|

|

Kanshiro hirome tebikae (cover)

|

|

|

Kanshiro hirome tebikae (title page)

|

Kanshiro hirome tebikae No. 1

Kanshiro information notes

完四郎広目手控

Kanshirō hirome tebikae

[Kanshiro information notes]

Shosetsu Subaru: May 1997 to May 1998

Hardcover: August 1998, 317 pages

Bunko: December 2001, 347 pages

This premier volume of the Koya Kanshiro series develops the hero's life and character through twelve episodes set during the years that the United States is pressuring Japan to open ports to provision American ships and accommodate trade.

Kanshiro, a disenfranchised samurai too young and lacking in social status, has to survive on his native wits and charm. In need of a vocation, the fictional Kanshiro becomes an information broker through the device of crossing paths with two historical figures -- Fujiokaya Yoshizo, who made his living collecting and disseminating information, and Kanagaki Robun, a writer of frivolous stories and journalist who also traded in information.

See Fujiokaya Yoshizo below for more about this historical figure.

See Kanagaki Robun's Aguranabe: Beef, sake, news, and Westophiles in Early Meiji Japan in the Articles section for more about Kanagaki Robun and a partial translation of the opening story in his "Ushiya zodan aguranabe" collection.

The twelve stories in this collection are partly inspired by Ando Hiroshige's "One hundred scenes of famous places in Edo" (名所江戸百景 Meisho Edo hyakkei). Published between 1856 and 1858, the series includes about 118 prints. Hiroshige, born in 1797, died in 1858.

Blurb on cover band

|

The streets of Edo, during the Ansei years [circa 1855-1860], immediately after the coming of Perry's black ships. Fujiokaya Yoshizo, engaged in the business of a "hiromeya" [information broker], which was like what today would be called an advertising agency. [This book] is a new series, which has portrayed the activities of the outlaws of Edo, to which it has added the free-loading plain [ordinary, nobody-of-a] ronin Koya Kanshiro, and also Kanagaki Robun and others. The author states he got ideas from Hiroshige's "One hundred scenes of famous places in Edo", and accordingly the landscapes of Edo of the Edo period are nostalgic, [in this collection of stories, which] is an amateur detective incident book of Kanshiro and others, who go about solving, with brilliant reasoning and inquiry, incomprehensible incidents that, reflecting the times, occur one after another.

|

|

Top

|

|

Tengugoroshi (cover)

|

|

|

Tengugoroshi (title page)

|

Kanshiro hirome tebikae No. 2

Tengu killings

天狗殺し

Tengugoroshi

[Tengu killings]

Shosetsu Subaru: December 1998 to January 2000

Hardcover: June 2000, 300 pages

Bunko: December 2003, 327 pages

The twelve stories in this second collection in the Kanshiro series are partly inspired by Hiroshige's "Fifty-three stations of the Tokaido" (東海道五十三次 Tōkaidō go-jū-san tsugi). The series has 55 prints, including the starting and ending stations in Edo (Nihonbashi) and Kyoto (Sanjō Ńhashi) -- according to this definition of the route.

Blurb on cover band

|

[This is] an action tale of Koya Kanshiro, who, throwing away [forsaking] his sword, hardened his resolve to live as an information broker.

Enticed by the 53 stations drawn by Hiroshige, by way of the Tokaido, a departure for the capital in Kyoto. At Kanshiro's side, not only the Mister Kanagaki Robun we know, but Okaori a female doctor, and the swordsman Sakamoto Ryoma of Tosa. When three actors [pros] like these come together, whatever happens will not be unthinkable [surprising].

In these times, of today serving the emperor and tomorrow saving the [Tokugawa] government, [they] go about solving the difficult cases that await them wherever they go . . . .

|

|

|

Top

|

|

Ijin yurei (cover)

|

|

|

Ijin yurei (title page)

|

Kanshiro hirome tebikae No. 3

Alien apparitions

いじん幽霊

Ijin yūrei

[Alien apparitions]

Shosetsu Subaru, March 2002 to September 2003

Hardcover: December 2003, 316 pages

Bunko: December 2006, 362 pages

This stories in this third volume of Kanshiro adventures are inspired by an assortment of triptychs and single prints, most of them belonging to the "foreigner drawings" (異人画 ijinga) or "Yokohama pictures" (横浜絵 Yokohamae) genres.

