Commentary

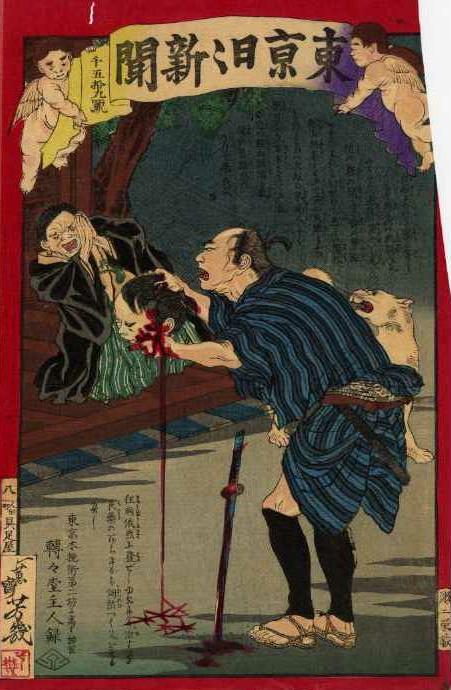

This print opens windows on numerous elements of life and language in early Meiji Japan. The Yosha Bunko copy appears to have gotten in the way of the sword of a madman attacking one of its previous owners for collecting such detritus.

No medicine for fools

there being nothing equivalent to medicine for a fool reflects 白痴(ばか)につける薬(くすり)と等(ひと)しくさて無(ない)ものハ or "baka ni tsukeru kusuri to hitoshiku sate nai mono ha [wa]". This alludes to the saying "baka ni tsukeru kursuri wa nai" (馬鹿に付ける薬はない), meaning "there is no medicine for [to cure] a fool [idiot, imbecile] [for foolishness, idiocy, imbecility]".

白痴 would be read "hakuchi" in Sino-Japanese, but is here marked to be read "baka", which is usually graphed 馬鹿. Both refer to someone who lacks native intelligence.

"Hakuchi" (白痴) was once used as the medical term for "idiot" or "idiocy" as the severest degree of mental retardation. Today the term is considered discriminatory.

However, "baka" (馬鹿) -- idiot, imbecile, moron, dunce, fool -- is very commonly used today, most often lightly, to chide someone -- especially a family member, friend, classmate, spouse -- for being or acting, or doing something, crazy, dumb, stupid, or silly.

decoction translates 湯液(くすり) graphically. The Sino-Japanese reading would be "tōeki", though the graphs are commonly read "yueki" -- a mixed Japanese and Sino-Japanese reading. Here the graphs are marked to be read "kusuri" (薬) -- the more general word for "medicine" -- of which a "decoction" or "infusion" made by boiling roots or leaves is but one kind.

maniac is graphed 風顛(きちがひ)人 (kichigahi > kichigai hito). 風顛 was a simpler way of writing 風顚 -- a popular form of 瘋癲. These graphs, which would be read "fūten" in Sino-Japanese, are here marked to be read "kichigai" (気違い、気狂い)-- a Japanese word a person of "different temperament" -- an insane or crazy person, a lunatic, madman, screwball, nutcase, et cetera.

However, 風顛 (瘋癲) is also as a play on 風天 (fūten) -- the God of the Wind in Indic myth (Sanskrit Vāyu) -- hence a derelict or vagabond -- a person who wanders with the wind, roofless and workless. Tora-san of movie fame is affectionately called "Fūten no Tora-sa" (風天の寅さん).

Today "fūten" written 風顛 (瘋癲) is virtually extinct -- while "kichigai", though still alive, is scheduled for extinction as it appears on most lists of discriminatory expressions to be avoided in public intercourse and mass media.

The expression 瘋癲白痴 (fūten hakuchi) is sometimes used to refer to both classes of people. In present-day parlance, the former would be a person with a mental illness, the latter someone with a low IQ.

madness in the closing translates 狂病(きやうひやう) (kiyauhiyau > kyōbyō), which graphically means "mad-malady" -- craziness, insanity.

good drug in the closing represents 良薬, which would be read "ryōyaku" in Sino-Japanese in reference to an effective medicine. Here the graphs are marked to be read くすり (薬) -- again, the most general Japanese term for "medicine".

Tokaido

Fukuroi (袋井) and Mitsuke (見附) were adjacent stations on the Tōkaidoō (東海道) traveling from Edo or Tokyo in the direction of Kyoto and Osaka. The station after Mitsuke was Hamamatsu (浜松), the castle town of the former Ōtōmi domain. These are now the cities of Fukuroi (袋井市), Iwata (磐田市), and Hamamatsu (浜松市).

