disembarked for Taiwan on Saigo's flag ship, the steamer Takasago, at noon on 17 May, and arrived at Checheng at seven in the morning of 22 May. Apparently he sent his reports to Japan through military communication channels. (Ono 1972:151-152)

The story accompanying Yoshiiku's triptych was written by Onkoku Ryugin, who appears to have been the journalist Okada Jisuke. Here is a partial translation of the story by Eskildsen (ibid., page 28; brackets and ellipses are Eskildsen's).

It was in the seventh year of Meiji [1974] when Japanese soldiers came to this island to punish the violence of the Taiwan raw savages. But the untutored barbarians do not know ethics and they attacked without warning, so at last the hideout of the Botan [Butan] race was attacked in May in order to suppress them with the military power [hei'i] of the empire [kokoku] . . . [for their defense, the Butan] relied on cliffs so steep that a single person defending could impede the advance of ten thousand, and using large stones they made battlements that blocked any movement. From within this [stronghold] they let loose a hail of gunfire. At this point our troops contrived a plan. They managed with great effort to circle around a mountain that had no footpaths, and aiming down on the stronghold of the Botan from the side of the mountain they fired, [their gunfire] like hail pelting down in an onslaught by a strong mountain storm. The savages lot heart and they surrendered and apologized, and at dawn on May 22 Japan's imperial prestige [ten'i] shone before the world [bankoku] in this battle at Sekimon.

Eskildsen observes that, despite the description of the battle as one involving rifles, Yoshiiku portrayed only swords in his triptych. After going on about "Western" this and "samurai" that, Eskildsen says this by way of comparing Yoshiiku's triptych with one done a month later by Yoshitoshi (Ibid., page 31).

The European aspect of the soldiers' appearance in Yoshiiku's print may have provided a general idea of how members of the expeditionary force actually looked, but their appearance also surely evoked an awareness of samurai resistance to Western influence in Japan. Yoshiiku's portrayal of the soldiers seems to betray an awareness of this resistance, because he chose not to portray rifles, a weapon that true samurai scorned as beneath their dignity and that some samurai saw as a Western perversion of Japan's purity. His choice seems all the more deliberate since newspaper articles -- and even the text by Okada that appears on the print -- highlighted the Japanese use of rifles, and since his greatest rival at the time, the woodblock print drawer Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, accentuated the Japanese use of rifles in his print about the battle at Sekimon.

This is a reasonable observation, though it is far from clear what Yoshiiku intended by his depiction of Japanese soldiers in white armed only with swords and spears. At least the natives are armed with the same sort of weapons.

Yoshitoshi's Stonegate, drawn with the help of his disciple Yoshimitsu, was published in November 1874, a month after Yoshiiku's two triptychs came out. It shows Japanese soldiers, in black pants and red blouses, firing into a village they have surrounded. The high resolution scan of this print on Tsuchiya's CD-ROM shows that the natives are predominately armed with spears, followed by bows and spears. The very few rifles among them are small mostly because they are in the distance. Even then, then do seem a bit flimsy compared with the rifles of the Japanese troops in the foreground. Still, it is not clear that Yoshitoshi "accentuated" the use of rifles by these troops. It seems to me he just showed them.

Nor is it true that Yoshiiku did not depict rifles. In the unnumbered TNS-9002 triptych, which I have dubbed Yoshiiku's Stonegate 2, Yoshiiku shows several soldiers carrying heads as trophies after their victory. One of the soldiers is carrying a head he has slung from the barrel of his rifle. It is easily the most graphic of all the news nishikie prints on the war -- though strictly speaking it not really part of the TNS news nishikie series (click the above link to read why).

5. Celebration and grief

The remaining Taiwan Expedition prints in the TNS series were published after October, since they are based on news reports that did not appear in Tonichi until November.

TNS-847 China Detente Triptych shows panorama of the signing at Peking, in the witness of third nation delegates, of the treaty of amity which settled the dispute between the governments of China and Japan over the acts of Tawainese natives against Ryukyuan storm refugees. |

|

TNS-849 Showing the Flag shows people in Japan celebrating the end of the dispute that had led to the Taiwan Expedition This Gusokuya edition of this print was so popular that Tsujibun, who bought some of Gusokuya's TNS blocks, also published it. |

|

TNS-851 Taiwan Expedition Ghost is about a man named Kobayashi who was reportedly depressed by the fact that his brother-in-law, a man named Saito, was killed in the war and didn't come back -- except as a ghost to haunt him. It seems that Kobayashi, if not a family member or friend, complained about the story, and the mention of his name in a cartouche by his figure on the print. For a second edition of the print was issued without the name cartouche and with a new text. |

Strike while it's hot

The stories that inspired the last three prints appeared in rapid succession. Presumably the prints also came out fairly shortly after the newspaper reports and were closely spaced -- capitalizing on celebrations of the victory, and the end of a conflict that had nagged some Japanese for three years.

September, October, and November 1874 were busy months for woodblock publishers trying to profit on public interest in the Taiwan Expedition. The war, though fought that spring, didn't come to Japan -- as it were -- until that summer, when the Botan maiden came to Tokyo. And peace talks with China didn't bear fruit until that fall.

All in all, Yoshiiku and Gusokuya milked the war for a total of seven prints. And Yoshiiku and Hirooka squeezed out another. That's eight prints in the space of three months, out of about 110 that bore the Tonichi banner in the course of about one year.

No other story was so well covered by such visual media at the time -- except the Shogitai memorial that same year -- and, three years later, the Seinan War, which ended with the death of Saito Takamori, Tsugumichi's older brother. One would like to think that Tsugumichi, after his adventures in Taiwan, decided he had had enough fighting for one lifetime and maybe more.