Fish . . . birds.

From the Confucian Analects (C. Lunyu, J. Rongo), Chapter 7. The original is 子釣面不網、弋不射宿 or "The master fished but not with a net; he shot a bow but not at birds at rest." Tentendo writes 釣 (つり) して網 (あミ) せず宿鳥 (ねとり) を射 (い) ず (Tsuri shite ami sezu netori o izu), which partly translates and partly interprets the original.

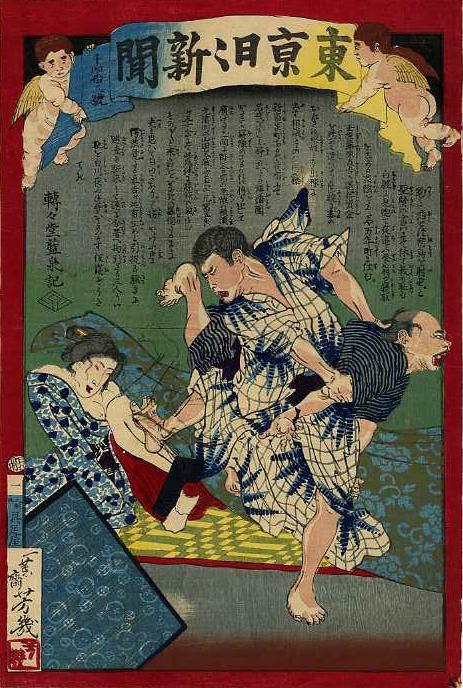

Tentendo then writes 宿取(ねとり)をしめる姦淫(かんいん) (netori o shimeru kan'in), or "fornication in which one wrings the neck of a cuckold" -- where "cuckold" (netori) is a pun for "resting bird" (netori). The cockold "netori" means "to take (someone's wife) at rest". Expressions like "tori / niwatori o shimeru" mean to "wring a bird's / chicken's neck".

Tentendo contrived all this just to make puns on "shooting a sleeping bird" and "taking another man's sleeping wife". He didn't become a "gesakusha" (writer of vulgar works) for nothing.

