Harmonics

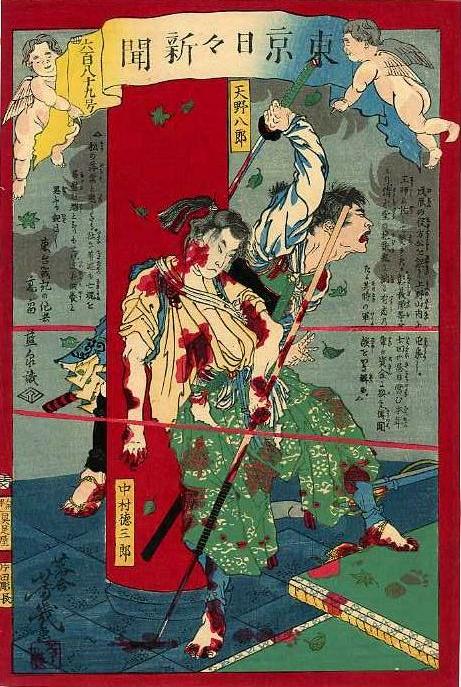

Reading this deceptively simple story is somewhat like hearing a pure fundamental which lacks the complex harmonics that give natural sounds their tone quality or color. Here, Takabatake is a minimalist who knows his readers will come up with the harmonics and resonate if all he writes are the fundamentals. They will recognize the two heroes Yoshiiku has named Amano Hachiro and Nakamura Tokusaburo. They will clearly recall the tension that had gripped Edo seven years earlier, in the weeks after the arrival of the revolutionary forces that had defeated the Tokugawa army in Osaka and sent the last Shogun packing to Mito. They will know that, despite the relative peace which has come under the Meiji government, the civil wars are not quite over, and tensions over Taiwan continue with China.

Many people would already have read about observances of the 7th memorial year of the Shogitai in a broadsheet or other publication. Some might even have read Takabatake's story in the 16 May 1874 edition of Tokyo nichinichi shinbun (Issue 689), five months before the publication of this print by Yoshiiku in October (TNS-689). A month earlier, in the 9 April 1874 edition of the broadsheet (Issue 656), they would have read about the harsh suppression of a rebellion in remote Saga, which resulted in the execution of Eto Shinpei, the former Minsitry of Justice (TNS-656). And in the 10 May edition (Issue 687), they would have read a story about the widow of another executed Saga rebel who lost her will to live and took her child with with her (TNS-687).

In other news that spring and summer, they would have heard that thousands of Japanese troops had shipped to Taiwan on a punitive expedition. In the 10 June 1874 edition (Issue 712), a month after reading about the Shogitai memorial, they would have read about the fierce battle at Stonegate in which a number of Taiwanese natives and Japanese soldiers were killed (TNS-712). And in the 14 November edition (Issue 851), they would be reading that foreign wars, too, leave grief- and guilt-stricken kin, and otherwise give birth to restless ghosts (TNS-851).

The news nishikie retellings of these stories came from weeks to months after they appeared in the broadsheets. No matter that someone who bought a print might not have read the story in a newspaper or heard the story from someone. No one could not have been aware that the world was changing rapidly, and the threat of death, from one cause or another, was never far away.

The vicarious experience of war, and its violence, might not have been as dramatic as a live feed from an embattled neighborhood in Iraq, or a camcorder document of a ride-along with cops on a drug beat, but heat is relative. News nishikie don't stand a chance beside today's "hot" media. You could watch two or three days of live invasion and terrorism in the time it took a drawer, writer, copyists, carvers, and printers to publish a single news nishikie. But those single drawings must have equally resonated with their beholders, if only for a minute or two, as they were passed around a family circle or group of friends, or read over the shoulder of someone.

Fallen pine needles

Takabatake Ransen signed more of Yoshiiku's Tonichi nishikie than any other writer. However, he usually signed Tentendo Shujin or Tentendo Dondon when writing stories for woodblock prints. This is the only news nishikie on which he used his more common gesaku by-line. And he did so because he was writing a very personal story.

Takabatake was in fact one of the concerned parties who profited from the 7th anniversary memorial. In May that year, he and a writer named Maeda Natsushige had published a book they entitled Todai senki (東台戦記) or "Eastern Heights war chronicle" but also called Matsu no ochiba (松廼落葉) or "Fallen leaves of pines".

The above publication particulars are noted in a web-posted study of Tatabatake Ransen by Takagi Gen, a University of Chiba professor who specializes in Edo and Early Meiji literature. See Sources below.)

The work was woodblock published in two volumes, which contain some woodcuts and color maps. Waseda University Library has a, and high-quality scans of its pages are available on the library's website.

Maeda was the son of Maeda Natsukage, a scholar of national literature (kokugakusha) who was close to the Tokugawa family. He was also a student of national literature, from which he became a writer, and a contemporary of the "last Shogun" Tokugawa Yoshinobu (1837-1913), who was disposed by a coalition of pro-imperial (or at least anti-Tokugawa) forces.

See more about Maeda's career in Saigoku senso nisshi: A chronicle of disturbances heralding Seinan War.

