| Bibliography of news nishikie related publications | ||||

| Introduction | General | Stories | Drawings | Topics |

History

•

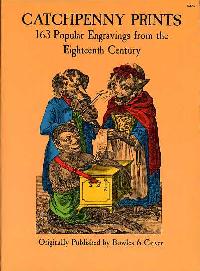

Bowles and Carver 1970

•

Chibbett 1977

•

Formanek and Linhart 2005

•

Furusho 1998

•

Henderson 1983

•

Higuchi 1962

•

Hillier 1987

•

Illing 1980

•

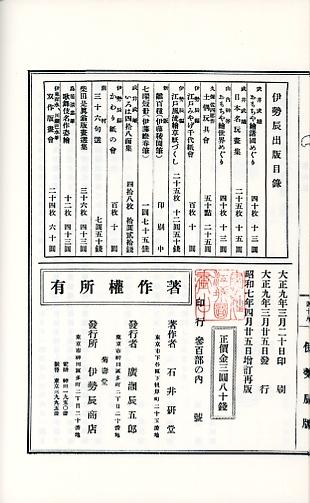

Ishii 1920

•

Ishii 1929

•

Itabashi 2004

•

Kobbe 1913

•

Koshi 1989

•

Merritt and Yamada 2000

•

Nagata 1992

•

Newland 2004

•

Ryoji 1976

•

Shepard 1962

•

Shepard 1973

•

Shimonaka 1979

•

Suzuki 1971

•

Takahashi 1991

•

Takahashi 1992b

•

Tanaka 1986

•

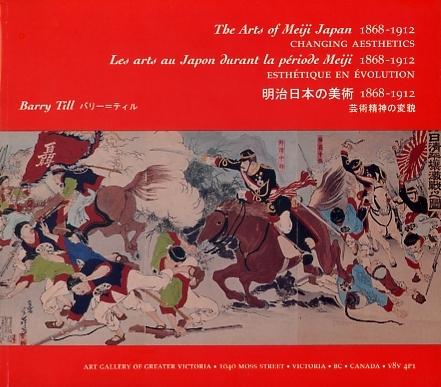

Till 1995

•

Tomizawa 2004

•

Tsuji 1999

•

Uchida 2007

•

Uemura and Takamizawa 1931

•

Unno 1995

•

Yamada 2005

Publishers

Matsuki Heikichi I-V (circa 1764 to 1923)

•

Ukiyoe 1968-34

Drawers

Kuniyoshi (1798-1861)

•

Geijutsu shincho 1992-05

Ekin (1812-1879)

•

Chikamori 1997

Kawanabe Kyosai (1831-1889)

•

Geijustu shincho 1998-06

Yoshiiku (1833-1904)

•

Higuchi 1926

•

Kinoshsita 1996

•

Okado 1995

Yoshitoshi (1839-1892)

•

Akita 1999

•

Bessatsu Rekishi dokuhon 1988-07

•

Bijutsu techo 1974-11

•

Geijutsu seikatsu 1976-05

•

Geijustsu shincho 1994-09

•

Hanawa and Maruo 1988

•

Keyes and Kuwayama 1980

•

Keyes 1982

•

Mizue 1973-11

•

Mizue 1977-08

•

Narasaki et al 1977

•

Segi 1978

•

Segi 1985

•

Soya et al 1971

•

Shimamura 1999

•

Ukiyoe 1978-75

•

van den Ing and Schaap 1992

•

Yashiro 1982

•

Yokoo 1989

•

Yoshida and Isao 1992

Kiyochika (1847-1915)

•

Gunma 1986

•

Smith 1988

•

Yamanashi 1997

Ito Seiu (1882-1961)

•

Geijustsushincho 1995-04

Kishida Ryusei (1891-1929)

•

Geijutsu shincho 2000-02

Publications about printed drawings and their producers, with a focus on news illustration in mid-19th-century Japan, are found here. General works about drawings and drawers, and about the publishing industry including drawing, carving, printing, and distribution, are grouped under History. Works about publishers, drawers, carvers, printers and others involved in the production of drawings are listed by year of founding or birth. Studies of drawings related to specific topics -- murder in art, suicide in art, Satsuma War through nishikie -- are in the "Topics" section.

| History of printed drawings and their producers |

Bowles & Carver (original publisher) This book reproduces a collection of late 18th-century broadsides, all printed by the London firm of Bowles and Carver, reprinted for the first time in almost 200 years. The back cover blurb goes on to say:

Most of the prints are simple and didactic: "Swan" (below an image of a swan): "Julius Caesar" (below image of Caesar on horse). Some are elaborate engravings of scenes from everyday life: "The storming and taking of the Bastile by the Citizens of Paris, 14th July 1789"; "Horned Cattle drawing a Dung Cart". Others are comic-strip-like satirical stories: "Prince Squeak [a Rat] gives his orders with joy, All Enemy Cats [defending Cat's Castle] to destroy". A few are humorous on the darker side: "In the cold nipping Air, Mad Tom walks in despair" (Mad Tom walking in beggars clothes); "I stand up for my due, Says old Shylock the Jew" (Shylock with balance and knife). (WW) |

David Chibbett This book is a reasonable overview of the development of printing and book illustration, with lots of information about ukiyoe schools in the second half. It barely reaches the Bakumatsu period, however, and so sheds little light on the world of art and publishing from the middle of the 19th century. It does, however, have some interesting, if few, illustrations, both of printed text and graphic illustrations. Of interest here are two black-and-white illustrations. One shows "a papermaking shop selling fans, lanterns, and color prints (nishiki) [sic], from Dainihon bussan-zue (1877), illustrated by Hiroshige III" (p. 84, fig. 24). The other shows "Koshodo, the publishing house of Tsutaya Jusaburo, from the Ehon azuma asobi (1799), illustrated by Hokusai" (p. 86, fig. 25). (WW) |

Susanne Formanek and Sepp Linhart (editors) This book features the following thirteen articles in three parts. Some of the articles are adaptations of articles that had been published in German in 1995. Others were written especially for this volume. See Written Texts - Visual Texts: A welcome book with a missing chapter on this website for my feature review of this book as published in the Number 80 (June 2006) issue of Andon. (WW) Contents

|

Furusho Tamon The band on the cover reads "Hitsu wa chikara yori tsuyoi!" [The brush is mighter than the sword!] -- the motto of both the progatonist of this novel and its creator. Sakichi writes stories that are published in kawaraban -- woodblock-printed broadside newssheets. Furusho used to be a newspaper reporter. "Furusho Tamon" is the penname of the non-fiction writer Uemae Jun'ichiro. Born in Gifu prefecture in 1934, Uemae graduated in Anglo-American Languages (Ei-Bei go ka) from Tokyo University of Foreign Languages before becoming a reporter for Asahi Shinbun. He turned free-lance in 1966 and also began writing historical mysteries, such this novel in his "Kawarabanya Series" about a kawaraban publisher in the late Edo period. In 1977, Uemae shared the 8th Oya Soichi Non-Fiction Prize for his first book, Taiheiyo no seikansha [Survivors of the Pacific], about Japanese prisoners of war who bore the stigma of being captured alive, some of whom cooperated in the production of leaflets urging Japanese to surrender. Uemae's by-line is perhaps best known to readers of the long-running "Yomu kusuri" [Reading medicine] column in the weekly Shukan bunshun -- a play on "nomu kurusi" [oral medicine]. The column ran in the magazine from 1983 to 2002, and was released in 37 volumes between 1984 and 2002. (WW) |

Milne Henderson This is an interesting effort to present a collection of preliminary drawings organized by apparent theme. Some captions, though, are flawed. The numbers in the Contents refer to plates, as there are no page numbers in the book. Drawings with Western Elements (1-32) Sumo Wresling and Kendo (22-40) Drawings of Geishas (41-86) Ronin and Samurai (87-105) Suicide (106-114) Aspects of Travelling (115-125) Drawings with Various Themes (126-144) Possibly drawn by ToshikataFrom the Introduction:

Jack Hillier and Roger Keyes were enlisted to attempt to trace the most likely artist. At the time of publication, both were in agreement that the drawings had possibly been done by Mizuno Toshikata (1866-1908), Yoshitoshi's best known student, though there was no certain proof of this. "Western" influenceThis book, like most others by self-conscious "Westerners", betrays a strong interest in "Western" influences on things "Japanese" during the Meiji period. From "The Impact of the West":

"Westernization" by "Westerners"Books like this are bound to be full of examples of how "Westerners" project their "Western understandings" on things "Japanese". Plate 114, which fills two facing pages (click on the image to enlarge), is accompanied by a caption that makes one wonder if perhaps people who believe that "Westerners" can't understand Japan might be right. |

Higuchi Hiroshi (1905-1982) (ed) This compilation, of prints from museum and private collections, is one of the most important early postwar ukiyoe reference books covering specifically late Edo and Meiji prints. The prints span roughly half a century, from the period of reform that commenced with the arrival of Perry's ships in 1853, to the demise of ukiyoe around 1897 (Higuchi's dates). The 14 pages of front matter are guides to contents, organized by subject (e.g., Meiji restoration, steamships) or genre (e.g., nishikie shinbun, mitatee). Next come 136 unnumbered sheets of glossy stock printed on one side only. The first 2 sheets show color images of 4 prints, including Anji's print of Kyobashi Matsuda, which is also featured on the cover of this volume. The other 134 sheets feature black-and-white images of 430 prints. The 94 pages of back matter consist of commentary on the subjects and genres, a fairly detailed chronology (pp 77-84), and biographical briefs on numerous late-Edo and early Meiji drawers (pp 85-94). The book is supposed to have a slip case, though the copy obtained for this review did not have one. Two glossy sheets show 8 news nishikie, including (1) one Tokyo nichinichi shinbun print by Yoshiiku (TNS-736 Kishida Ginko == Taiwan Expedition), (2) two Yubin hochi shinbun prints by Yoshitoshi (YHS-661 Rashamen == foreigner's mistress; YHS-1127 Maebara Issei == Yamaguchi rebellion), (3) four Choya shinbun prints by Yoshitoshi's student Toshinobu II (1866-1903), and (4) one Jiji shinbun supplement by Chikanobu (1838-1912). Higuchi's commentary on "nishikie shinbun" [nishikie news] fills an entire page. It's most important contribution is a citation of a contemporary Choya shinbun article which remarks on the popularity of news nishikie (Higuchi 1962:61).