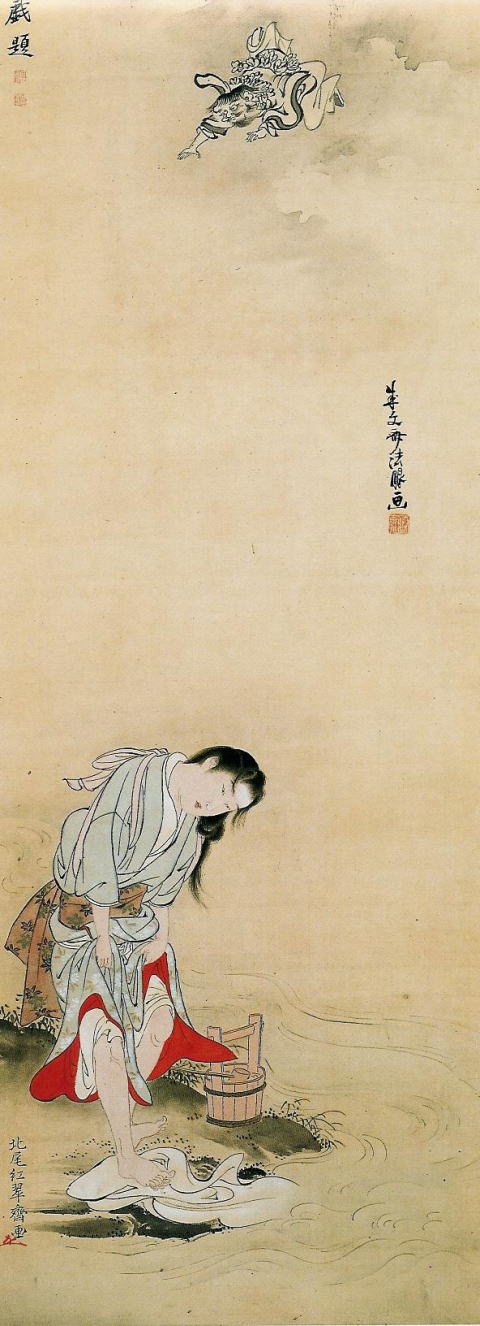

Kume no SenninTentendo writes 粂翁 with the furigana gloss せんにん (sennin). This is a good example of how hybridized Japanese had become by the mid-19th century. The first character 粂 is a "kokuji" created in Japan to represent the name Kume (久米) in a single graph. The second character 翁 (C. weng, J. ou), a true "kanji" meaning older man or father, is suffixed in Chinese and Japanese kanbun to the names of venerated older men. So 粂翁 is a kanbunesque form of 久米の仙人 (Kume no sennin), a semi-legendary figure who appears in classical works like Konjaku monogatari (Book 11:24), a 12th-century collection of Buddhist parables, and Tsuregurekusa (Essay 8), a collection of random thoughts about life by Yoshida Kenko (1283-1352). Tentendo's mention of Kume no probably alludes to Yoshida's essay, which begins by observing that"Of things that confuse the hearts of people in this world, none is tantamount to the desire for color" (世の人の心まどはす事、色欲にはしかず) -- "color" being an allusion to sexual love. Yoshida then relates how "The mountain ascetic Kume saw the whiteness of the legs of a woman who was washing [clothes] and lost his [magic] power" (久米の仙人の、物洗ふ女の脛の白きを見て、通を失ひけむは). Kume is supposed to have been able to fly, and seeing the woman's bare legs, he fell to the earth. Kume's fall is the subject of at least one hanging scroll, and possibly another scroll and a folding screen. Shown here is part of a scroll in the Museum fur Kunst und Gwerbe in Hamburg. The image was copped from a scan that was copped from Hirayama Ikuo and Kobayashi Tadashi (editors), Hizo Nihon bijutsu taikan, Volume 12, Yooroppa shuzo Nihon bijutsu sen, Tokyo: Kodansha, 1994, 289 pages hardcover. The scroll was drawn in the 1780s by Kitao Shigemasa (1739-1820). It depicts the Konjanku monogatari parable of Kume no Sennin, which relates that the woman is washing her clothes in the Yoshino river when Kume spots her. Kume is said to have worked hard to redeem himself, regained his powers, and built a temple -- or inspired the building of a temple, putatively Kumedera in Kashihara city, Nara prefecture, which dates back to the time of Shotoku Taishi (574-622). The scroll would easily qualify as a picture in the Thematic Apperception Test. Christians would blame Kume for being unable to resist temptation. Muslims would blame the woman for tempting Kume. Buddhists would blame the illusions of sentiment and write it off as fate. |

ex-samurai

Tentendo refers to Fujiwara Naoyoshi as a shizoku. This was a legal status had only recently originated. It conferred on him the prestige of having once been a member of a military family (buke) under Tokugawa law. It might have given him cause for pride, but it also meant he no longer enjoyed the privileges of the abolished buke caste. It also stimatized him as a possible loser.

The Nationalization of the Domains

Of all the changes that took place during the Meiji period, the most important was the nationalization of the territories and populations of the feudal. This meant two things: (1) the domains (han) "returned" (hokan) their registers of land and people (hanseki) to the emperor (hanseki hokan), making both part of the new nation; and (2) the social castes that had been defined under the feudal order were reclassified into castes that were thought to be more suitable for the population of an imperial state (shimin byodo).

More specifically, the domains were abolished and became prefectures of the imperial state, while the people became nationals of the state and subjects of the emperor -- meaning they now owed their allegiance to the state and the emperor, not a domain and daimyo.

The Recasting of Castes

The formal restructuring of social castes took place between 1869 and 1872, but the repercussions are still felt today, as some people still take pride in, or hide, their family's historical caste. In a nutshell, the seven or eight castes that formally defined people under Tokugawa laws were regrouped into four castes.

| koshitsu | imperial family -- members of the imperial household |

| kazoku | titled nobility -- mostly former court nobles and daimyo |

| shizoku | ex-samurai -- mostly from the more influential military families (buke) that had immediately served a daimyo or the court |

| heimin | commoners -- consisting of lower-ranking or quasi-samurai, farmers, craftsmen, merchants, and people who had once been classified as eta or hinin outcastes |

And Then There Were Two

Shizoku status was no longer recorded from 1914, the under the new Constitution of 1946, and relevant laws, the kazoku caste was abolished, the imperial household was reduced to the emperor and his immediate family -- the consequences of which are now apparent as the family faces extinction.

Under the Meiji Constitution of 1889 and relevant laws, Japanese nationals were shinmin or "loyal subjects" of a sovereign emperor. Today they are kokumin or "the people" in which the constitution invests sovereignty. Since 1899, qualifications for nationality have been stipulated in the Nationality Law.

Today there are only two castes of Japanese: (1) members of the imperial family, and (2) all other nationals. Nationals are all people who legally qualify for inclusion in a family register, including the family register of the imperial household.

General family registers and the imperial family register define two castes because they are governed by different laws which differentiate the two kinds of registers by lineage. Unlike general families in Japan, which are corporate and not strictly based on birth, succession within the imperial family is strictly a matter of patrilineal descent

Ironically, the laws that govern the imperial family treat its members as second-class citizens. Under the guise of an exclusive and indelible status, they do not enjoy the freedoms that are guaranteed members of general family registers.

