Commentary

For another story about a husband who sends his wife packing with her lover, and his blessings, see TNS-940a Man ousts wife and lover.

The following commentary is from Wetherall and Schreiber 2006 in Andon 80.

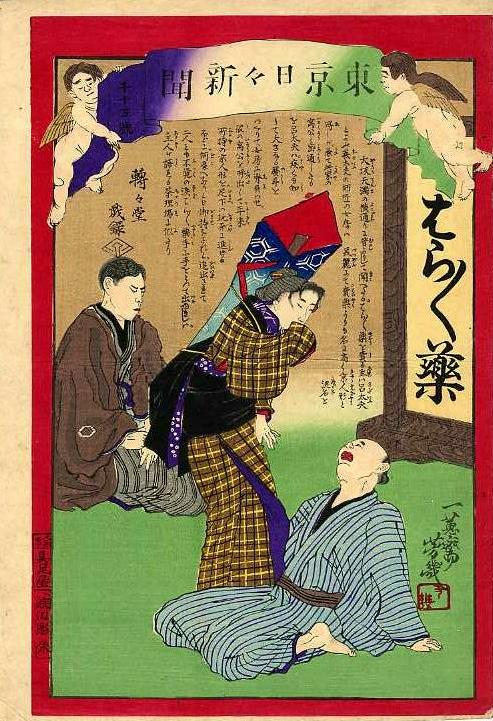

She was twenty two or three according to the original Tōnichi article. As the big sign in the drawing says, Rodayū was a seller of haraharagusuri, a popular remedy for all manner of gastrointestinal discomforts -- still made and sold today in Osaka. Anatomically "hara" means stomach or abdomen -- while "harahara" is an onomatopoeic expression for feelings of unease and fear, or for the sounds of burning or fanning, or of falling leaves, dew or tears, among similar conditions -- hence the wordplay at the end.

Rodayū was the husband's stage name as a performer of jōruri -- epic ballads narrated on stage to the accompaniment of a string instrument. Tentendō uses gidayū, the Kansai term for jōruri, to rhyme with the husband's name. Performing gidayū became Rodayū's principal occupation. His wife's beauty made her more famous than the remedy handed down in his family.

As Rodayū is presenting a guest in his home with a gift, he speaks to his wife's lover in terse but polite terms. The tension thus built is released with their eviction and tears -- which become the butt of two wordplays, one involving the name of the medicine, the other the unexpected (fukaku no) turn of their indiscretion (fukaku).

Tentendō turned an ordinary newspaper account into a playful story suitable for oration -- told in 19 couplets divided into 12 segments translated here as 9. His own telling of the story has echoes of the chariba, or comical jōruri, that Rodayū might have told on stage.

Shinbun zue (News illustrated), a news nishikie published in Osaka, featured the same story in its No. 38 issue. Unlike other prints in this series, No. 38 has no publisher, drawer, carver, or writer signatures. Its story is attributed to "Tōkyō nichinichi shinbun" and follows the newspaper account very closely. Its illustration shows a woman with noshi attached to her back, and a man with a cartouche reading Rodayū.

The noshi in both drawings is an exaggerated version of the kind of small ornament that would have been attached to practically any gift formally given to congratulate or wish well. A typical noshi was made of strips of dried abalone that had been flattened and stretched to represent the spread and continuation of fortune. The strips were often wrapped in colourful papers as shown in the drawings. Today noshi are mostly printed images on paper attached to seasonal gifts, or on paper wraps or envelopes used to give money at weddings or graduations.