This last lines echo the phrasing in the first part of Fukuzawa Yukichi's Gakumon no susume [An encouragement (A promotion, The advancement) of learning], published in parts between 1872 and 1876. The first part came out in the second month of 1872, shortly before the above article, and near the end is the line "I would call this not knowing shame, I would call this not fearing laws" (恥を知らざるとや云はん、法を恐れずとや云はん) [Iwanami Shoten bunko edition, 86th printing, 2006, page 16; translation mine]. Higuchi is probably quoting the citation of Choya shinbun from a 1925-1926 work by Miyatake Gaikotsu, who says the article appeared in the 31 March 1875 issue of the paper -- shortly before the first issues of the Hiragana eiri shinbun hit the streets (see review of Miyatake 1997). This illustrated paper, and others, effectively doomed what little interest people might have had in the news nishikie even as souvenirs (see TNS Souvenirs to News under Articles). However, Higuchi misconstrues the relationship between news nishikie and newspapers (Higuchi 1962:61).

Higuchi goes on to point out that Yoshiiku was a founder of and worker at the Tonichi, so at the time he was one of the Tonichi managers, and that he drew the news nishikie in addition to his work at the newspaper. But Higuchi provides no foundation for his claim that Yoshitoshi had any connection with the Yubin hochi. Higuchi's comment on the names of news nishikie is also misleading (Higuchi 1962:61).

This remark is the source of Meech-Pekarik's comment, in an endnote, that "Some nishiki-e shimbun arbitrarily attached the names of nonexistent newspapers" (Meech-Pekarik 1986:242, n16). The note expands remarks she made in the main text that also seem to have been inspired by Higuchi's misconstruings of the relationship between news nishikie drawers and newspapers (Ibid., 216). The problem is that Higuchi (and, following him, Meech-Pekarik) take "shinbun" to mean "newspaper" rather than "news" -- and, for him, "shinbun" is a valid name for a news nishikie only if it refers to an "actual newspaper" (honmono no shinbun). Hence his remark that nishikie with "shinbun" names that were not "real newspapers" had "abritrary" names of newspapers that didn't exist. The faults in Higuchi's overview of news nishikie stem from his lack of material of research material on Tokyo and Osaka news nishikie. He published his book nearly a quarter of a century before Ono's study of Tokyo prints (1972), and it was another twenty years before the appearance of Tsuchiya's study of Osaka prints (1995). Meech-Pakarik, though, had a decade during which to discover Ono's work. Higuchi uses "nishikie shinbun" as a general label. All he says about Osaka is that "It is reported that in Osaka there were instances in which newspaper companies themselves published nishikie shinbun" (Higuchi 1962:61). He does not consider that there might not have been any "actual newspapers" in Osaka, hence no "newspaper companies" to publish Osaka news nishikie. Ono calls Tokyo news nishikie "shinbun nishikie" and Tsuchiya calls Osaka news nishikie "nishikie shinbun" for reasons that clarify the differences in the rolls that she believes news nishikie played in these two places. Tsuchiya argues that newspapers did not yet exist in Osaka, and to some extent Osaka news nishikie served the role of newspapers in Tokyo. There was nothing arbitrary about their naming, however. They were peddled as sources of "news" -- as their names imply, for "shinbun" then meant "news" and not "newspaper" in the sense that it now refers to what Higuchi called "actual newspapers". And yet it is important to keep in mind that news nishikie were not newspapers. There is no evidence, even in Osaka, they were intended to complete with newspapers as such. In fact, most evidence, especially in Osaka, suggests that their publishers were merely using (and even abusing) the fashionability of "shinbun" in order to sell souvenir prints with stories that had more value as human interest than credibility as news. (WW) |

Jack Ronald Hillier (1912-1995) This study of art in Japanese books from the 1600s to 1951 covers artists, designers, woodblock cutters, and printers. It has over 900 illustrations, 225 of which are in color, plus a glossary, bibliography, and index of books and artists. As might be guessed from the reputation of the publisher, this heavy and pricy tome holds little interest for students of art in the more "vulgar" publications of late Edo and early Meiji periods. (WW) |

Richard Illing This book is widely viewed among English-bound ukiyoe fans as a standard and useful reference. It is, to be sure, a well-conceived overview of woodblock prints, and may well be the best introduction of its kind. It covers early prints, Harunobu and color prints, actor prints, beautiful women, landscape prints, nature studies, literature and legend, surimono and fan prints, and other styles, as well as modern prints. This will suffice until one realizes that there is a huge world of more popular, vulgar prints, including the news nishikie, that Illing, like most art historians, have studiously avoided. Illing's reference to one of Yoshitoshi's "One Hundred Views of the Moon" (plate 123, p 112) prints as an example of his continuing efforts "to produce popular broadsheets, increasing his market by designing prints which were issued as 'colour supplements' for popular newspapers" (p 161) is puzzling. It is not clear what Illing means by "broadsheet". It could not mean newspaper, since Yoshitoshi was never in the business of producing newspapers of any size. It smells more like an on-the-fly synonym for "oban", a large size of washi, which Illing dubs "standard format" in his glossary. The moon series, like most ukiyoe and nishikie published in Edo/Tokyo, was printed on oban washi, which is a bit larger than B4 paper today. In any case, the moon series, issued between 1885 and 1892, the last years of Yoshitoshi's life, was of very high quality and would not have been distributed by newspapers as supplements, but sold for a good profit at local book and print shops. A few pages at the end of this book -- on collecting, examples of signatures, date and censor seals, and a glossary -- are intended for newcomers interested in print details and collecting. Seasoned dealers and collectors, and serious researchers, will not find the one page of signatures, and the one page of seals, particularly useful. But before he nodded, even Homer began somewhere. And all things said, this book is not a bad place to start. (WW) |

Ishii Kendō Forthcoming. See "Seal of approval and date of print" section of Typical print details for scan of Ishii's images of aratamein used from Meiji 5 to Meiji 8 (1872-1875). |

Ishii Kendō Forthcoming. |

Itabashi Kuritsu Bijutsukan (Itabashi Art Museum) The arrival in Japan in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, of Portuguese, Dutch, English, and other Europeans as traders and missionaries, had an inevitable impact on Japanese science and art, as well as the politics of the Edo period (1603-1868), during which most of Japan was ruled by the Tokugawa clan. The political solution to the threat to Tokugawa power, partly posed by Christian factionalism in the southwestern provinces most exposed to the arrival of Europeans sailing from Southeast Asia and China, was to ban Christianity and limit commercial activities to Dutch which were more interested in trade than religion. The result was an influx of Dutch learning (Rangaku), Dutch drawing (Ranga), and other things related to Holland (Oranda). The main interest of this catalog for students of news nishikie are two paintings of cherubs, one by Ishikawa Tairo (1765-1817), a hatamoto samurai who painted in Dutch style, the other his older brother Ishikawa Moko (1763-1827). Also of interest are the engravings at the very end, showing a variety of unfurled banners used as titles, one borne by a pair of cherubs. The cherubs in one of Ishikawa Tairo's paintings (Exhibit 100, page 45) are strikingly reminiscent of the putti on Tokyo nichinichi shinbun nishikie mastheads. The work is signed "Tafel Berg" -- Ishikawa's Dutch name -- reflecting also "Tairo" (大浪), from the Chinese name (大浪山) of Table Mountain in Cape Town. (WW) See TNS two series, four stages and Cherubs and banners for more than you ever wanted to know about these topics. |

Gustav Kobbe This article, which contains 17 pictures, 6 of which are full page tinted sepia with a full page of text about the picture on the back, proved to be a dead end. There were no examples of cherubs holding unfurled banners bearing glad tidings, map legends, or newspaper titles. What inspired Yoshiiku to employ cherubs in his design of the Tokyo nichinichi shinbun nishikie remains a mystery. The point I would make here is that, when attempting to solve such mysteries, negative results are also valuable, as in science. Not until purchasing this item for twenty dollars, and waiting for its arrival in the mail, could I rule it out as a possible lead. (WW) |

Koshi Koichi This is a study of illustrations in early Mediterranean and European manuscripts. The manuscripts range from the Greek and Roman classics to biblical literature. The illustrations depict war, bullfights, suicide, and other themes. There are ample citation notes and illustrations. The illustrations are fully attributed and are also listed in a detailed chronology that spans the 8th century BC to the 15th century AD. (WW) |

