|

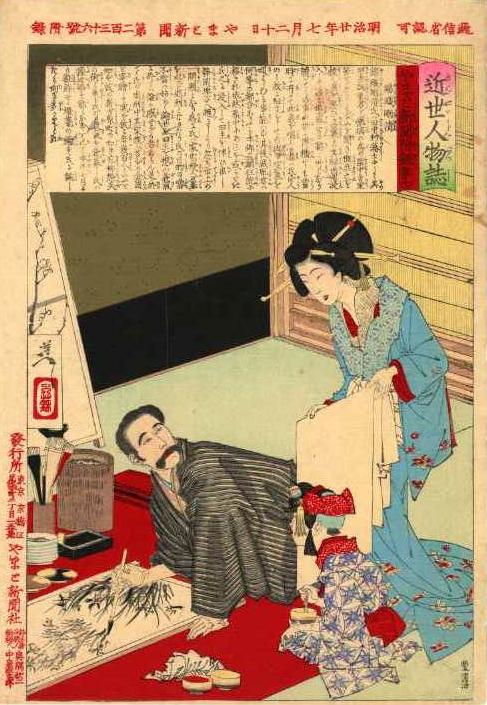

Nishigori brushing picture

Yosha Bunko

|

|

|

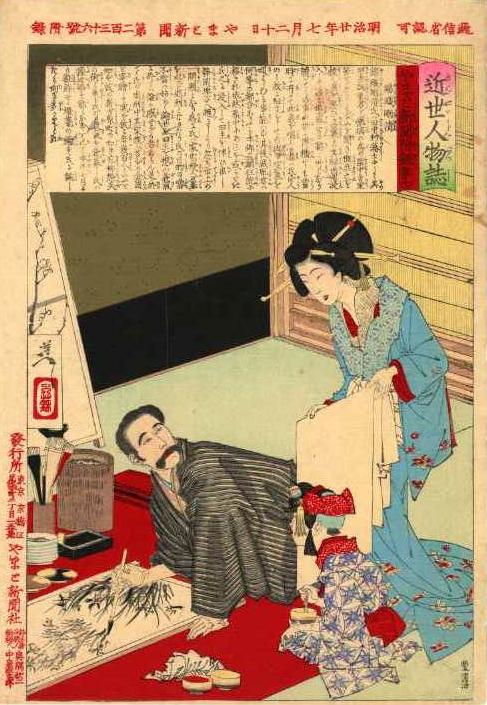

Nishigori rescuing Soma from asylum

Copped from Hara Shobo

|

|

Kinsei Jinbutsu Shi

Yamato Shinbun Furoku No. 10

Nishigori Takekiyo

Among the thousands of boring prints of kabuki actors, warriors, courtesans, loyal wives and assorted weirdos, it is refreshing to see a different sort of hero -- a man who went to court to free his former lord from a mental institution where the police had confined him in 1883. The lawsuit began in 1887, shortly before Yoshitoshi drew this picture of the Meiji-style loyal samurai. The litigation continued until 1895, three years after Yoshitoshi's -- and the former lord's -- death.

The incident became the subject of a play called "Ai nishiki gonichibanashi" [Soma brocade sequel]. In 1893, Toyohara Kunichika (1835-1900) drew a triptych of a scene from a current production. The picture shows Nishigori Takekiyo rescuing his master Soma Tomotane (1852-1892) from Sugamo Tenkyoin (Sugamo insane asylum). Kokunimasa (1864-1912) drew a similar triptych the same year.

The Soma Incident

Susan Burns, at the University of Texas, has studied the Soma Incident "as a set of reactions to the new understanding of 'madness' authorized by the formation of the psychiatric discipline, the institution of the asylum, and the regime of public health." Here is the abstract to a paper she presented on this subject at the 1997 Annual Meeting of the Association for Asian Studies (Burns 1997).