Shitaya Mannencho

A part of Edo and early Tokyo, in the vicinity of present-day Kita-Ueno-1 and Higashi-Ueno-4 in Taito-ku.

severance stipend

Tentendo writes "kanroku shikin" (還禄資金) but glosses it "hokankin" (ほうくわんきん). Both refer to funds that many samurai received, in the form of a payment or loan to start a business or otherwise invest and survive, after nationalization of the domains, when they lost their jobs and hereditary entitlements as samurai. I have coined "severance stipend" as a generic description of all forms of such compensation.

Token Compensation

When the domains were disenfranchised, samurai retainers were dispossessed of their hereditary privileges, which included stipends of rice. The rice was allocated as payment for their services. The daimyo became prefectural governors and received titles of nobility. The services of especially influential samurai continued to be needed in local, prefectural, and national governments, as they were essentially bureaucrats. But most ordinary samurai found themselves out of work and not particularly employable.

Many samurai, when dispossessed, received a token payment or loan that was intended to compensate them for their lost privileges and help them restart their lives. Unfortunately, many samurai had no idea how to survive outside the cozy world of special privilege.

Samurai Business Nonsense

Most shizoku struggled. Even Fukuchi Gen'ichiro had to struggle. Well-educated, well-connected, well-traveled, and by reputation a very hard worker -- Fukuchi had to struggle to make a living and was hard pressed for cash when he started Koko shinbun in 1868.

But for every Fukuchi Gen'ichiro, there was a Fujiwara Naoyoshi.

So common were stories of ex-samurai who had fallen on hard times that the term expression "shizoku no shoho" [the commercial code of ex-samurai] was coined to describe a business venture that was doomed to fail because it was undertaken by someone who had no business sense.

Restless Warriors

The first decade of the Meiji period witnessed a considerable amount of social unrest. Some of this unrest culminated in riots, armed insurrections, and outright civil wars.

The most violent reactions to social change were fueled by the discontent of disenfranchised samurai. As many as three million suddenly found themselves unemployed.

Some shizoku took advantage of opportunities to resettle in places like Hokkaido, which the government wanted to develop. Others tried their hand at farming, manufacturing, or business. Some succeeded, some didn't. Some simply could not imagine a life that did not involve their warrior skills, no matter how symbolic.

In Kyushu domains like Satsuma and Saga, which had led the overthrow of the Tokugawa shogunate, an explosive mix of economic frustrations and nationalist sentiments festered in shizoku militias that sought an outlet -- in 1873 in Korea (proposal rejected by the government), then in 1874 in Saga (brutally suppressed by government military forces), again in 1874 in Taiwan (accepted, then rejected, then tacitly accepted by the government), and next in 1877 in Satsuma (again, brutally suppressed by government military forces).

The Saga and Satsuma rebellions of 1874 and 1877 were predictable, given the conditions that were brewing throughout the country, but particularly in Kyushu, where the call to subjugate Korea was strongest, and the punitive expedition to Taiwan was assembled and led. By the late 1870s and early 1880s, the government finally undertook measures to relieve some of the debts of failed shizoku.

Two Shizoku, Two Fates

Fukuchi Gen'ichiro and Fujiwara Naoyoshi were among the majority of shizoku who did not seem to miss their swords. Most likely they never wore them except on ceremonial occasions.

Ironically, the names of both men are immortal because they did something unusual to get attention, one positive, the other negative. Fukuchi became one of the most influential opinionists of the Meiji period. Fujiwara beat up the man he caught drawing an arrow on his sleeping wife, and maybe her too.

Tentendo might have cut Fujiwara some moral slack if all he had done was come to his wife's defense. Most likely, though, he was also coming to the defense of what little he had left of his shizoku honor. Having blown his loan, and taken her to Naito Shinjuku with the thought of putting her to work in one of its dives, he had nothing left to blow but his temper.

Tentendo was right. Awakened from a samurai dream indeed!