Helen Merritt and Nanako Yamada This book is the only extensive survey in English of woodblock kuchie (lit. "mouth drawings") -- a generic term for any (not only woodblock) frontispiece illustration. Woodblock kuchie, typically foldouts tipped or bound in the front of a book or magazine, were popular during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Unfortunately, as objects of collection, they are usually found separated from their original volumes, from which they have taken for archiving or framing. The book is a mixed bag, arguably more reliable about art and literature, than about society and behavior. The historical, social, and psychological commentary is mostly warmed-over Japanology along the lines of "the Japanese" this and "Westerners" that -- which serious students of the human condition will want to take with a grain of salt. For collectors and dealers who depend on English, the book's most useful features are the appendices containing Biographical Sketches of 43 artists and Facsimile Signatures and Seals of 36 artists. This many artists are represented by only 80 illustrations -- 41 larger images in color, and 39 smaller ones in black-and-white. A book like this, more about art than of art, would have been more useful if a larger font had been used with less space on fewer thinner pages, to make room for lists of known kuchie by source and/or artist with panels of thumbnail images. Of interest to news nishikie fans are the biographical sketches of Kaburaki Kiyokata (at 3 pages, the longest) and Mizuno Toshikata (at 2 pages, the third longest). Kiyokata is correctly identified as Kaburaki Ken'ichi, the son of Jono Saigiku (Jono Denpei, Sansantei Arindo), one of the founders of Tokyo nichinichi shinbun and the main inspiration behind Yamato shinbun. It is also true that Ken'ichi was apprenticed to Toshikata, who worked as an illustrator for Yamato shinbun, and that Toshikata, as his name implies, was a disciple of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi. But the authors fail to make the link between Yoshitoshi and Jono, and in turn Ken'ichi. Yoshitoshi and Jono had known each other and collaborated as drawer and writer for at least two decades by the time Ken'ichi took an interest in art. Yoshitoshi had drawn a popular series of prints called Kinsei jinbutsu shi for Jono, who wrote the stories on the prints, which he distributed as monthly supplements of his newspaper. So Yoshitoshi was the big-name draw for the paper, and it was mainly his presence in Jono's life that inspired the young Ken'ichi to want to be a drawer. Only because of Yoshitoshi's failing health did Jono's son become a student of Toshikata and adopt the name Kiyokata. (WW) |

Nagata Seiji This book is a study of resources about the social and economic climate of woodblock prints in Japan during the late Tokugawa and early Meiji periods, usually referred to as "kindai" (recent, early-modern, pre-modern times) as opposed to "gendai" (present, modern times). Practically nothing is known about the conditions that prevailed in the woodblock industry or market until ukiyoe began getting lots of attention as objects of art, outside and then inside Japan, from the late 1880s. Most of what little is known is based on a handful of contemporary accounts, and on a few early 20th century (particulary Taisho) reminiscences by people old enough to remember the last half of the 19th century. Yoshiiku and Kawanabe as collectorsBut several things are clear. A number of people who have left their names in Edo history collected woodblock prints. A couple of prints in overseas museums bear the owner's seal of Ota Nanpo (1749-1823), a samurai official who wrote comic poems and gesaku stories. Santo Kyoden (1761-1816), another gesaku writer as well as a drawer, and Ryutei Tanehiko (1783-1842), the most famous gesaku writer, also left evidence that they were print collectors. Nagata also writes this (p 16).

Nagata traces the history of collection by foreigners in Japan back to Isaac Titsingh (1745-1812), a director of the Dutch East India Company in Japan, who made two trips to Edo. A catalog published in 1819, of belongings he left when he died, lists two paintings and eight woodblock prints he acquired while in Japan. There were probably others before him, and the numbers of collectors keep increasing. Nagata is of the opinion that Dutch and other foreign collectors at the time, even the German physician Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796-1866), saw woodblock prints through pretty much the same anthropological eyes as their Japanese counterparts. It was not, he says, until the end of the 1850s and into the 1860s that ukiyoe began to be greeted in Europe as fine art peculiar to Japan (p 23). Kuniyoshi and Yoshitoshi

|

|

At this time nishikie of the likes of Sharaku or Utamaro were not much welcome and when night fell before [the premises of the publisher] Suharaya in Kuramae [in Asakusa], an old-book dealer [furuhon'ya] who was a monk who had set up a shop was selling them for about one-sen each, but even then there weren't many people buying, and new prints by Kuniyoshi and Yoshitoshi and the like were more welcome. |

Awashima goes on to say that "it was an age when no one would make a fuss if you sold erotic books [waraie] on the main street. In the old-book dealer's shop, on the edge of Asakusa Mitsuke where [criminals / heads] were put on display, were famous rice cakes." He often saw such things in the shops that would put out old books by the well in front of the house [of the shop]. There were gamblers, he said, and they'd hustle the country folk who came to look at [the books] and empty their purses right there on the street.

Nagata is just warming up. He gets very serious when it comes to showing how contemporary collectors went about finding prints, how much they paid, and all the rest. Everything began to change in the Meiji period, especially after Europeans, of the opinion that they had discovered "art" in Japan, began shipping off entire collections. Then locals formed ukiyoe societies. Print shops began to produce catalogs. Nagata copiously sites and even illustrates such materials.

Mr. M's memoranda

Nagata uses contemporary sources to examine the plight of woodblock book and print publishers from mid to late Meiji, roughly from the late 1880s to the first decade of the 1900s. The woodblock publishing associations were forced to reorganize and eventually had to join the general publication unions that emerged. Woodblock publishers who didn't quickly innovate and adapt were unable to compete with the new copperplate, lithograph, lead type, and photogravure technologies that enabled mass printing at much lower costs, and simply went out of business.

The centerpiece of Nagata's study, for our purposes, is a chapter called "The movements of woodblock publishers [hanmoto] from the middle to the end of the Meiji period (from Mr. M's memos)". The chapter runs nine pages (32-40), eight of which are given to citations of memoranda attributed to the mysterious "Mr. M" -- who Nagata descibes as someone who amassed a large collection from the late 1880s to the mid 1910s and also published. Mr. M's family allowed Nagata to transcribe and publish the notes on the condition he not reveal their writer's name.

Gekko, Yoshitoshi, and Fukuda

The memoranda contain an enormous amount of detail concerning publishers, artisans, their working relationships, technology, compensation, management, the market -- not general comments, but specific times, places, names, amounts.

In Item 6, dated 1889/1890, Mr. M. writes that he began buying Gekko's Gekko Zuihitsu [Gekko sketches] and Yoshitoshi's Tsukihyakushi [One-hundred views of the moon], among others. He then lists a number of print publishers by their general address -- including "Ningyochodori, Fukuda" -- otherwise known as Gusokuya (p 33).

Item 7 follows up the list of publishers in Item 6 with a list of publishers and the drawers whose prints Mr. M recalls they were publishing at the time (p 33).

|

(7) [Meiji 22, 23] [1889/1890] Sasaki and Takekawa [are doing] Gekko prints [Gekko mono]. Akiyama, Yoshitoshi. Sawamura, Kyosai and Kiyochika. Fukuda, Yoshiiku and Kunichika and Chikanobu. Hasegawa, Kunichika and Chikanobu. |

Fact wise, this looks okay. As early as 1887, Takekawa Risaburo was publishing Gekko zuihitsu prints designed by Ogata Gekko (1859-1920). Akiyama Buemon was publishing Tsuki hyakushi prints from 1886. And Fukuda Kumajiro, the third generation Gusokuya, was publishing some of the few prints Yoshiiku was designing in the late 1880s. Fukuda also published Yoshiiku's Tokyo nichinichi shinbun nishikie (1874-1875), Kunichika's Tokyo kakushu shinbun triptychs (1876), and Yoshimura's Tokyo nichinichi shinbun triptychs (1876).

Fukuda, Yoshiiku, and Tonichi supplements

Having introduced the publishers by location (Item 6), then by drawer (Item 7), Nagata gives a few sections to gossip about selected publishers. Item 11 is devoted to Fukuda (Item 34-35).

|

(11) Fukuda's father (present [Fukuda] is adopted son, who was 25, 26 around [Meiji] 40 [1897]) liked the theater and published many actor pictures [yakushae]. It is said that [on the occasion of] the hundredth performance of Danjuro, [Fukuda] took a preliminary drawing by Kunichika to Danjuro for his inspection, and [Danjiro] had been carrying a Fudo Myoo [Acalanatha, god of fire] costume [funso] and others things and lost it backstage [gakuya]. When [Fukuda] asked [Kunichika] to again do a preliminary drawing saying [the first one] had been extremely well done [Kunichika] refused saying he wouldn't do the same thing a second time. [Fukuda] was extremely worried about the publishing of the Tokyo nichinichi shinbun picture supplements drawn by Yoshiiku. |

Fukuda turns to picture postcards

Immediately after this Mr. M remarks that, during the Meiji period (although he's been talking about the Meiji period all along), all publishing shops [shuppanten] competed in putting out many Sino-Japanese War prints [Nisshin Senso ga]. But they published too many, unsold prints piled up, and a lot of small publishing shops went out of buisness. He also writes that fewer people sought nishikie, while lithography and photogravure became more popular.

Mr. M concludes his item on Fukuda with this very interesting observation (p 35).

|

And when it came to actor pictures, [publishers] were pressured on account of picture postcards and photographs, and among publishers [shuppansha] and of course [sara ni nashi] publishing shops [shuppanten], Fukuda started a postcard shop, Takekawa and Yokoyama started round fan shops [uchiwaya], and even Akiyama did postcard sales and publishing on the side, and though actor picture drawers [like] Kunichika and [ellipsis] after [him?] Chikanobu and Kiyotada [ellipsis] [drew actors] [publishers] did not put out [their pictures] as nishikie. |

Fukuda ranks low among publishers

In Item 12, Mr. M ranks sixteen publishers according to the amount of prints they are publishing, in a note headed 1889, 1890, and indicates their quality in parentheses (p 35).