Blurb on cover band

|

The time, Bakumatsu. Kanshiro, who was anxious about the direction of the country, trembling [between] opening the country and expelling barbarians. Proceeding [into the future] is the porttown Yokoyama, where people from all countries are gathering.

In vigor-overflowing Yokohama, dancing into the midsts of the familar threesome of Kanshiro, Yoshizo, and Kanagaki Robun, who are putting their spirits into their publicizer work, an uproar over the haunted house in the [foreign] settlement. There seems to be something behind the rumor . . . .

A brilliant single hand [move] leads the mysterious incident, involving aliens, who were hindering [their] proceeding hand [their moves, their way], to a solution.

|

|

Top

|

|

Bunmei kaika (cover)

|

|

|

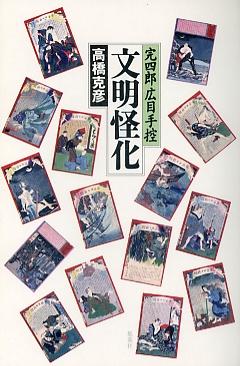

Bunmei kaika (title page)

|

Kanshiro hirome tebikae No. 4

Enlightenment and mystification

文明怪化

Bunmei kaika

[Enlightenment and mystification]

Shosetsu Subaru: March 2004 to April/May 2007

Hardcover: August 2007, 312 pages

Bunko: Forthcoming

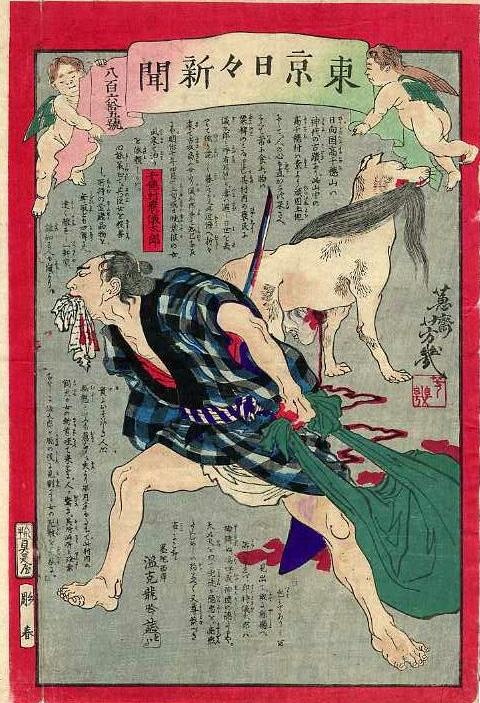

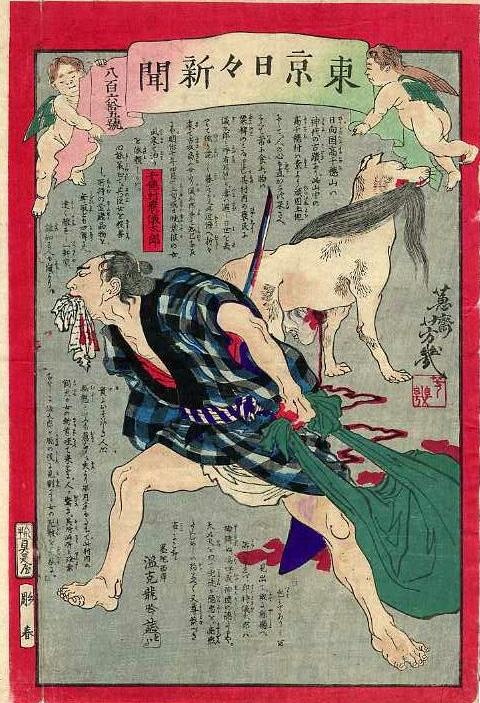

The title story of this fourth volume in the Kanshiro series is inspired by TNS-876 Mysterious incidents (click this link for full translation and commentary). The story/volume title "enlightenment and mysification" (文明怪化 bunmei kaika) -- and the line "reign of civilization and enlightement" (文明開化の御世 bunmei kaika no miyo) in the following blurb from the band of the hardcover edition -- come from the narrative on this news nishikie

|

The reign of civilization and enlightenment.

With talk-of-the-town news nishikie as handholds [clues], will the Kanshiro we know unravel and illuminate [elucidate, solve] the tomorrow of Nippon?!

Meiji 7 [1874].