From 1883 to 1895 Japanese newspapers were filled with reports of the "Soma Incident." At the center of this controversy was Soma Tomotane, the last daimyo of Nakamura-han, who at the age of twenty-five was diagnosed as insane by the most prominent physicians of Meiji Japan and confined by his family, first in their Tokyo mansion, later in the new public and private asylums of Japan's capital. The plight of Soma Tomotane became public when, in 1887, a former retainer named Nishigori Takekiyo went to court charging that Soma was being unlawfully confined. For the next eight years, Nishigori attempted to prove that the charges of madness were a ruse concocted by members of the Soma family who, with the aid of the medical establishment, the police, and the courts, were trying to gain control of the family fortune. Nishigori lost his legal battle and was convicted of libel, but he won in the battle for public opinion. His account of the Soma saga went through seventeen printings in 1892 and it was followed by more than twenty other books, all of which portrayed Tomotane as a tragic hero and Nishigori as a loyal vassal.

Psychiatric Examination

Soma was the daimyo of Nakamura domain in Mutsu province, now Aomori prefecture, from 1865-1871. In 1887, to accommodate the prosecution in Nishigori's lawsuit, he spent 41 days (10 March to 19 April) at an Imperial University Medical College hospital for examination. The diagnosis, confirming his insanity, was written by Sakaki Hajime (1857-1897), fresh back from his studies under the German neurologist Karl Friedrich Otto Westphal (1833-1890) and others. Sakaki certified that Soma suffered from spontaneous mania (jihatsusei sobokyo).

Concurring with this opinion was the German doctor Erwin von Baeltz (1849-1913), a professor of physiology and an internist at Tokyo Imperial Medical College from 1876 to 1902. He was not employed the year of August 1892 to July 1893, when he became involved in the Soma case. Baeltz promoted the preservation of martial arts but is best known for his contributions to hot springs therapy, hence the "Baeltz Onsen Center" at Kusatsu in Gunma prefecture. The good doctor treated the rough skin of a maid at an offspring with a glycerin and potash solution that became marketed as "Baeltz water".

Soma died of heart failure in 1892 at what had by then become Tokyo-fu Tenkyoin (Tokyo prefecture insane asylum). The following year, on the basis of a claim by Nishigori that Soma had been poisoned, Soma's body was disinterred from his grave at Aoyama Bochi. An army physician examined the heart and stomach but did not confirm Nishigori's suspicions. Detailed reports of the disinterment were carried in Hochi shinbun (1893-9-14) and other papers.

Enter Goto Shinpei

On 25 October 1893, authorities searched the home of Goto Shinpei (1857-1929) in connection with the Soma Incident. Goto, a physician, embarked on a career as a medical bureaucrat and politician after treating Itagaki Taisuke (1837-1919) when Itagaki was stabbed in an assassination attempt in 1882. Itagaki, a Tosa samurai, had helped overthrow of the Tokugawa shogunate then pushed for representative government to prevent domination by former Satsuma and Choshu clansmen.

Undoubtedly with Itagaki's influence, Goto joined the Home Affairs Ministry and was sent to Germany to study. Back in Japan, he served two stints -- 1890 to 1892 and 1895 to 1898 -- as chief of the ministry's Sanitation Bureau, the precursor of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, now reunited with the Ministry of Labor (both ministries evolved from bureaus under the Home Affairs Ministry). His home was searched between these stints.

The police needed an imperial sanction to arrest a high-ranking official like Goto, but eventually, on 16 November, he was taken into custody by Tokyo police officers while walking in Kanda. The hearings in Nishigori's libel case didn't begin until 12 February the following year, but Goto, who apparently had backed Nishigori, was found innocent for reasons of insufficient evidence.

In 1898, Goto was sent to Formosa as a civil administrator to assist Governor General Kodama Gentaro (1852-1907). Goto was essentially a welfare carrot to Kodama's more military stick. Kodama is credited with finally quelling Taiwanese resistance to Japanese rule, while Goto bought Taiwanese cooperation by establishing a medical school and health facilities. Goto tried to understand and administer the people on their own terms, hence his promotion of the earliest large-scale studies of indigenous Taiwanese by Japanese anthropologists.

Impact on Mental Health Laws

The most important legacy of the Soma Incident, however, is its role as a precedent in forensic psychiatry, and its impact on legislation like the Mentally-ill Persons Protection Law (Seishinbyosha hogo ho) of 1900 (Law No. 38) and the Mental Illness Asylum Law (Seishin byoin ho) of 1919 (Law No. 25). Nishikawa Kaoru at Niigata University has recently dug up the incident and performed a post-mortem to determine its relationship to the 1900 law (Nishikawa 2003).

|