Maeda (1841-1916) was 72 in Meiji 45 (1912), the date inscribed on a memorial stele at Hikawa Jinja in Sagamihara city, commemorating the development of new rice paddies in Sagami province in 1856 by a wealthy Oyama village farmer named Hara Seihee Mitsuyasu. Yoshinobu is credited with the calligraphy on the stele, while the selection of the incribed words is attributed to Maeda. Hikawa Shrine is the Seishin area of Sagamihara, between Sagamihara station and the Oyama area of the city. "Seishin" is a compound of "sei" in the name "Seihee" and "shin" in "shinden", a reduction of "Seihee shinden" or "Seihee's news paddies". The area is dotted with schools and shops with "Shinsei" or "Oyama" in their names.

The point is not that history lives on the surface or barely below it. Rather it is that Takabatake was associated with a man who had good reason to sympathize with the Tokugawa family in general and with the deposed last Shogun in particular. And here he is, writing a story for a news nishikie that (1) not only expresses his own sympathies with the Shogitai heroes portrayed by Yoshiiku in their final moments of valience, but (2) also includes a thinly veiled advertisement for a book he admits to have coauthored with the intent of capitlizing on the grief of a local battle that is still very fresh in everyone's memory.

The "Todai" (東台) in one name given the book by Maeda and Takabatake survives as "Taito" (台東) in the present name of the ward that includes Ueno Park. It derives from the fact that Ueno Hills rose to the east of the Edo capital and was geographically ideal as a site for complex of temples that served as both a retreat for the Tokugawa family and a spiritual shield for the city.

Yoshinobu was the "last Shogun" to whom some members of the Shogitai had vowed to remain loyal unto death. After turning Edo castle over to the restorationists, Yoshinobu had taken refuge in Daijiin, within the grounds of Kan'eiji, which was on Ueno Hills. Shortly after this he retired to Mito, leaving behind a group of Tokugawa defenders that styled themselves Shogitai (彰義隊, illuminate justice regiment).

Fukuzawa Yukichi

Since 1957, Keio University has celebrated May 15 as Francis Wayland Day. This is a rather unseasonal remembrance of the day Fukuzawa Yukichi (1835-1901), a Bizen province (now part of Oita prefecture) samurai turned linguistic cum educator, began lecturing at his new boarding school in Edo, shortly to become Tokyo, using as his text "The Elements of Political Economy" by the American Baptist clergyman and educator Francis Wayland (1796-1865), an early president of Brown University (1827-1855).

The date is unseasonal for the same reason most historical events are celebrated out of sync with history in Japan today. After the government adopted the solar calendar from 1 January 1873 (the 3rd day of 12th month of the previous lunar year), people simply began marking lunar months and days on the solar calendar. The confusion is amplied by translators, including not a few scolars, who forget to convert lunar dates to their true solar equivalents.

The events which occurred on "May 15" actually took place on the 15th day of the 5th month of the 4th year of Keio, a lunar calendar date that translates into 4 July 1868.

On the morning of this early summer day, in the midst and mist of a warm seasonal rain, government forces commenced their anticipated attack on Sogitai forces entrenced at Ueno Hills (Uenoyama), now the famous park, then the Buddhist sanctuary of the Tokugawa clan, intended to protect their political interests in Edo from demons to the north. By evening, the Sogitai had been routed, many killed, others talking flight, some to melt into the new order, a few to join remnants of anti-government resistence in places like Aizu-Wakamatsu. Some 1200 houses had been burned in the course of the fighting.

While the Battle of Ueno was raging, Fukuzawa Yukichi gave his first lecture at his new Keio Gijuku boarding school in the Shinsenza in Shiba, now part of Hamamatsu-cho 1-chome in Minako-ku. According to Fukuzawa's memoirs, translated into English by his only grandson, Eiichi Kiyooka (清岡瑛一), he and his students were able to hear the shooting, probably the firing and explosions of cannon shot, as fire from muskets might not have been audible at that distance in the rain.

This is how Fukuzawa remembers the Battle of Ueno Hills in his autobiography (Fukuzawa 1972:209-210).

It was our good fortune that the school in Shinsenza was not burned in the combat of the Restoration. By and by our classrooms and the details of administration were somewhat organized, but affairs in society around us were far from peaceful. In May of the first year of Meiji (1868) [In July of the last year of Keio (1868)], there occurred the fierce battle of Ueno. A few days before and after this event, all theaters and restaurants and places of amusement were closed, and everything was in such a topsy-turvy condition that the whole city of "Eight Hundred and Eight Streets" seemed in utter desolation. But the work of my school went right on.

On the very day of the battle, I was giving lectures on economics, using an English text book. Ueno was over five miles away, and no matter how hot the fighting grew, there was no danger of stray bullets reaching us. Once in a while, when the noise of the streets grew louder, my pupils would amuse themselves by bringing out a ladder and climbing up on the roof to gaze at the smoke overhanging the attack. I recall that it was a long battle, lasting from about noon until after dark. But with no connection between us and the scene of action, we had no fear at all.