Today beef pot, tomorrow Ching [Qing, Chinese] food . . . .

In front of Kanagaki Robun, who is in full fluffage [is cutting a fine figure, looking very prosperious and influential], that man [we know] returned.

News nishikie, drawn by the sketch artists Yoshiiku and Yoshitoshi, are widely reporting to society the scandalous incidents that common folk have occasioned.

The one who can seeing through this, [as] Japan creaks in the sudden changes amid the swells of the period [era] . . . .

How does Kanshiro move?

|

|

"Beef pot" in the above blurb on Volume 4 of the Kanshiro series reflects 牛鍋 (gyūnabe, ushinabe), the specialty of "beef-pot shops" (牛鍋屋 gyūnabeya) or "beef shops" (牛店 ushiya, gy#363;ten). Kanagaki Robun portrayed the fashionable ambiance of such eateries in his best known work, a collection of parodic sotries entitled "Ushiya zōdan / Aguranabe" (牛店雑談 / 安愚楽鍋) or "Beef shop small talk: Cross-legged [at a beef] pot". See Kanagaki Robun's Aguranabe in the Articles section for more about Kanagaki and a partial translation "Aguranabe".

Principal characters

Bunmei kaika differs in several respects from the first three volumes in the Kanshiro series. There was a greater gap in months before the stories destined for the fourth volume began to appear in the monthly magazine, and the stories appeared more sporadically over a longer span of months. Perhaps Takahashi was busier doing other things, or maybe he simply took more time to contrive the stories.

Most conspicuously, though, the design of the fourth volume, including the style of the blurb on the cover band, was somewhat different. Unlike the other collections, Bunmei kaika begins with a list of its principle characters (page 5, my translation).

Principal characters

|

|

Kōya Kanshirō

|

Former hatamoto retainer. In Edo, on the Tokaido, and in Yokohama during the final years of Tokugawa shogunate, while engaged in the business of an information broker [hiromeya], he solved a number of mysterious incidents [kaijiken]. He crossed to America, and a few years later returned to Japan after it had become Meiji.

|

|

Kanagaki Robun

|

Gesaku writer. Active also as a sidekick of Kanshiro. Entering Meiji he becomes an employee of Kanagawa prefecture government after entering.

|

|

Makino Shōkyoku

|

Magician from Nagasaki.

|

|

Yoshiiku

|

Drawer. Starts publishing Tokyo nichinichi shinbun [Tokyo daily news].

|

|

Yoshitoshi

|

Yoshitoshi

Drawer. Yoshiiku's junior [as] disciple [of Kuniyoshi].

|

|

Jessica

|

Girl [daughter] of different country who was living in Yokohama. Works at news company in New York, returns to Japan as correspondent (tokuhain).

|

|

Takabatake Ransen

|

Tokyo nichinichi shinbun reporter. Of samurai family origin.

|

|

Stories and associated prints

The title pages shows color thumbs of fifteen prints (13 TNS, 2 YHS). Nine stories are illustrated by one print, three stories by two prints. The stories and their prints are as follows.

Contents

|

|

1. 帰ってきた男 Kaette kita otoko [ The man who came back ]

|

|

Story features TNS-865a Dog finds head.

See partial translation of "The man who came back" (see translation of story and further commentary below).

|

|

2. 文明怪化 Bunmei kaika [ Enlightenment and mystification ]

|

|

Story features TNS-876 Mysterious incidents.

"Bunmei kaika" (文明怪化), the title story, begins like this (pages 32-33, structural translation by William Wetherall).

Enlightenment and mystification

"Even the thought never came [to me] that, early in the first month [of the new year], I'd be able to get in a bath [hotspring] at Ikaho and relax [like this]. Kansan came back too, and as for one good thing coming after another it's this. Tottyan too was shedding tears and pleased. That Kan-san would come as far as Fujioka for greetings . . . I say."

|

Ikaho (伊香保) is still a popular hotspring resort in Gunma prefecture.

Kansan (完さん) is Kanagaki Robun's friendly way of referring to Kanshiro (Kanshiro san), to whom he is speaking. When speaking face to face or writing conversationally in letters, people are as apt to use the other person's name and even their own name, or omit specification of a second or first person subject or object, than use a personal pronoun.