Hamamatsu prefecture (浜松県) was formed from Ōtōmi domain (遠江国 Ootoumi no kuni) in 1871 when neighboring Suruga domain (駿河国 Suruga no kuni) became Shizuoka prefecture. Hamamatsu prefecture and part of Ashigara prefecture were merged into Shizuoka prefecture in 1876.

stations represents 驛(しゆく) (shiyuku > shuku), a graph read "eki" in Japanese but here marked with the Sino-Japanese reading of 宿 -- which, if read "yado" in Japanese would mean mean "lodging", but here means 宿駅 (shukueki) or 宿場 (shukuba), i.e., a post town or stage.

Why the incident took place where it did is not clear. The story implies that the rice dealer and shizoku were members of Osaka and Hamamatsu family registers, and possibly the "chief of registers" had jurisdiction of the shizoku's register, but neither inference is certain. And the story remains silent as to whether the shizoku had once been in Osaka, or whether the rice dealer was residing in Hamamatsu.

Shizoku

shizoku (士族) was the largely face-saving status given numerous lower-ranking former samurai when their domains were "returned" to the emperor and they lost their positions as retainers. Those unable to gain posts as officials in the new prefectural and local governments were given a small severance payment, with which they were expected to start a business or otherwise fend for themselves.

Shizoku continued to be a caste until 1886. Notations of shizoku status in family registers were discontinued from 1914. In 1948 all notations of such inheritated lineage (zokuseki) titles were struck from family registers.

For more about shizoku as a newly defined caste, see class, caste, outcaste in the Minorities Almanac section of the Glossaries feature of the Yosha Research website, and Social status laws in Japan: Caste, class, and titles of nobility since 1868 in the Law section of the Society feature of the Yosha Research site.

head with cut-hair, dripping fresh blood reflects 腥血(なまち)淋漓(したた)る散髪(さんばつ)の首級(くび) (namachi shitataru sanpatsu no kubi). Apparently the shizoku had cropped his hair in the manner that had become fashionable after 1871, when men whose status had obliged them to wear topknots and swords were free to cut their hair and not wear swords, thus ending such distinctions in dress.

It is not clear from the story whether the Osaka rice dealer actually had a personal reason to carry out a vendetta against the Hamamatsu shizoku, or whether he simply went crazy and attacked the shizoku as a target of opportunity. Nor is it clear whether the shizoku was bearing a sword at the time, as had divested himself of his sword as an affectation of his former samuari status when, if not before, he cut his hair.

The sword in the drawing appears to be a long sword, which a rice dealer would not usually have been allowed to carry -- though some non-samurai carried shorter swords, and a few non-samurai were known to dress like and pass themselves off as samurai. It is even possible that the shizoku was killed with his own sword. In any event, the drawing depicts only what Yoshiiku saw in his imagination.

The wearing of swords, other than by military and police officers, and certain other people on ceremonial occasions, was not generally prohibitted until the following year. For details, see Meiji sword, hair, and clothing laws in the Law section of the Society feature of the Yosha Research website.

Petty officials as writers

Petty official residing on 2nd block of Kobikichō in Tokyo reflects 東京木挽街第二坊に寓す稗宦 -- which would be read Tōkyō (Tōkei) Kobikimachi (Kobikigai, Kobikichō) Dai-ni-bō haikan.

Tentendō Shujin (Takabatake Ransen) actually resided at "1st large district, 15th small district, Kobikichō 2-chome 5 banchi" (第一大区十五小区木挽町二丁目五番地) in Tokyo prefecture (東京府) -- hence the significance of 第二坊 (Dai-ni-bō), though 坊 (bō machi), referring to a Chinese-style administration area of a capitol city, is more likely used in reference to Kyoto.

稗宦 (haikwan, haikan) was usually written 稗官 (haikwan, haikan). But 宦 (kwan, kan) can also mean an official who has been castrated -- a so-called "eunuch" -- i.e., 宦官 (kwangwan, kangan). Hence Tentendō is possibly stylizing himself as a "petty enuch" residing in the heart of the capitol prefecture -- Kobiki being in the Ginza area.

稗 (hai, hie) means "millet" -- regarded as an inferior grain -- hence its use in a number of compounds mean "minor" or "petty", as in 稗史 (haishi), meaning stories about ordinary people written by the petty officials who oversaw their lives -- otherwise known as "minor stories" (小説 shōsetsu).

Tentendō refers to himself as a writer of "minor stories" in his by-line on TNS-9001, TNS-1036a, and TNS-1054. For more about "minor stories" with reference to Tentendō (Takabatake) as an author of popular fiction, see "Minor stories" and style: The essence of "shōsetsu" and news nishikie.