Thus we remained calm, and found that in the world, large as it was, there were othermen than those engaged in warfare, for even during the Ueno siege and during the subsequent campaigns in the northern provinces, students steadily increased in Keio-gijuku.

Fukuzawa's autobiography was first published in Japanese in 1899. Kiyooka's translation was first published in 1934, not long after he had published an article called "Across the United States in a Model T Ford" (1927). The above (revised) translation was first published in 1960.

Commentary (Andon 80)

Reading this story is like hearing a pure fundamental which lacks the harmonics that give natural sounds their tonal qualities or colours. Takabatake knew that those who saw this nishikie would resonate with his narrative.

They would recognise the names in the two cartouches -- Amano Hachirō (1831-1868) and Nakamura Tokusaburō. They would recall the tensions that had gripped Edo in the days leading up to the battle at Ueno, just weeks after the arrival of the coalition of samurai who had defeated the Tokugawa army in Kyoto, sent the last shogun packing to Mito, and started a new government sanctioned by the emperor. They would have known that, despite the peace that had come with the start of the Meiji era, the civil wars were not quite over. And there were reports of battles in Taiwan, wherever that was.

Some would have been among the throngs of well-wishers at Ueno on 15 May 1874. Or the following day they may have read in Tōnichi about the groups that had offered funds to "condole the spirits under the [yellow] springs (senka / izumi no shita) [underground world of the dead]". First listed was the Kishōza in Hamachō, which contributed 25 yen in gold. This kabuki theatre, built just the year before, was the forerunner of the Meijiza in Nihonbashi Hamachō in Chūō ward today.

The Tōnichi article went on to note that Takabatake Ransen and Maeda Natsushige had been seen at Ueno on the 15th. They had written an "unusual book" called Matsu no ochiba [Fallen leaves of Pines], or Tōdai senki [Eastern heights war chronicle], of stories about the heroes. The writers had brought together their hands at the [memorial] service [in thanks] that they "had already received permission and publication was near."

Many people, still reckoning time according to the lunar calendar, officially abandoned after 1872, would have recalled that the battle of Ueno hills did not occur on "15 May" but on the morning of the 15th day of the fifth month of the fourth year of Keiō, or Boshin, a lunar calendar date corresponding to 4 July 1868 on the solar calendar.

On the morning of this early summer day, in the mist of a warm seasonal rain, government forces commenced firing on holdouts at Ueno. What is now the park was then the Buddhist sanctuary of the Tokugawa clan, built to protect their political interests in Edo castle from demons to the northeast.

By evening, the Shōgitai and others had been routed. Many were killed, and those not downed by bullets took flight. Some melted into the new order. A few joined remnants of resisters in places like Aizu-Wakamatsu. Amano was captured and died in jail that December. Many of the temples and about 1,200 homes in the area were burned.

Fukuzawa Yukichi (1835-1901), a Bizen province samurai turned linguist-cum-educator, recalled that while the battle was raging he was giving his first lecture at his new Keiō Gijuku boarding school, now Keiō University. He remembered hearing the cannon fire, and that some of his students had climbed onto the roof and gazed at the smoke.

Since 1957, Keiō University has somewhat unseasonably celebrated 15 May as Francis Wayland Day. For on that bloody morning of 1868, Fukuzawa and his students were reading The Elements of Political Economy by the American Baptist clergyman and educator Francis Wayland (1796-1865), an early president of Brown University.

[Commentary from Wetherall and Schreiber 2006 in Andon 80]

Principal sources

Takabatake Ransen

Takagi Gen refers to, and cites in detail from, TNS-689 in the following biographical study of Takabatake Ransen (page 436).

Takagi Gen

Takabatake Ransen no jidai

[Takabatake Ransen's era]

Pages 431-453 in

Hino Tatsuo, Nakano Mitsutoshi, Kobayashi Isamu, Takagi Gen (compilers)

Kaika fūzokushi shū

[Civilization (Enlightenment) manners-and-customs journals anthology]

Shin Nihon koten bungaku taikei (SNKBT)

[New Survey of classical literature of Japan]

Meiji-hen 1

[Meiji compilation No. 1]

Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2004

451 pages, hard cover, boxed

For a web version of Takagi's article on Takabatake's life, and other features related to "minor stories" (shōsetsu) in 19th-century Japan, see Takagi's website, Fumikura (Text Archives).

For more about Takabatake Ransen as a writer, see also TNS-689 Shogitai heroes and TNS-876 Mysterious incidents on this website.

Fukuzawa Yukichi

Fukuzawa's grandson, Kiyooka Eiichi, published an English translation of his grandfather's autobiography (1899) in 1934. The 1960 revision has a foreword by Carmen Blacker.

The Autobiography of Yukichi Fukuzawa

Revised Translation by Eiichi Kiyooka

With a Foreword by Carmen Blacker

New York: Schocken Books, 1899, 1934, 1960

xxiii, 407 pages, softcover

For more about Fukuzawa and other sources related to his work and life, see "Fukuzawa Yukichi on 'martyrdom'" in TNS-860 Nanko and Gonsuke on this website.