Tottyan (とっつゃん) -- an affectionate name for a father or a father-like older man (お父さん Otōsan) -- refers to "Fujiyoshi" or "Fujiokaya Yoshizo" -- who has recently retired and returned to the town of Fujioka (藤岡), from which he had come, hence his shop handle Fujiokaya.

Fujioka was in the province of Kozuke (上野国 Kōzuke no kuni), now Gunma prefecture. The province was broken up into nine prefectures in the summer of 1872 (Meiji 4-7-14). Three months later (Meiji 4-10-28), eight of the prefectures were merged into Gunma prefecture. Gunma was merged with Iruma prefecture and renamed Kumagaya prefecture in 1873 (Meiji 6-6-15). In 1876 (Meiji 9-8-21), Kumagaya was abolished and Gunma prefecture was recreated from the original prefecture with a few counties from Tochigi prefecture.

|

Robun, who had warmed his body in the bath, and sat his rump at the kotatsu in the room, spoke to Kanshiro, who was standing by the window and gazing at the garden illuminated by the evening sun.

"And moreover, tonight, the banquet of the Fujiyoshi family together in full force. Those days are very nostalgic. Thanks to [you guys] I became a body [person (of a status)] that has not had difficulty [making a] living, but the time I was teamed with Tottyan and Kansan [was] my flower [the best period of my life]." Recently my legs and back [body] are weak and even with just the climb of the stone steps of Ikaho my breathing rises."

Tottyan too is like that, but Oei and Oshin haven't changed a bit. I was surprised.

Kanshiro, also entering the kotatsu, smiled. The two, Oei and Oshin, are in the next room.

"The likes of women are kindrid of ghosts. Unlike the old days of Edo it's become the reign of civilization and enlightment and there are [even stories about] women becoming younger, no? When [they] passed thirty women were prepared to be drawn into the house [and no longer worry about their beauty], but now they're still in their prime. Especially when, like Oshin, in their ocean hair, you just can't tell their age."

|

kindrid reflects 縁者 (enja), meaning "related persons" -- with implications of karmic kith and kin.

ocean hair reflects 洋髪 (yōhatsu), meaning hair worn in the "western ocean" (西洋 seiyō) or "western" (European, Euroamerican) style.

|

[ The story continues as Kanagaki and Kanshiro are joined by Yoshizo. It took him less than a day to walk from Fujioka to Ikaho at the foot of Mt. Harnua. ]

|

|

|

3. 人生双六 Jinsei sugoroku [ The board game of life ]

|

|

Story features YHS-532 Officer rescues girl.

双六 (sugoroku) alludes to older board games that developed in Japan over the centuries after earlier forms entered Japan through Korea and China. 人生双六 (jinsei sugoroku) also alludes to a form of sugoroku called 人生ゲーム (Jinsei Geemu), introduced by Takara (now Takara Tomy)in 1968 as the Japanese version of the North American game called "The Game of Life" -- created in 1861 by Milton Bradley, who called it "The Checkered Game of Life".

|

|

4. 怪談指南 Kaidan shinan [ Mysterious tale instruction ]

|

|

Story features TNS-862 Married in next world.

|

|

5. びっくり箱 Bikkuri bako [ Jack-in-the-box ]

|

|

Story features two both TNS-472 Sailor writes will and TNS-322 Filial son.

|

|

6. ニッポン通信 Nippon tsūshin [ Japan wire ]

|

|

Story features both TNS-1015 Gifted wife and TNS-101 Nursing mother's spirit.

|

|

7. 絵空事 Esoragoto [ A picture is something in the air ]

|

|

Story features both TNS-933 Man murders ex-wife and TNS-833 Cop kills three women.

"Esoragoto" means that a "picture" (絵 e) is "something" (事 koto) in the "air" (空 sora) -- a figment of one's imagination. The expression comes from a story about the merits of exaggeration when drawing pictures in Kokon chomonjū. For a full translation of the story and commentary, see Kokon chomonju: "Esoragoto" and the merits of pictoral exaggeration in the Articles section of this website.

|

|

8. 死人薬 Shiningusuri [ Necromedicine ]

|

|

Story features TNS-1009 Impotent necrophiliac.