1. Marutetsu (high) 2. Sasaki (high) 3. Fukuda (middle) 4. Akiyama (high) 5. Sawamura (middle high) 6. Takekawa (high) 7. Taihei (high) 8. Yorozumago (high) 9. Kiyomizuya (middle) 10. Tunashima (high) 11. Matsui (high middle) 12. Moriki (middle) 13. Hara (middle) 14. Yokoyama (middle high) 15. Kodama (middle) 16. Ueno (middle)

Mr. M has four ranks -- high (7), middle high (2), high middle (1), and middle (6). Fukuda is among the six ranked at the bottom.

Yoshitoshi mad but not arrogant

To be continued (WW)

Amy Reigle Newland (editor) From Hotei's website:

What this means is that, for Euro 68.50, you will be buying a "conference book" -- in other words, a mixed bag. Here is what is in the bag.

The back matter includes a Chronology, Glossary, easy to read Index, and sixteen pages of Colour Plates. The geography of nishikie commerceMatthi Forrer's "The Relationship Between Publishers and Print Formats in the Edo Period" (pp 171-205) is the most interesting article in this book in terms of understanding the commercial aspects of nishikie publishing. Though Forrer's study "concerns the work of only a few designers from 1765 until the 1850s" it sheds light on the social geography of nishikie as a commodity. Forrer investigated "the print formats used by a few select print designers and the relationship between them and their publishers" in order to reveal "the composition of the audience for prints" (p 187).

Forrer examined the works of Harunobu, Kiyonaga, Utamaro, Eisen, and Hiroshige by publisher, and found the following pattern in the relationship between publisher location and type of publication in the case of Hiroshige's Edo meisho [Edo famous places] series (p 185).

Forrer arrives at this concludion about Hiroshige (p 188).

Such analyses of nishikie as objects in the economic lives of producers, sellers, and consumers is in much too short supply in a field dominated by more esoteric concerns about nishikie as "art" appreciated by present-day academtics and collectors. Yet there is something missing here. Of course publishers who sold directly from their print shops would want to be located in places frequented by the people who would be most likely to buy their publications. But prints are light and easily bundled and transported, over land or by water, to other points of sale. Forrer might have said more about the role of distributors and itinerant vendors. In any case, the roads taken into and out of Tokyo in the early years of the Meiji era were essentially the same as those described by Forrer for Edo during the period of his study. And the neighborhoods of early Tokyo were not that different from those of late Edo. So how did the locations of news nishikie publishers affect their sales? (WW) |

Ryoji Kumata This small book, with 20 pages of color plates in front and numerous black and white plates elsewhere, presents a broad survey of Meiji woodblock prints in 24 short topical chapters. Of interest here is a three-page chapter called "Eiri shinbun no hajime" [The beginning of illustrated news] (pp 62-64), in which Ryoji depicts and introduces four news nishikie. Ryoji calls Tokyo nichinichi shinbun (TNS) and Yubin hochi shinbun (YHS) news nishikie the first "nishikie no eiri shinbun" [nishikie news with illustrations]. He introduces TNS No. 1 (Itinerant priest murders and robs loyal wife) and remarks that he has 40 to 50 prints like in the TNS series. He then introduces TNS No. 813 (Man marries man who has been raised as woman), remarks that such stories are taken up on television today, and observes that not much has changed in society past and present, even with respect to the way such stories are reported as oddities. Ryoji goes on to show and summarize the stories in Nishikiga hyakuji shinbun No. 20 (Woman jumps into river unable to meet her sailor lover) and No. 22 (Man sneaks into second story of tofu shop). There are also chapters on copperplate prints, lithographs, and postcards. (WW) |

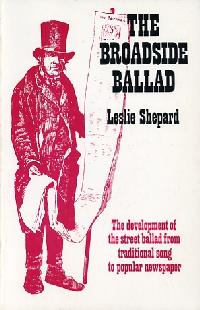

Leslie Shepard This is the most widely published and most interesting book by Shepard on "The development of the street ballad from traditional song to popular newspaper" as the cover blurb explains. It is illustrated with over 60 facsimiles in the form of black-and-white photographs, diagrams, and line drawings. The 1978 edition shown here is the first American edition of the first British edition published in London by Herbert Jenkins in 1962. (WW) |

Leslie Shepard "This book is not intended to be a conventional history, with copious footnotes, every detail discussed to death, and all the reader's work done by the author," Shepard writes at the start of his preface (p 9). Scholarship is like make-up, the effects of which are destroyed if you can see it. All we can see are the effects of Shepard's scholarship. As the Preface continues, "Folklore, from which street literature developed, is essentially a shared experience, falsified by over-detachment or too much scholarly apparatus, and much of this story can only be told by implication." Shepard's implications are mostly showing facsimilies of street literature and letting it speak for itself -- literally, since broadsides of tales and gossip and news, though written, were also recited and even sung. The frontispiece (click of image of title page to see a larger scan) of what I would guess is a 18th (possibly late 17th or early 19th century) woodcut of a ballad monger. Several other images of street vendors who hawked news and other printed ephemera are shown in a chapter dedicated to "Pedlars and Patterers". The Contents are as follows: 1. The Varieties of Street Literature 2. How It Began 3. Printers and Publishers 4. Pedlars and Patterers 5. The Influence of Street Literature 6. Survivals 7. Examples and Notes The Pepys CollectionSamuel Pepys (1633-1703), the British civil servant and diarist, acquired broadside ballads that had originally been collected by a certain John Selden. Pepys built this collection into what remains the "largest and most complete of its kind" with "some eighteen hundred broadside ballands" (pp 31-31). In a five-volume compilation he published in his own time, Pepys arranged the ballads under the following ten headings (p 31). 1. Devotion and Morality 2. History -- True and Fabulous 3. Tragedy -- viz[t] Murd.[rs] Execut.[ns] Judgm.[ts] of God 4. State and Times 5. Love -- Pleasant 6. do. -- Unfortunate 7. Marriage, Cuckoldry, &c. 8. Sea -- Love, Gallantry, & Actions 9. Drinking & Good Fellowshipp 10. Humour, Frollicks &c. mixt. "On the verso of the title-page he [Pepys] quotes Selden's famous statement:" (pp 31-32)

Broadside balladsAll manner of newsy stories were told in entertaining verse, with woodcut illustrations, in broadsides and newspapers. Whereas many writers conflate "broadsides" with "broadsheets" and speak only of the latter, Shepard carefully differentiates these two forms of publications. Shepard's Glossary makes this distinction (p 224).

So kawaraban and other single-sheet woodblock printed matter in Japan are "broadsides" rather than "broadsheets". The Appendix consists of a facsimile of an eight-page 1832 "Catalogue of Songs and Song Books, Sheets, Half-Sheets, Christmas Carols, Children's Books, &c, &c, &c, Printed and Published by J. Catnach, Printer and Publisher." Shepard introduces the catalog with a description of the Catnach family, one of the most producive publishers of street literature in London, and gave this example of how many copies of a news ballad its presses could run off when pressed (p 215).

Sale of a WifeHere are the first and final of the 23 stanzas of Sale of a Wife. While some broadsides showed stories in verse form, this one presents a continuous text, with capital letters and punctation marks to delimit the couplets and quatrains. I have rearranged the text in verse form, but preserved the original case and puncutation. (Song 221, Page 177)

Shepard's note on this ballad provides just the right amount of commentary (p 208).

Shepard has written several books on broadside ballads and their printers. This one is social history at its best. (WW) |

Shimonaka Kunihiko (compiler) 1. Meiji 2. Taisho: Historical novels 3. Taisho: Modern novels 4. Showa prewar: Juvenile novels 5. Showa prewar: Historical novels 6. Showa prewar: Modern novels 7. Showa prewar: War novels 8. Showa prewar: Mystery and suspense novels 9. Showa postwar: Historical novels 10. Showa postwar: Modern novels This set presents all kinds of illustrations in popular fiction and other literature from the Meiji period through the early postwar Showa period. Each volume contains about 130 black-and-white and 20 color pages. The first two-thirds of each volume feature page after page of illustrations with captions. The last one-third contains illustrated articles by various scholars. "Sashie" (inserted drawings) refers to any illustration, usually hand-drawn, that accompanies the text of a story, fictional or otherwise. Broadly speaking, however, sashie could be any illustration that is "inserted" into a publication, including quite commonly "kuchie" (frontispiece) prints, and less commonly looseleaf prints that accompany a publication as a "furoku" (supplement). As titles of the volumes suggest, sashie are typically associated with fiction. Many newspapers and magazines in Japan today continue to feature serialized novels or short stories. They still commission sashie drawers to illustrate the fictional action, and the illustrator is usually credited alongside the author's byline. Volume 1 leads off with news nishikie by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892), Morikawa Chikushige (dates unknown), and Ochiai Yoshiiku (1833-1904), all three of whom also illustrated books, magazines, and newspapers. Next come Takeuchi Keishu (1861-1943), Kawanabe Kyosai (1831-1889), Kajita Hanko (1870-1917), Mizuno Toshikata (1866-1908), Suzuki Kason (1860-1919), Kaburagi (sic) Kiyokata (1878-1972), and Kobayashi Eitaku (1843-1890), and seven other drawers, most of whom are best known for the kuchie they drew for popular novels and magazines. Of this second group. All such drawers drew their share of conventional sashie for books, newspapers, and magazines. Of particular interest here is Kobayashi Eitaku, who drew the Kakushu shinbun zukai no uchi news nishikie series written by Tentendo. Volume 1 shows, unfortunately not in color, Eitaku's famous "Hatamoto wife searches for fallen husband" nishikie illustrating a story reported in Enkin shinbun (Number 27, Keio 4-5-30 = 1868-7-19). See Eitaku's Shogitai for a translation and disucssion of this print, and for commentary on Eitaku's life and art. (WW) |

Suzuki Jin'ichi Suzuki, an art historian, has divided his small but informative book into three chapters. 1. The start of the opposition to bakufu (The quickening power of townsmen) Chapter 2 is particularly interesting because Suzuki argues that ukiyoe generally become a vehicle for journalism in the broadest sense of the word. His thesis that ukiyoe become "journalistic" in the late Edo and early Meiji periods is not predicated on the rise and fall of news nishikie, a relatively minor development in the history of late-period ukiyoe. Rather he argues that woodblock publishers found it more profitable to put out prints that conveyed information related to the times, and turned popular writers and drawers into commodities. Midway through his "form and structure" introduction to Chapter 2, Suzuki makes this general observation (p 39).