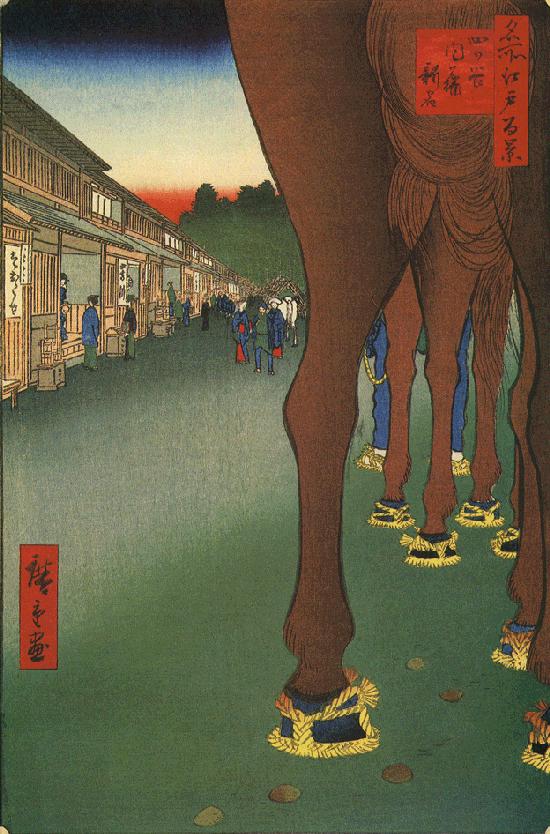

Naito ShinjukuNaito Shinjuku was built on part of the land that was given to Naito Kiyonari (1555-1608) by Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616), the first shogun of the Tokugawa period. The land was strategically important because it included the first stretch of the only escape route out of the castle, and Kiyonari had been one of Ieyasu's most trusted allies. The escape route was Koshukaido, which ran from Nihonbashi to Kofu (and eventually to Shimosuwa on the Nakasendo) by way of Hachioji. The road approached Edo from the west and ran to Yotsuya Mitsuke, the guard station on the outer moat of Edo castle. From there one could go directly to the castle through Hanzomon on the inner moat, or skirt the outer moat to Nihonbashi. Shinjuku was created on Naito clan land along the Koshukaido in 1698 (Genroku 11), hence the name Naito Shinjuku. The motives behind its creation were essentially economic, and the means of its creation were essentially political -- as are most new developments. Leaving Edo on Koshukaido, the first accommodation stop was Takaidojuku, near Shimo-Takaido stations on Keio and Tokyu Setagaya lines in present-day Suginami-ku. This was a long way to travel in one day, however, so a certain entrepreneur who had connections with the Yoshiwara entertainment quarter in Asakusa paid the Tokugawa shogunate a considerable amount of money for a license to open a new (shin) rest stop (shuku, juku) with lodging and other services for travelers. The site chosen for the new stop belonged to the daimyo of Naito, who was required to give the shogunate some land as part of the deal. (Haga Zenjiro, Shinjuku no konseki, Tokyo: Kinokuniya Shoten, 1970, page 38, as referred to in Sugimoto Akiko, "Meshimori onna and the politics of prostitution", 2001). Naito "new town" had shops, horses, and places for exchanging money. It also had tea houses and inns called hatago. "The hatago served two purposes. They were not only inns for travelers but also brothels. The hatago were constructed under bakufu license, but their quality was much lower than that of Yoshiwara establishments." (Ibid, Sugimoto 2001) Shinjuku Gyoen National Garden, in Naito-cho of present-day Shinjuku-ku, also sits on what was once part of the Naito estate. The Meiji government built the Naito Shinjuku Experimental Station on the site in 1872. The facility moved to Komaba in 1877 and became Komaba Agricultural School, later the agricultural department of Tokyo University. The Imperial Household Ministry, which took over the site from the Home Affairs Ministry, redeveloped it into the Shinjuku Imperial Botanical Garden in 1879. An entirely new garden, redesigned for the use of the imperial family and called the Shinjuku Imperial Garden, was completed in 1906. The garden was opened to the public with its present name after World War II. Naito Shinjuku has come a long way from its origins as a horse stop. Thanks to all those people in the Tokugawa and Meiji periods who were interested in the development of the travel industry, prostitution, and agriculture, we have the congestion and openness, the cacophony and tranquility that constitute Shinjuku today. The woodblock print is "Yotsuya Naito Shinjuku" by Ando Hiroshige (1797-1858). It is No. 86 of the Meisho Edo hyakkei (One hundred famous views of Edo) series, which he drew the last two years of his life. The road apples in the foreground prove two things. You had to watch your step in Shinjuku then as much as now. And Hiroshige was a naturalist, though in putting the apples in the foreground, immediately below the trees from which they fell, he was flirting with realism. |

shirakawa yofune

The title of the Japanese edition of Yoshimoto Banana's Asleep is Shirakawa Yofune. The original English edition also went by this title. For sure the romanization means nothing to someone who doesn't know its meaning in Japanese. And just as certainly, something is lost in translation.

The expression alludes to the story of a man who claimed he had been to Kyoto. Someone asked him how he liked Shirakawa, one of the more famous sites in the imperial capital. Thinking Shirakawa was a river, the man says he doesn't know because he traveled on a night boat. He'd slept and hadn't seen a thing.

So the expression alludes to a plea of ignorance about an incident on the grounds that one was asleep. But it also alludes to the transparency of such an excuse as a lie.