"In a graveyard on a moonlit night, a man excavates the body of a girl who had just been buried. He opens the casket. The smell of the corpse spews out. The girl's hair can be seen. The man then. . . ."

|

|

9. かどわかし Kadowakashi [ Abduction ]

|

|

Story features TNS-992.

|

|

10. 手口 Teguchi [ Modus operandi ]

|

|

Story features TNS-431 Drowing woman rescued.

|

|

11. 番茶組 Banchagumi [ Coarse tea class ]

|

|

Story features TNS-984 Husband of prostitute.

|

|

12. 幻燈国家 Gentō kokka [ Magic lantern nation ]

|

|

Story features YHS-466.

|

Top

The man who came back

First published in the March 2004 edition of Shosetsu Subaru, "The man who came back" was well conceived to lead off Volume 4 of the Kanshiro series (pages 7-30). The central characters have to be introduced to new readers, and continuing readers need to be brought up to date on developments since Volume 3.

Since Volume 3, there has been a change in governments, and Kanshiro has gone overseas. Edo has become Tokyo. Newspapers have come into vogue. Nishikie depicting the most intresting and shocking stories are circulating. These and other props vital to the background of the stories Takahashi wishes to tell need to be placed on the stage of late 1874 barely six years into the Meiji era.

And, as early as possible, Takahashi needs to provide his heroes with a mystery to solve. No better way to kick things off than with a story about a dog dragging a head of a woman whose body police find buried behind a shed in a remote village of distant Kyushu -- and a question of what really happened.

Summary of opening scenes

Kanagaki Robun, who is then 46, cross paths with a loquacious young man with a fashionable cropped head who introduces himself as Makino Shokyoku. Robun takes a liking to the man, who says he was raised as an orphan at a temple in Nagasaki. (Pages 8-13)

Shokyoku mentions that Yanagawa Chojuro will be performing London Magic at Sensoji in Ueno. Robun says he's seen the show, and was impressed by the trick in which a chicken is slaughted, blood gushing from its neck as its head falls to the stage, and brought back to life. Shokyoku says he's come to Tokyo all the way from Nagasaki precisely to see that, because he's always wanted to be a magician. (Pages 13-14)

|

Yanagawa Chōjūrō (柳川蝶十郎), or Aoki Jisaburō (青木治三郎), was a disciple of the rakugo storyteller Shunbūtei Ryūshi III (春風亭柳枝三代目 1852-1900), whose real name was Suzuki Bunkichi (文鈴木文吉).

Sensoji (浅草寺 Sensōji), sometimes called Asakusadera, is the large Kannon temple most commonly reached by domestic and foreign tourists alike through Kaminarimon (雷門) in the Asakusa neighborhood near Ueno.

|

Robun agrees that London Magic has been a great hit. People will come to see anything foreign, he says. Shokyoku attributes part of the shows popularity to coverage in Tokyo Daily News. Robun says that's because Saigiku and Yoshiiku like such things. (Page 14)

|

Tokyo Daily News reflects 東京日日新聞 (Tokyo nichinichi shinbun) -- Tokyo's first daily newspaper, which began publishing in 1872.

|

Shokyoku recognizes that Saigiku is Jono Denpei. Robun notes that Saigiku, who also goes by the name Sansantei Arindo, is an old gesakusha pal, and that Yoshiiku is a drawer, and that the two men founded Daily News. (Page 14)

|

Takahashi generally shortens the name of the paper to Tokyo Daily (東京日日 Tokyo nichinichi). Exceptionally he also calls it Daily News (日日新聞 Nichinichi shinbun) -- or perhaps he intends the latter to mean "daily newspaper" as a kind of publication.

|

Robun and Shokyoku talk for nearly two pages about Tokyo Daily in particular and newspapers of Japan generally. Their conversation dwells on the killing of some fishermen from the Ryukyu Kingdom [Okinawa] by some Taiwanese villagers, the punitive expedition that disembarked from Nagasaki to punish the villagers, Kishida Ginko's reportage of the expedition for Tokyo Daily, and the political status of Ryukyu in relation to Japan and Ching [China under Qing dynasty]. (Pages 15-16)

|

newspapers of Japan reflects 日本の新聞 (Nihon no shinbun). Here Takahashi is using 新聞 (shinbun) -- which at the time meant only "news" -- to refer to what was then called 新聞紙 (shinbunshi) -- literally "newspaper".