To further support his thesis that ukiyoe turned journalistic [jaanarisutikku], Suzuki devotes many pages to the content of, and expression in, late-period ukiyoe. He describes and analyzes content and expression under several thematic headings: politics, economics, diplomacy and communications, society, propaganda and publicity, and entertainment reading. Here, as in the introduction, Suzuki draws examples from all genres of ukiyoe, except news nishikie. Suzuki wraps up his discussion of themes as follows (p 66).

Suzuki devotes the final four pages of Chapter 2 to the advent of news nishikie and other examples of how woodblock publishers, drawers, and writers came to be closely associated with the development of newspaper journalism. His overview, though general, is commendable because he saves it for the end, as frosting on his cake. "I don't think one can discuss Japanese newspaper history," he says in conclusion to Chapter 2, "without acknowledging the ukiyoe journalism [ukiyoe jaanarizumu] that made free use of woodblock print media" (p 70). (WW) |

Takahashi Katsuhiko Takahashi flaunts his usual stuff as he delves into the stories behind the stories in an incredible variety of ukiyoe prints spanning the late Edo and early Meiji periods. Sparsely illustrated with black-and-white pictures, it includes three short sections on news nishikie, each of which makes a few general observations about the genre then explores a single print. The three prints whose stories he finds especially intriguing are: Tokyo nichinichi shinbun (Number 933) Tokyo nichinichi shinbun (Number 697) Yubin hochi shinbun (Number 532) Fifteen years after writing this book, Takahashi incorporated the world of news nishikie, and the gruesome homicide depicted in TNS-933, into an episode in the fourth volume of his popular Kanshiro hirome tebikae [Kanshiro promotion notes] historical mystery (Shosetsu subaru, June 2005, pp 364-369). In the first volume, Kanshiro is introduced as a disenfranchised samurai who becomes a publicist along the lines of a present-day advertising agent, and is tight with social outlaws like the gesaku writer Kanagaki Robun. (WW) |

Takahashi Katsuhiko In this nicely illustrated book, Takahashi argues that ukiyoe, which devloped and flourished during the Edo period, were more than just artistic drawings, but also constituted a new medium for conveying news, advertising, and entertainment. Takahashi takes the reader on a tour-d-force of Edo art history, from the incredible perspectives drawn by Okamura Masanobu (1689-1756) in the 18th century, to Yoshiiku's Tokyo nichinichi shinbun nishikie and a bit beyond. (WW) |

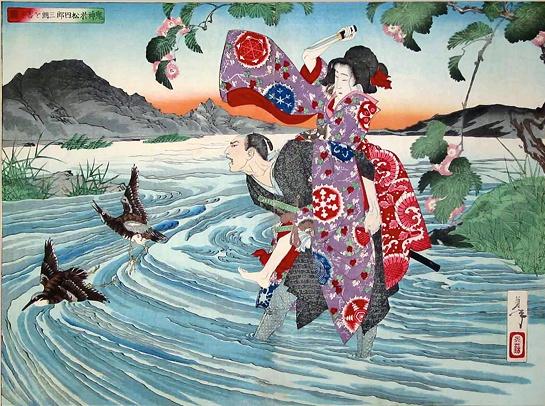

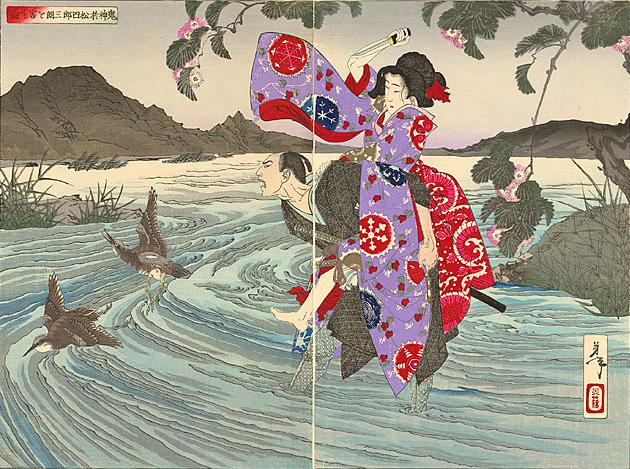

Tanaka Yuko This book is listed here because it introduces Suzuki Harunobu's "Shimizu no butai yori tobu bijin" [Beauty jumping from a stage in Shimizu], both on the cover and in the text (p 99). The picture supports Tanaka's contention that Harunobu, who is credited with developing the colorful nishikie style of ukiyoe, abandoned conventional actor and courtesan prints in favor of "mitatee" (analog drawings), which she defines as a "haikuization" of the classics (p 97). Mitatee were parodies of episodes in classical literature, in which historical figures or fictional characters were comically depicted in a contemporary setting. Two famous warriors engaged in a famous battle, for example, might be transformed into geisha who are posed or otherwise featured so as to resemble the warriors in battle. Such humorous works often fed on each other. Tanaka finds mitatee, most of which were based on the classical world, and not real life or actors or courtesans, difficult to call ukiyoe. "Moreover," she says, "by imposing the world of the classics on young urban boys and girls with a delicacy that would arouse practically no feelings of flesh or sex, Harunobu's drawings leapt from the ground, defied gravity, drifted in a surrealistic weightless world" (p 97). Tanaka captions a thumbnail black-and-white picture of "Jumping beauty" as follows (p 99).

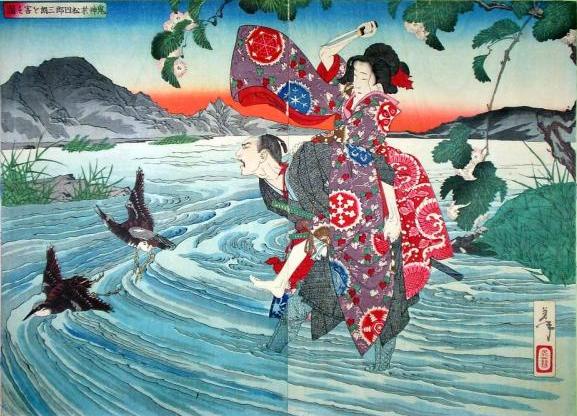

Tanaka observes that "Jumping beauty" is not a mitatee but an "egoromi" (picture calendar). She points out that characters for "big, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 10" are hidden in the seashells that are drawn on the girl's clothing. And like most art historians, she claims that Nishikie originated from the production of such picture calendars. "Jumping beauty" is said to have inspired later designs of prints showing women leaping into the sea. The most famous such print is Yoshitoshi's depiction of Chikako plunging into the snowy Asano river after failing to get her father, the wealthy merchant Zeniya Gohei (1773-1852), released from prison. He and his son were arrested after they had contaminated a Kanazawa lagoon with lime, causing the deaths of fish and a fishermen who had eaten one of the fish. (WW) |

Barry Till バリー=ティル News nishikie have been introduced in several general exhibitions of Japanese "art" outside Japan. The exhibition of Meiji "arts" held at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria in 1995 included a number of news nishikie. The English section of the trilingual catalog included the following paragraphs under the heading "Prints Used as Newspaper Illustrations" (pages 25-26).