Another contemporary word for "newspaper" was 新聞誌 (shinbunshi) -- a vestige of the name for the "news magazines" that were published in small string-bound pamphlets or booklets. Such multiple-page newspapers appeared before the larger single-sheet broadsheets, and for a while the two formats co-existed.

|

Robun, impressed by Shokyoku's knowledge of all this, says that Saigiku and Yoshiiku might like to meet him, seeing as how he was from Nagasaki and they think Tokyo Daily is read only in the Tokyo area. Shokyoku, who plans to live in Tokyo for at least half a year, is delighted by the prospects of meeting them . . . . (Page 16)

A black-and-white image of the Tsujibun edition of TNS-865a fills page 17, and the story resumes from page 18 as follows (pages 18-22, structural translation by William Wetherall; parenthetical remarks in original; bracketed comments added).

The man who came back

|

Note on translation

The Japanese text reads more smoothly than is suggested by this structural translation, which is intended to illuminate the Japanese phrasing and wording. A somewhat freer, slightly more Anglicized English version would be as pleasureable to read as the original Japanese narrative.

The Japanese dialog contains some older expressions that lend the narrative some ambience. Robun and Shokyoku, the two characters that appear in this scene, speak somewhat differently, reflecting their different personalities, ages, and relative status.

|

[ . . . continued from above summary . . . ]

". . . Tokyo Daily's very interesting. It also puts out this, of course, no?"

Shokyoku produces a nishikie from his pocket. At a glance Robun sees that it is a news nishikie that the print producer Gusokuya of Ningyocho had published. They took as [story] material articles which had been run in Tokyo Daily and dressed [the material] in a picture; they'd been produced one after another since July and had become popular. The drawer was Yoshiiku. Gusokuya had calculated that by asking Yoshiiku to be the drawer he would get Tokyo Daily's permission.

|

nishikie reflects 錦絵 -- a multicolor woodblock print.

news nishikie reflects 新聞錦絵 (shinbun nishikie). This is the term he has used in his books and articles on such prints, following the nomenclature preferred by Ono Hideo and others, which views such prints as having been mainly souvenirs rather than newspapers -- whereas Tsuchiya Reiko and others have insisted on calling them 錦絵新聞 (nishikie shinbun), meaning either "nishikie news" or "nishikie newspapers" depending on context, arguing that such prints qualified as news media.

Significantly, Takahashi calls news nishikie simply "nishikie" -- and does not, like some writers, refer to them as "nishikie versions" or "nishikie editions" of the newspaper. This, too, is consistent with his view that news nishikie were independent productions of woodblock print publishers.

|

"That's not put out by Tokyo Daily, but, well, it's not unrelated either.

"This is just a rumor, but it seems they'll pay good money if you bring in an interesting article."

"That's true. They don't have the leeway to higher a lot of people whose main job would be to gather articles. Thirty people or thereabouts are making [the newspaper]. Everyday. They're always wanting articles to fill the paper. Write on anything that has even a little form and they'll pounce on it."

|

paper reflects 紙 -- read "kami" (most likely) if in reference to "paper" as a material, or "shi" (less likely) if in reference to "paper" as in "newspaper" (新聞紙 shinbunshi).

|

"This nishikie for example . . . "

Shokyoku pressed [Robun] to read the article part.

Robun took [the print] in hand and ran his eyes over [the article].

It is the incident of the horrible murder of a woman that occured in Takachiho village of the province of Hyoga. A farmer named Gitaro was living a solitary and lonely life. Then one night a woman with a familiar face who deals in old clothes came to ask for lodging. In the middle of the night Gitaro awakened his evil heart, and put the woman to his hands [murdered the woman] with the aim of seizing her money and possessions. As this took place in the middle of the mountains where there are no other homes in any direction, the corpse he rolled in a straw mat and threw behind a stable [outhouse]. But, half a month later. A stray dog found the corpse, tore off the head and carried it off. Villagers were startled by a dog walking around dragging a head, and when they investigated here and there, a body was found behind Gitaro's house, and [Gitaro] wound up being arrested [captured and roped] by police.

It is material perfectly suited to dressing in a picture. The situation of the dog walking around teething a fresh head [carrying a recently severed head in its mouth], and the scene of Gitaro killing the woman and hauling the corpse to the stable, are simultaenously depicted, and the design is gruesome. It was a picture that even for Robun remained in [one's] impressions. As for Yoshiiku, [his] styles [of drawing] were mostly quiet in like manner with [his] character, but in fact he is a master of brutal pictures. Eimei nijūhasshuku [Twenty-eight plebian verses about (the constellations of) glorious figures], which he produced in competition with Yoshitoshi of the same gate [a fellow student of the same teacher] during the Keio years (1865-68), gained a reputation as a peerless masterpiece all prints of which are colored by blood. Its proper province is demonstrated without laments [its true characteristics are shown to perfection]. That the news nishikie were winning a popularity approaching the newspaper of the mother house Robun saw as something due to Yoshiiku's brush.

|

brutal pictures reflects 残酷絵 (zankokue). This is a near synonym of the somewhat more common term 無惨絵 (muzan'e) -- which is also written 無残絵 but rarely 無慙絵 -- a picture depicting an act of pitiless, merciless, heartless, shameless, and unremorseful (hence "atrocious") violence.

newspaper of the mother house reflects 母屋の新聞 (moya no shinbun). I am assuming that Takahashi does not mean "news of the main house" since the topic of the sentence is nishikie and not news.

"Mother house" is a metaphor for the main building of a residence or the main room of a home, where the mistsress or master of the family would live or sleep. Here it alludes to the Tokyo nichinichi shinbun, which Takahashi has stated does not publish the nishikie but at the same times is not "unrelated" to the woodblock prints which bear its name.

|

"What about this article?"

Compared with the strikingness of the picture the article was monotonous.

"You don't think it's odd?"

"Well. In particular [no]."

"No matter that there is no lodging in the area, would a woman lightly stay at a house she knew to be [that] of a man living alone? If she was that familiar to him, his suddenly scheming to seize her money and possessions is also incomprehensible. Moreover, a corpse which had been abandoned for over half a month at the peak of summer. As for Takachiho, a heat beyond comparision with this area. I would think [the corpse] would have rotted to the point its features could not have been distinguished. Yet, do not the villagers and the police, in one day or thereabouts, step into [raid] the home of Gitaro, and discover the body from [in] the back? Ordinarly, [if] a head is found -- which firstly [no one] knows even whose it is -- [there's] going to be a huge commotion as to who it is. And that being so, [this] would have come into Gitaro's ears, and naturally he would have taken steps to hide the body. Leaving [it there] knowing [what would happen to it] and the like, an unthinkable story. Even more incomprehensible is the effortless [offhand] throwing of the corpse behind the stable. Horses are indispensible in field work. In other words, a place where Gitaro would go in and out everyday. No matter that [the corpse was in] the back, the smell would have been annoying. If there are no other homes in any direction, an argument that [the corpse] could have been buried anywhere. Different than [unlike] in the city of Yokohama where its lively and there are people's eyes. However much he may have lacked between [the ears], let's grant that [he would have had] enough [brains] to hide the body in the ground. Beyond that he was a farmer and familiar with digging the ground. Just in [this] short article this many doubts strike my eyes. Is this incident one that can really be put away [disposed of, settled, cleared] with this [article]?"

Ummm, Robun groaned, and returned his eyes to the article. At first he had seen it as not having anything incomprehensible, but looking [at it] as pointed out by Shokyoku indeed a number of uncertainties [equivalities, dubious things] could be seen. A variety of developments floated [up] in Robun's head and vanished. As for the murdered woman and Gitaro, probably [theirs] had been a cordial [close, intimate] relationship. So as soon as the head appeared the name of Gitaro floated up [surfaced, emerged]. Gitaro of course had hidden the body by burying it somewhere.

"However . . . if so, then where did the corpse come from?

Robun, twisting his head, looked at Shokyoku.

"Didn't someone dig it up and put it behind the stable?"

Shokyoku straightly [quickly, easily] replied.

"That it wasn't Gitaro is certain."

"But . . . how did the man know know the whereabouts of the corpse?" ]

"[He was] someone who got money and helped bury the corpse, or someone who together had a hand in the murder . . . since if it were revealed, the crime would extend to him as well, he just helped bury [it]."

"A dog found the head and [the man] panicked."

"That too [is questionable] . . . maybe he dug up the corpse and purposely gave the dog the head. There would be someone who, seeing the head, would immediately have mouthed that it was so-and-so who dealt in old clothes, and that person would be suspicious. And in a stroke [he] would pull the police along and head for the house of Gitaro. When the corpse was found Gitaro could not but accept [the implications]. For in the matter of [he] having murdered the woman there is not likely any mistake."