CommentaryThe above descriptions and explanations are typically inaccurate and skewed. Yokohama mainichi shinbunIt is true that Yokohama mainichi shinbun, generally considered to have been the first daily newspaper in Japanese, was founded in Yokohama in 1870. It is also true that, in 1879, the paper was moved to Tokyo and renamed Tokyo Yokoyama mainichi shinbun. However, Tokyo nichinichi shinbun, Tokyo's first daily paper, and Yubin hochi shinbun, began publishing in 1872. By 1879, the circulations of these two papers greatly exceeded that the new arrival from Yokohama. Tokyo Yokohama mainichi shinbun was renamed Mainichi shinbun in 1886, which was renamed Tokyo mainichi shinbun in 1906. The paper was bought out by, and absorbed into, Hochi shinbun (formerly "Yubin hochi shinbun") in 1909. Today's Mainichi shinbun is unrelated to the paper that originated in Yokohama and moved to Tokyo. Its roots go back to Osaka mainichi shinbun and Tokyo nichinichi shinbun. Meiyo shinbunMeiyo shinbun was not a newspaper but a series of woodblock prints published in 1874 and 1875. The prints depicted heroes of the civil unrest that led to the downfall of the Tokugawa shogunate. The series was renamed -- and is better known as -- Meiyo shindan. See Meiyo shinbun / shindan: New tidings / stories of honor and glory for details. News nishikieYubin hochi shinbun (YHS) was the name of a series of woodblock prints, drawn by Yoshitoshi, depicting stories that had run in the newspaper of the same name. Similarly, Tokyo nichinichi shinbun (TNS) was the name of a series of woodblock prints, drawn by Yoshiiku, depicting stories that had appeared in the newspaper of the same name. Yoshiiku's TNS series began before Yoshitoshi's YHS series and amounted to nearly twice as many prints. Typical of such overviews of Meiji "art" in English, however, Yoshiiku is underplayed. Yoshiiku and Yoshitoshi were commissioned by woodblock print publishers, not by newspapers, to produce series of prints based on newspaper stories. Most such news nishikie were not newspaper supplements. Whether news nishikie were printed in especially "large numbers" is not clear. Both Yoshiiku and Yoshitoshi were commissioned to draw such prints because they were already famous. To what extent these prints became an "important source of income" is not clear. Both men were engaged in other drawing projects. While the news-related prints did their reputations and pocketbooks no harm, the series were very short lived. Drawings as illustrationsWhile some newspaper stories were illustrated with embedded woodcuts, TNS, YHS, and other news-related nishikie series were not newspapers, nor were they newspaper illustrations. There is no evidence that photography replaced woodblock prints as methods of newspaper illustration. The earliest newspapers, which were printed with woodblocks, were illustrated by woodcuts. As were used to illustrate earlier newspapers, which were printed with woodblocks and even movable wooden type. As papers came to be printed with presses using movable metal type, engraved drawings replaced woodcut drawings. While true that photographs came to replace drawings as illustrations of news stories, drawings remained -- and remain even today -- the standard method of illustrating serialized fiction in both newspapers and magazines. And drawings continue to be used to illustrate reports of trials in courts of law and other venues where cameras have not been allowed. Women as culprits and victimsMost "notorious crimes" involved either men killing women or women killing men. So what is the point of the observation that "many of [the most notorious crimes of the period] involved women as murderesses or victims of murder"? Exhibited news nishikieThe catalog includes the following prints under the heading "Newspaper Prints" (page 169). I have listed only the plate numbers and titles, as given in the catalog, following my own identifications in brackets.

The attributions and descriptions are haphazard when not wrong. Only one of the prints (TNS-748) is identified by number. The two TNS prints are attributed to "Utagawa Yoshiiku" and "Utagawa Toshiiku" -- though Yoshiiku did not go by "Utagawa" and he was never "Toshiiku". TNS-656 and TNS-747 are signed respectively Keisai Yoshiiku and Ikkeisai Yoshiiku. Among the listed prints, only those in the TNS and YHS series were news nishikie. And only the prints the KJS (Kinsei jinbutsu shi) series were newspaper supplements. Some other names, and descriptive titles, are also mangled. For example, "Takanawa" becomes "Takamawa" in the English and French titles of Kawabata Gyokusho's 高縄帰車 or "Takanawa kaeriguruma" (plate 1.12). The print shows exactly what its Japanese title states -- not "Takamawa Train Station" ("Gare de Takamawa") but a train returning on the stretch of track through the scenic Takanawa area along Tokyo bay. Kosome and Fukuchi portraitsOf interest to students of portrait nishikie, the color section of the catalog includes Adachi Ginko's Kosome (1.G Picture of Modern Japanese Woman in Western Dress in the "Kokon meifu no kagami" series and Kobayashi Kiyochika's Fukuchi Gen'ichiro (1.J Fukuchi Gen'ichiro) in the "Kyodo risshi no motoi" series. French and Japanese versionsThe French version appears to be a direct translation of the English. The Japanese version significantly departs from the English and French versions. For example, the French version of "like the Meiyo Shimbun (Illustrious Newspaper) and the Yubin Hochi Shimbun (The Postal News)" is "comme le Meiyo Shimbun (journal illustre) et le Yubin Hochi Shimbun (les nouvelles des Postes)" (page 45) -- while the Japanese version has only "Yūbin hōchi shinbun nado" [Yubin hochi shinbun et cetera] (page 66). The French version of "murderesses or victims of murder" is "meurtrières ou victimes de meurtres" whereas the Japanese has "higaisha, yoōgisha" [victims, suspects]. The Japanese term for English "Newspaper Illustrations" and French "illustrations dans les journaux" is "Shinbun no sashie" [pictures embedded in news [papers]" -- which clearly shows that the writers did not understand news nishikie as commodities apart from contemporary newspapers. (WW) |

Tomizawa Tatsuzo This books is like old wine in a new bottle -- which is better than new wine in an old bottle. It's main value is the wealth of detail it presents in a highly organized manner about late Edo nishikie featuring catfish and measles. It is also useful as digest and synthesis of over seven decades of scholarship on the "journalismization" (jaanarizumuka) of woodblock pictures in Japan -- going back to the 1930s when Suzuki Jin'ichi first used this expression (see review of Suzuki's seminal work on late-period ukiyoe drawers elsewhere in this Bibliography). Young disciple of an old schoolTomizawa Tatsuzo is a young veteran (born in 1967, doctored in 1999) of a seasoned academic world concerned with the "news value" of late Edo and early Meiji woodblock prints. A specialist in early modern Japanese history, and materials related to history and folklore, he has published several articles on two well-known genres of woodblock prints -- "namazue" (catfish pictures) and "hashikae" (measles pictures) -- which are what this book is mostly about. As Tomizawa states in the afterword, the book is a heavily revamped version of his doctoral dissertation, Bakumatsu nishikie fushiga no kenkyu [A study of late Edo nishikie satirical drawings], accepted at Kanagawa University in 1999. While mainly about nishikie featuring stories about earthquake-causing catfish and measles, it also covers other genres of late Edo prints that relate to "current events" -- like foreigners in the country and the deaths of popular actors. Tomizawa is squarely in the "birth of news" school that mounted an exhibition and published a book and CD-ROM by this name (all reviewed in this Bibliography). He authored "Nishikie no nyuususei: Namazue, hashikae, Boshin senso ki no fushiga o megutte" [The newsness of nishikie: Centering on catfish picctures, measles pictures, and satirical drawings of the Boshin war period] (pp 192-203) in Nyuusu no tanjo [The birth of news] (Kinoshita and Yoshimi 1999). Nishikie no chikara, the book under review, follows essentially the same line of argument set down in this article. In fact, it takes its title from a subhead of the article, though in the subhead "chikara" [power] is typographically stressed. The "power" in the title alludes to the ability of nishikie to ease people's minds and lives by providing them with information about matters of current concern. Of particular concern were earthquakes and measles -- following the Ansei quake that devastated parts of Edo in 1855, and an outbreak of measles in Edo in 1862 -- with advice about how to deal with such matters. Tomizawa, also in 1999, collaborated with Yoshimi Shun'ya in the planning and construction of an image database of the kawaraban and nishikie shinbun in the Ono Collection at the Institute of Socio-Information and Communication Studies at the University of Tokyo. Their work is described in Yoshimi Shun'ya and Tomizawa Tatsuzo, "Kawaraban, nishikie shinbun shiryo no gazo deetabeesu ka: Shakai Joho Kenkyujo Ono Hideo Korekushon ni kan suru sagyo no kiroku" (Construction of Visual Database of Kawaraban and Nishikieshinbunin the Ono-Collection), in Tokyo Daigaku Shakai Joho Kenkyujo sosa kenkyu kiyo (The Research Bulletin of the Institute of Socio-Information and Communication Studies, the University of Tokyo), No. 13, 1999, pages 97-116]. Nothing new as information theoryTomizawa's book therefore fits very comforatbly into the growing body of literature that concerns itself with the "birth of news" and the development of "visual news media" in mid-19th century Japan. It does not pioneer new paths so much as straighten and smooth the going on well-trekked trails that go back to the early Showa period and even late Taisho periods, when academic travels into the emergence of journalistic wookblock prints began in earnest. Tomizawa's main contribution is to organize and analyize certain genres of nishikie in ways that make it easier to navigate the terrain of late Edo society in terms of how people responded to, for example, earthquakes and measles, and the deaths of famous kabuki actors. When it comes to the early Meiji development of news nishikie, however, Tomizawa defers to the already orthodox views of Tsuchiya Reiko and others of the same "birth of news" school of historical media studies. The new bottle into which Tomizawa puts his old wine has a trendy new label -- "jiji nishikie" -- which he attributes to Sato Kenji. Between 1996 and 1999, Tomizawa partipated in the "Kawaraban / shinbun nishikie kenkyukai" at the University of Tokyo, when the "birth of news" project was launched. Sato, also a member, often spoke of "jijie" [current event pictures] and "jiji nishikie" [current event color woodblock pictures] in a presentation of "Bakumatsu-Ishin-ki no jiji-fushiteki-na nishikie gun" [Groups of current-event-satirical nishikie of late Edo and early Meiji times]. In both of his articles in Nyuusu no tanjo, Sato contributed more than others to what I would call the "terminology" debate. Sato most cogently discusses "news" as something which empowers people with information about social and political incidents and events such as earthquakes, measles, wars, or murders. In what amounts to a dynamic "information theory" that is moderately between the extremes of conventional thinking of media as message, and post-modernist thinking about texts as contexts of behavior, Sato views information -- to use my metaphors rather than his -- as not merely a passive flow of data into the brain, but as a dynamic script which enables the brain to think and act differently. So Tomizawa's book, in following this "birth of news" view of information and nishikie, secures his niche in the world of early modern media studies. Its main interest to us is the concluding chapters, in which he extends the semantic range of "jiji nishikie" (current events nishikie) to include "shinbun nishikie" (news nishikie) and "nishikie shinbun" (nishikie news) -- thus linking his late Edo work with the early Meiji work of Tsuchiya Reiko, whose views of news nishikie he accepts without much question. In fact, the publisher of this book, Bunsei Shoin, is also the publisher of Tsuchiya's CD-ROM (2000), the current bible of news nishikie studies, which this book in some sense complements. ContentsNishikie no chikara includes the following chapters.

|

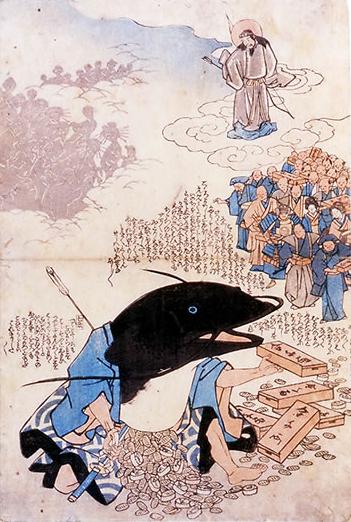

KuniyoshiTomizawa introduces the satirical work of Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798-1861), partly to set the historical stage -- since Kuniyoshi survived the Tenpo Reforms of the 1840s, during which certain officials attempted to censor the sort of political lampoons that he and many thrived on. Kuniyoshi is also a reasonable starting point for Tomizawa's story because it was mostly his disciples who, inspired by his sense of humor, drew the catfish prints that fill nearly sixty pages at the heart of the book. The chapter on Kuniyoshi opens with a large black-and-white image of a "shinie" (death picture) memorializing the master, drawn by his principle student, Yoshiiku, and published by Hiroko [Hirooka Kosuke], in 1861. Yoshiiku and Hirooka were among the founders of Tokyo nichinichi shinbun in 1872. Yoshiiku started drawing the news nishikie that bore the name of this paper in 1874. Gusokuya was the principal publisher of this seris, but Hiroko published one of Yoshiiku's Taiwan expedition triptychs bearing the same banner. The chapter on the emergence of "current events nishikie" is an overview of both the history of scholarship on the "journalismization" of nishikie, and kawaraban with news-related texts and illutrations. |

Catfish picturesLegend has it that a huge catfish in the earth causes eathquakes. A keystone (kanameishi) resting on the head of the catfish somewhat prevents it from thrashing around. Daimyojin, a diety at Kashima shrine where the keystone comes to the surface of the earth, must push down on the stone in order to pin and totally immobilize the catfish. This legend enjoyed a revival after the Ansei earthquake of 1855. Hundreds of pictures were published showing catfish, often personified, as objects of pacification or extermination. Some prints show Kashima Daimyojin pressing the kanameshi down on the head of the catfish so it won't shake the earth. Many show the catfish being attacked and subdued by mobs of people, harpooned, or cut opened and broiled as kabayaki, the way eels are eaten. One print shows a catfish at the feet of a sumo wrestler with the graphs for "kanameshi" on his head. Another features Fire and Catfish grappling as sumo wrestlers. Another print, belong to a sub-genre having to do with the impact of earthquakes on personal wealth, depicts a catfish committing seppuku. "The catfish is apologizing for the damage it has caused the world through earthquakes, and compensates by spewing gold coins from its belly" (No. 15 pages 78, 112). Measles picturesUnlike most scholarly books in Japan, this one has a very nice index -- after which comes a 23-page appendix featuring small images and texts of the 84 measles pictures listed in a table in Chapter 5. In terms of total pages, then, measles nishikie are the dominant topic of the book. The vast majority of the drawers of the measles prints listed in the table were students of Kuniyoshi -- Yoshitora (14 prints), Yoshimori (14), Yoshifuji (9), Yoshitsuya (8), Yoshiiku (7), Yoshitoshi (4), Yoshimune (4), and so fourth. Practically all the prints have approval seals (aratamein), and the seals are for either the 4th or 7th month of Bunkyu 2 (1862). News nishikieIn the unnumbered final chapter, Tomizawa introduces a few nishikie which depict incidents in the last years of the Edo period. Included is an early 1868 print by Hiroshige showing children at play -- representing the parties that been feuding in the Boshin wars. Then he jumps to the appearance of newspapers and the first "shinbun nishikie" (news nishikie) series -- Tokyo nichinichi shinbun (TNS) drawn by Yoshiiku and published by Gosokuya, and Yubin hochi shinbun (YHS) drawn by Yoshitoshi and published by Kinshodo. From this point onward he is bascially following Tsuchiya Reiko. Tomizawa repeats Tsuchiya's views about news nishikie in Osaka as being really "nishikie shinbun" (nishikie news) rather than "shinbun nishikie" (news nishikie). He accepts, without critical examination, her argument that nishikie served as conveyors of "news" in Osaka before there were newspapers -- while in fact her own evidence testifies that, even in Osaka, "nishikie shinbun" were subjected to regulation and suppressed because they were viewed as something other than real "news". The only full-page image in the book, other than the color frontispiece, is a black-and-white image of TNS Number 445 showing an old tanuki ("raccoon dog") who had turned into a three-eyed monster (p 160). There is no explanation as to why this print, which was published some thirteen months after the story appeared in the newspaper and has little "news" value, constitutes an example of the "current events" quality of news nishikie. "Journalismization" ended before news nishikieThere is something deeply ironic about Tomizawa's assumption that news nishikie represent a later stage in the "journalismization" of nishikie. For late Edo "current events nishikie" -- the catfish, measles, and early Boshin war prints published in 1855, 1862, and 1868 or thereabouts -- appear to have been more timely and urgent than anything produced in the mid 1870s. Unlike the news nishikie, the late Edo prints stood pretty much alone as sources of information (including humor) about current events. And the "news" they conveyed appears to have been more timely and even more vital than the stories retold in news nishikie. Many of the TNS and YHS news nishikie appeared months, even years after the original reports in their namesake papers. And regugitated stories about murders, suicides, births of triplets, appearances of ghosts, or marital disputes in remote prefectures had less entropy (information value) than stories which sought to alleviate anxiety (even through humor) about the possibility of more earthquakes or outbreaks of measles in one's home town. In other words, there is a huge discontinuity between the development of nishikie as conveyors of news in the 1850s and 1860s -- and the advent of news nishikie as essentially "news souvenirs" in the mid 1870s. One can even argue that the true "journalismization of nishikie" began and ended before the appearance of news nishikie -- that kawaban and nishikie passed the "news" baton on to late Edo and early Meiji newspapers -- and that "news nishikie" are mostly examples of what I would call the "nishikieization of journalism" to echo Suzuki Jin'ichi -- or, to call a spade a spade, the "souvenirization of news". |

Danjuro VIII's suicideIchikawa Danjuro VII (1791-1859) was banished from Edo during the Tenpo Reforms, leaving his son, Danjuro VIII (1823-1854), to support the family of actors. Danjuro VIII was known to have prayed for his fathers amnesty at Naritasan, and that such a filial son should kill himself a few years after his father was allowed to return to the stage added to the public's (and his father's) shock. According to a contemporary account, Danjuro VIII committed jigai on the 6th day of the 8th month of the 7th year of Kaei (27 September 1854) at age 32 (Tomizawa 2005:56-57 and Note 26, citing the final volume of "Kogai zeisetsu" [Superfluous commentary on talk about town], a 7-volume collection of gossip about things that happened in Edo between 1791 and 1857, compiled by Jinsai Okina, about whom nothing is known). Assuming that "age 32" counts as one year the time Danjuro VIII lived in his mother's womb, he lived in the world outside for 31 years and some months. The term "jigai" was one of the most common expressions for suicide at the time. Literally "self-wound" or "self-injure", it could mean anything from cutting one's throat to seppuku -- most likely the former in the case of Danjuro VIII. A 1917 source observers that Danjuro VIII's death inspired over two-hundred nishikie, many of them shinie (Tomizawa 2005:57 and Note 27). Tomozawa categoried the Danjuro VIII shinie he observed in the collections of several Tokyo libraries as follows. categorizes the shinie in as follows as follows (Ibid. 57).

This, Tomizawa said, "was not just tsuizen [a pursuit of good by the those living in this world to pacify the demons that would harm the those who have gone on to the next world, but something written irresponsibly about the cause of Danjuro VIII's death . . . ." Most were hastily produced, without the names of their drawers, or of their publishers, who rarely took the time to obtain approval from the authorities. (Ibid. 57-58) Library marketNishikie no chikara is priced for the reference book market supported mainly by libraries and specialists. As a bound volume it is very well made, sturdy enough to withstand the heaviest abuse. Tomizawa's Nyuusu no tanjo presentation is superior aesthetically, but then Nishikie no chikara makes no pretensions of being an exhibition catalog. Mutilators will find only one color plate to tear out -- the frontispiece, showing a picture of Ichikawa Danjuro VIII (1823-1854), whose suicide in Osaka in 1854 set off an avalanche of memorial prints (see below). The edition being reviewed is described as a second printing published on 25 March 2005. Amazon.co.jp states that the book was published in Feburary 2004. And the "New Acquisitions in History of Art" listing of UC Berkeley Library for April 2005 states that a copy with a 2004 publication date was accessioned into the East Asian Library in Durant Hall, home of the East Asian Languages Department. The call number is NE1321.8.T66 -- in case you are on campus and want to squint at the hundreds of tiny black-and-white images with your reading glass of choice. Durant Hall, built a century ago on a campus founded in 1868, the watershed between the Edo and Meiji periods, has been retrofitted to withstand the sort of earthquakes that constantly threaten the San Francisco Bay Area. Nonetheless, EAL staff would be advised to place a suitably sanctified figure of Kashima Daimyojin in the stacks, just in case the hundreds of catfish in Tomizawa's book become restless. I would guess there are more catfish in Tomizawa's book than in the polluted marsh near my home. Its waters are getting clearer, though, which might explain the two earthquakes I felt while reading the book and writing this review. Or perhaps the quakes are a premonition of the divine retribution that awaits me for being so perverse in my criticism. (WW) |