[ . . . the speculation continues . . . ]

|

|

Top

Fujiokaya Yoshizo

Fujiokaya Yoshizo (1793-187?) is an historical figure. Fujiokaya (藤岡屋) was the shop name of Sudo Yoshizo (須藤由蔵 Sudō Yoshizō), a late-Edo book book dealer and information broker.

Sudo began vending used books from a straw mat he spread alongside a stretch of Onarimichi that ran through Kanda in the vicinity of present-day Akihabara. He also recorded, daily, information that people could read for a fee. He was variously dubbed "Dharma of Onarimichi" (御成道の達磨), "Chronicle book dealer" (御記録本屋 go-kiroku hon'ya), and "Book Yoshi" (本由 Hon'yoshi), an abbreviation of "Yoshizo the book dealer" 本屋の由蔵.

Fujiokaya diaries

Sudo amassed a total of 150 volumes (巻 kan) bound in 152 fascicles (冊 satsu) in what came to be known as "Fujiokaya nikki" (藤岡屋日記) or "Fujiokaya diaries". The entries in these "diaries" span 65 years, from 1804 to 1868, and cover all manner of topics, including information and gossip about the sometimes scandalous activities of government officials.

|

|

|

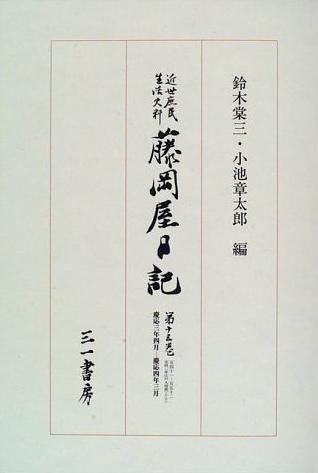

Fukiokaya nikki (Volume 15)

|

15-volume complete work

The originals diaries were lost in the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. They have been most recently published, from facsimile editions, in a 15-volume work compiled by Suzuki Tozo and Koike Shotaro.

鈴木棠三・小池章太郎 (編)

Suzuki Tozo and Koike Shotaro (compilers)

近世庶民生活史料 (藤岡屋日記)

Kinsei shomin seikatsu shiryo (Fujiokaya nikki)

[Historical materials on life of commoners life in recent <early modern> times (Fukioka diaries)]

東京:三一書房 Tokyo: San'ichi Shobo

全15巻 (15 volumes), 1987-1995

|

|

|

Fujiokayabanashi Vol. 1 (hardcover)

|

|

|

Fujiokayabanashi Vol. 2 (hardcover)

|

2-volume digest work

Because the original work is not very accessible -- each volume in the printed edition has over 600 pages and the content is not well organized -- Suzuki, a professor of Japanese literature, folklore, and oral traditions, edited selected material into two smaller volumes for the general reader.

The two volumes came out during the final two years of Suzuki's life (1911-1992), before all the volumes in the complete work had been published, and five years before Takahashi's Kanshiro stories began running in Shosetsu Subaru. They have since been re-issued in a bunko (paperback) edition -- testifying to the increased interest in such sources.

鈴木棠三 (編) Suzuki Tozo (editor)

江戸巷談:藤岡屋ばなし

Edo kōdan: Fujiokayabanashi

[Edo town talk: Fujiokaya stories]

2 volumes, Volume 2 subtitled 続集

(Zokushū:) [Sequel collection]

東京:三一書房 Tokyo: San'ichi Shobo

Volume 1: 1991, 334 pages, hardcover

Volume 2: 1992, 358 pages, hardcover

東京:筑摩書房 Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo

Volume 1: 2003, 426 pages, bunko

Volume 2: 2003, 437 pages, bunko

Onarimichi

Onarimichi (御成道) was the name a route that ran northeast from Edo castle, through the Kanda bridge gate (神田橋門 Kandabashimon) at the bridge which crossed the inner moat into the Kanda area, then through the Sujikai bridge gate (筋違橋門 Sujikaibashimon) at the Sujikai checkpoint (筋違見附 Sujikaimitsuke) at the bridge which crossed the Kanda river segment of the outer moat into Outer Kanda (外神田 Soto Kanda), the vicinity of Akihabara in Chiyoda-ku today. The route, which contunied to Ueno and eventually Nikko, was used when visiting Kan'eiji and other Tokugawa temples at Ueno and Toshogu at Nikko. "Sujikai" (筋違) designates a crossroad -- here the crossing of Onarimichi and Nakasendo (中山道).

|

Top

| |