Tsuji Nobuo (compiler) A very entertaining introduction to ukiyoe in the daily lives of people of the Edo period. Not an academic book, but intended to instruct and delight. Well illustrated in color and black-and-white. Most of the text consists of tutorial captions which point out specific elements of prints. Unlike a lot of ukiyoe guides which focus on the high and elegant, this book gives equal space to all genres, including muzan'e and shunga. A four-page spread on news nishikie characterizes the prints as Meiji equivalents of today's tabloidesque weeklies that feature scandalous photographs and stories. (WW) |

Uchida Keiichi Forthcoming. (WW) |

Uemura Masuro and Takamizawa Tadao Vol. 1. Suiko / Tenpyo / Fujiwara This early-Showa set of boxed oversize books presents works of art depicting some degree of nudity from early historical eras through the Taisho and early-Showa periods. Each volume presents about 100 plates, most in black and white on thick non-glossy paper, some in color on glossy paper, with commentary facing each print plate on thinner interspersing leaves. Volume 5, which covers the Meiji period, is of interest because it includes three news nishikie among 86 plates. The first plate is a beautiful woodblock-printed, hand-tilted, tissue-protected miniature reproduction of a Kunisada II triptych of bathing women. The next twelve plates are in color, and the first monochrome plate is YHS-532, one of the most spectacular prints in this series.

The comments on all three prints are by the lithographer, woodblock artist, printmaker, and poet Oda Kazuma (1882-1956). Oda writes this about news nishikie in his introduction to early-Meiji nude drawings (pp 10-11).

I cite this to show both (1) how easy it was for even people as close to the subject of woodblock art as Oda to err in particulars like dates (1872, rather than 1874 and 1875) and purpose (newspaper supplements or illustrations, rather than stand-alone prints), and (2) how practicing artists like Oda viewed news nishikie from the perspective of ukiyoe as art. Oda's attitude toward news nishikie was both equivocal and ambivalent -- equivocal because he couldn't just accept or dismiss them -- ambivalent because he saw they had some artistic merit. Oda didn't think much of the design of the human figures in YHS-532, but he found the colors and composition very ornate and dramatic. The "erotic and grotesque touches [mi]" of the picture, showing a naked girl being rescued, would appeal to the "fads of the present", he wrote, alluding to the popularity of "ero-guro" themes in late-Taisho and early-Showa Japan. Late-Taisho and early-Showa interest in news nishikie was mostly shown by students of journalism and popular culture like Ono Hideo and Miyatake Gaikotsu. However, it is clear from this volume on nudity in Meiji art that they were also of interest to artists cum critics like Oda, who focused on their artistic forms rather than their social functions. (WW) |

Unno Hiroshi This book has no relevance at all to the subject of ukiyoe or news nishikie. It is shown here only because of the use of Suzuki Harunobu's "Jumping Beauty" print, oddly reversed, on the cover. It is actually a collection of short historical fiction on a variety of aspects of life in the Edo period. The collection won the 4th Saito Ryoku'u Prize in 1995. Ryoku'u (1867-1904), whose life spanned the Meiji period, was a writer of historical fiction. (WW) |

Yamada Nanako This book by Yamada Nanako render's Helen Merritt's and Yamada's 2000 English work, Woodblock Kuchi-e Prints (see review), all but totally obsolute for anyone able to read Japanese. The centerpiece of the book is a block of 140 pages of color plates featuring 1,045 kuchie -- of over 1,500 kuchie Yamada claims to have found, of about 2,000 that some researchers estimate were produced. The cover of the dust jacket bills "Nanako Yamada" as "Associate Member / Center of East Asian Studies / University of Chicago" -- as though the publishers felt they needed to boost the status of the author in the eyes of readers who might otherwise balk at shelling out 8,500 yen for the privilege of owning the best book in any language on the subject of kuchie. The book contains the following sections. 4 pages of color plates 3 pages of index 1-231 Main text [232] Guide to color plates 233-372 Color plates 373-374 Afterword 375-381 Index 394-383 English summary The text is attracitvely printed on cream acid-free paper. The 7 color plates in front, and the 1,045 color plates in back, are printed on non-coated white acid-free paper. The signatures are very securely sewn between very sturdy boards in a spine that will never break. The English summary presents a reasonable overview of kuchie as a form of story illustration in books and magazines. English-bound readers will want to keep their copy of Merritt and Yamada 2000, but know that this Japanese update is now the authority. Readers of English and Japanese alike need to keep in mind that Yamada restricts her definition of "kuchie" to colored woodblock prints that appeared mostly as frontispieces in literary magazines during the late Meiji and early Taisho periods. In the real world, the term "kuchie" refers to any illustration that appears at the front of a magazine or book -- including black and white photographs and lithographs. (WW) |

| Publishers |

| Matsuki Heikichi |

3

Kikan Uiyoe The seasonal journal Ukiyoe has occasionally carried articles on woodblock print publishers, who controlled the entire process, from conception to production and sales. Drawers and carvers, as well as printers, were essentially hired hands. Of interest in this issue, celebrating the 100th year of the Meiji Restoration, is the second feature on the Matsuki Taihei family of publishers. The family was closely associated with the career of Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847-1915), one of the last major drawers of the Meiji era. See Daikokusha Matsuki Heikichi for an article on the anthropology of this publishing family based on this issue of Ukiyoe among other sources. |

| Drawers |

| Kuniyoshi |

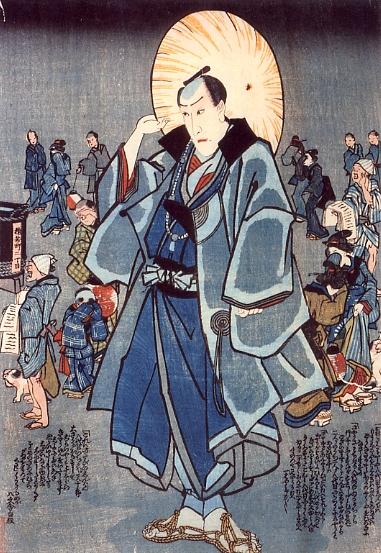

Geijutsu Shincho This issue of Geijutsu Shincho features one of the better overviews of the life and work of Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798-1861), the most important woodblock picture drawer of the 19th century, bar none. Numerous mostly color plates show Kuniyoshi's unrivaled breadth talent to draw anything and everything, from orthodox and revolutionary to folksy and erotic. He left nothing to the imagination as he drew everything imaginable. His attitude toward the human condition -- beauty, absurdity, violence, authority -- was contagious among his disciples -- Kawanabe Kyosai, Ochiai Yoshiiku, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, many others -- who kept his torch lit and passed it on. (WW) |

| Ekin |

Chikamori Toshio Gruesome and bizarre pictures designed for their shock value have a long history in Japan. One Edo-period artist who contributed to this genre, and who remains very popular, was "Ekin" (1812-1879), who was born Kinzo (few commoners had family names before the Meiji period), the son of a hairdresser in Tosa, now Kochi prefecture. As a youth, Kinzo was skilled in graphic arts, and was apprenticed to a master of the Kano school of art named Ikezoe Yoshimasa, taking the name of Yoshitaka. At his master's recommendation in 1829, at age 16, he was sponsored by the Tosa domain to travel to Edo, where he studied under the master Soke Tohaku, an "artist laureate" appointed by the Tokugawa Shogunate to supply it with art. In addition Kinzo received instruction in the style of the Kano master Maemura Towa. In 1832, Kinzo returned to Tosa and arranged to obtain samurai status, which could be purchased via a sponsor. He changed his name to Hayashi Toi and became a painter under the patronage of a senior Tosa official, a highly prestigious and desirable position. He was later accused of producing forgeries and ignominiously dismissed. Kinzo's activities over the next 10 years remain unknown. He is believed to have wandered through Tosa province, subsisting on earnings as a dye artist, producing banners and fabrics. In any case, none of his works from this period remain. The period coincided with the Tenpo Reforms, in which "frivolous" forms of popular culture were suppressed by Mizuno Tadakuni, a senior official to the Shogun. After Mizuno was dismissed in 1843, kabuki made a comeback. Kinzo, now "Ekin" (literally "picture gold"), resurfaced and began to paint "shibaie" (illustrations of dramatic scenes). Many of these works, which remain from the 1840s and 1850s, are gruesome and bizarre, showing bloody brawls, decapitated heads, and other violent scenes from famous kabuki dramas, sketched to achieve maximum shock value. Whether or not such pictures brought more customers to the theaters, Ekin's drawings, depicting graphic violence, won him immortality. His shibaie were reproduced on paper folding screens and paper lanterns. They were even kept by people as a charm against evil spirits. Who would have thought that Ekin, who had trained in one of the most orthodox schools of art, would have gained fame for lowbrow works appealing to the hoi polloi? Even today, he remains a figurehead in his home prefecture of Kochi, which holds an Ekin Festival each July. This small book, with over 40 prints and sketches, half in color, is a nice introduction to the life and work of this most unconventional artist. (MS) |

| Kawanabe Kyosai |